The Electoral College is the entity that, despite ongoing popular opposition, continues to choose the leader of the free world. In the College, there are 538 total electoral votes, and the number of electoral votes each state receives is equal to the number of Senators plus the number of House Representatives, ensuring a minimum of three electoral votes for every state. The candidate who receives the highest popular vote in a state wins that state’s electoral votes – regardless of the margin of victory. (That said, there a few states which do split the votes, but for the most part this is a winner take all-system.) To note, over half of the US population has consistently spoken in annual surveys, since 1967, that they wish to see the Electoral College replaced.

The mechanics of the Electoral College augment the strengths of the two dominant political parties, Democrat and Republican, and wipe out nearly all hope for third-party candidates on the national stage. In order for a third-party candidate to receive any electoral votes, he or she must earn more votes than a Democrat or Republican in a state – and this is all but impossible against such thoroughly entrenched political parties.

The 1992 election results for Ross Perot demonstrate this deficiency in the Electoral College. Perot, the candidate for the Reform Party, garnered nearly 20% of the popular vote, but he did not win a single electoral vote, because his support was not sufficiently concentrated in any single state.

Think about that: one out of every five voters cast an entirely insignificant vote. The act of voting had symbolic value because voters were still able to express support for the candidate they thought would best run the country. But if one out of every five voters supