The following includes plot details, including the film’s ending.

Netflix’s adaptation of the novel Hillbilly Elegy recently garnered criticism from critics for allegedly portraying rural Americans negatively and glorifying author J. D. Vance’s escape from poverty. The controversy began before the film’s release, as critics gave overwhelmingly negative reviews; despite this, audiences responded well to the film.

Hillbilly Elegy follows Vance as he overcomes cycles of poverty in rural Ohio to attend Yale Law School. In describing his family’s intergenerational trauma, Vance successfully analyzes the plights of rural, White, working-class Americans.

The movie begins with Vance in his second year of law school, attending interviews for summer associate opportunities. While Vance dines with his top-choice law firm, his sister (Lindsay) calls him to reveal that their mother (Bev) relapsed in her opiate addiction and started using heroin. The film follows Vance through his interviews and return home to help his mother. It features numerous flashbacks that depict how his family ended up in Ohio from Kentucky, from his grandmother (Mamaw) getting pregnant at thirteen to his mother’s abuse to the beginning of her addiction to Vance joining the Marines to escape poverty.

Hillbilly Elegy shows that people must make better choices to overcome poverty, namely in comparison to the previous generation. But the film also acknowledges that people need positive support systems to help them overcome vicious cycles. That’s why Bev and Vance’s stories turn out differently despite their similar origins. Bev was the salutatorian of her high school and put herself through nursing school as a single mother, but could not pull herself out of poverty because she did not have anyone to support her. She slips further into her addiction and struggles to raise her children. As a result, she turns to men for support, hoping that she’ll find someone who can give her family a better life.

Vance could have become like Bev; he was hanging out with the wrong crowd, drinking alcohol, and getting into legal trouble—all because he didn’t have anyone to guide him. His behavior only changes once Mamaw intervenes, as she takes custody of him and forces him to change. Vance would not have the work ethic that got him accepted to Yale Law—or even to college or the Marines—without Mamaw’s guidance and sacrifices to raise him. Mamaw prioritizes Vance’s education over her own needs, even purchasing him an $85 calculator instead of her necessary medication.

Vance’s story shows that having some kind of support system—regardless of circumstance—is critical to overcoming systemic poverty.

Despite the movie’s seemingly irrefutable message and the book’s glowing initial reception, critics rejected the film and its central themes. Notable reviews have called Hillbilly Elegy “one of the worst movies of the year” and “not the fun kind of bad,” accusing the film of seeing its characters as selective evidence that poverty is the fault of the poor.

The Atlantic’s David Simms accuses Vance and the film of mischaracterizing Appalachia. He believes Hillbilly Elegy “overcompensates for its straightforward storyline by ladling on the histrionics, such as . . . Bev’s harrowing behavior (at one point, she threatens to drive her truck into oncoming traffic with J. D. in the car).” Despite these storylines coming directly from the book and Vance’s life, Simms believes that these “histrionics” are exaggerated and have no broader purpose, leading me to wonder whether we watched the same film.

Vulture’s Alison Willmore is more explicit about her distaste for the movie’s message. Despite recognizing that “the screen version of Hillbilly Elegy is . . . not bent on making a case for how poverty is the fault of the poor,” she also believes the movie is “not about anything else either.” She perceives the characters as “selective evidence shoring up an argument that’s too distasteful for [the film] to make.”

However, the movie clearly credits poverty to generational issues. At around the hour mark, Bev refuses treatment as she watches her son charge thousands of dollars on various credit cards to pay for two weeks of her rehab. Vance angrily yells at his mother outside the center, criticizing her selfishness and lack of willpower, even asking her if she is “just too lazy to try.”

If the scene stopped here, the critics might have a valid point, but it does not. Lindsay responds to Vance’s criticisms: “Don’t be stupid . . . Mom and Aunt Lori, they had it worse than us. It was a war in that house.” The film then shifts to a flashback depicting some of Bev’s trauma—namely her father’s alcoholism and her mother, Mamaw, responding to numerous beatings at his hands by setting him on fire. These scenes show that Bev didn’t have a support system, especially from her mother. And this realization contextualizes Bev’s addiction just as Vance does in the book—not excusing it, but explaining it.

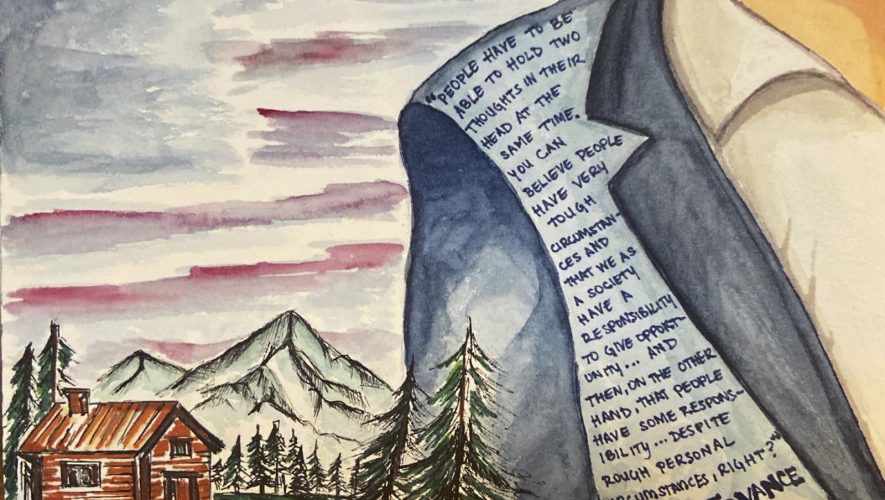

In a recent interview about the movie’s negative reception, Vance expanded on the film’s conclusion:

“People have to be able to hold two thoughts in their head at the same time. You can believe that people have very tough circumstances and that we as a society have a responsibility to give opportunity and hope to people no matter the circumstances they came from and then, on the other hand, that people have some responsibility and some personal agency despite rough personal circumstances, right?”

While the film does imply that people must make better choices to overcome poverty—namely working hard, following the law, and choosing a better path—it does not blame poor people for being poor. Yet, critics seemed to misrepresent the film willfully to appeal to their preconceived narrative.

Take Sarah Jones at Vulture, who opens her article stating that she “did not expect to like this movie.” When Jones describes the scene at the rehabilitation center, she interprets the movie’s depiction of Bev as “the culprit, a recalcitrant good-for-nothing who let her health insurance lapse and can’t muster a little gratitude when her suit-jacketed son tries to put her stay on his credit cards.”

However, the director clearly shows Bev changing her mind about treatment after watching her son struggling to charge the expensive fees on his credit card, with Bev even firmly stating that she’s “not a charity case.” The movie is clear: Bev didn’t want to take anything else from her son because she already felt that she had taken enough. At best, Jones misrepresented the scene because she forgot what happened; at worst, she was too busy trying to confirm her own biases. Either way, her review fails to understand and examine the film’s tenets—a disservice to those looking for a critical take.

Other critics blame the film for oversimplifying Vance’s Appalachian upbringing and for intertwining immorality and poverty.

Having read the book and watched the movie, I will attest that—as all film adaptations do—the movie simplifies its source material. But I entirely disagree with the critics who claim that Hillbilly Elegy fails to feature complex ideas. The movie and the book have the same overarching thesis: sometimes, you have to leave behind the people you love for self-preservation.

In the last fifteen minutes of the movie, Vance chooses to leave his mother in a motel room after she almost relapses—even though he seriously considers staying when she asks him to—in order to get to an interview with his top-choice law firm the next morning. He helps his mother in every way he can but does not risk his future. It is a powerful and controversial conclusion that many critics overlook in order to construct their narrative.

Hillbilly Elegy does not vilify poverty, as so many critics claim. It places some responsibility on the individual but acknowledges the generational challenges that make assuming this responsibility difficult. Vance is not the hero of the story, and Bev is not the villain. Vance’s future successes aren’t presented as a consequence of his superiority, exceptional talent, or work ethic. They are a product of his Mamaw’s intervention and his support system—all things Bev never had.

Critics do not hate Hillbilly Elegy because it blames the poor for being poor or oversimplifies Appalachia. They hate Hillbilly Elegy because of their preconceived notion of Vance’s right-leaning political beliefs, which are not discussed in the movie. Sarah Jones at Vulture even criticized Vance’s politics explicitly during her movie review, portraying him as connected to the alt-right when he is a moderate conservative.

Furthermore, there is a scene in the movie that explicitly addresses systemic barriers. An hour and a half into the film, the story flashes back to when Mamaw took custody of Vance. We see her requesting extra food from Meals on Wheels and struggling financially to support her grandson. Through these scenes, the movie shows how necessary Mamaw’s sacrifices were for Vance’s success.

Vance also ascribes the critics’ negative responses to his politics: “There are ways in which I sort of fit comfortably in the conservative coalition and ways in which I don’t. But I’m very clearly on the American right, so I think [it’s] a little bit of ‘we’re giving this conservative too much air time, so let’s change that.’” The critics assigned beliefs to the movie that weren’t actually present, ignoring the heartfelt, impactful, and effective storytelling to criticize an irrelevant notion of poverty they incorrectly associate with the right.

Hillbilly Elegy did not vilify the poor, but the critics certainly vilified Vance and his discussion of the plights of middle America. Another Vulture critic deemed “the Netflix adaptation and the book . . . unnecessary; nobody needed to ‘suddenly’ understand the Appalachian region or its problems, because Appalachian studies is a real field of scholarship. You can get degrees in it!”

To truly understand how ridiculous this review was, imagine if the critic said this about a film focused on African Americans or LGBTQ+ people. By that logic, films like Get Out, Moonlight, or Call Me By Your Name aren’t necessary because we have African American or queer studies. Just because you can study a topic does not mean that laymen understand it. There is value in creating an artistic depiction of other cultures, allowing audiences to forge emotional connections and sympathize with those portrayed.

Hillbilly Elegy humanizes low-income rural Americans, something that critics seem to believe is unnecessary, but it is actually critical to achieving a culturally unified, or even civil, America. The critical response to Hillbilly Elegy mirrors the US’ ignorance toward poverty in middle America.

Rural America has declined for decades as urban population centers have grown, largely because of cheapening rural resources and labor. Rural Americans, including the Vance family, have suffered from outsourcing, automation, and technological progress. Between 2001 and 2018, the US–China trade deficit effectively eliminated more than 3.7 million jobs, 75 percent of which were in manufacturing.

Shrinking industry continues to hit historically major manufacturing hubs in Ohio and Pennsylvania. In 2019, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan each lost more than four thousand factory positions. Globalization is a critical element of economic development, but there are overlooked consequences to progress. We can’t artificially reinstate these industries; rather, we must—as Vance explained recently—help rural Americans transition into more lucrative and sustainable careers.

Liberal policies are disconnected from middle America, exacerbating inequality between rural and urban voters. For example, student loan forgiveness would require the working class to subsidize college debt. Climate action policy—primarily rules established by the Environmental Protection Agency—hurts rural industries, notably agriculture, coal, and manufacturing. Abolishing the electoral college would make rural voters feel even more disenfranchised, only exacerbating the culture war.

Despite supporting policies like these, some Democrats, then, have the audacity to say rural voters are voting against their interests.

And now critics have the audacity to condemn Hillbilly Elegy for “misrepresenting” Appalachia, “blaming” poor people for being poor, and “intertwining” immorality and poverty. They disliked the movie because they disagreed with Vance and willfully misrepresented the film to align it to their preconceived perspective.

While responding to a negative review, Princeton professor Robert P. George wondered if the critics who want people to skip Hillbilly Elegy “might have . . . I dunno . . . an agenda?” I think so, and George does too, answering that “The campaign against the film—made by the standard-issue liberal filmmaker Ron Howard, by the way—is purely political.”

Even when critics discuss the film’s acting, their ideological bias rears its ugly head. The Atlantic’s Simms characterizes Mamaw’s portrayal as “steely goofiness—dressed in a fright wig and baggy sweatshirts, she bustles around every scene cursing and yelling tough-love homilies at the camera lens.” He accuses the actor of misrepresenting Mamaw and Appalachia, but the portrayal aligns with how she actually behaved.

Hillbilly Elegy does not deserve the backlash it has received. While the film does somewhat credit individual choice in the poverty conversation, it does not ignore generational issues. Having a success story doesn’t mean there were no challenges, and it doesn’t imply that there are no government-sponsored solutions to those challenges.

The only thing these critics prove is their inability to analyze films that do not confirm their biases. Through this failure to fairly review art, critics deter film studios from taking chances on unconventional stories, leading to fewer films tackling controversial social issues. And this gatekeeping only stiffles conversation, further limiting our understanding of one another.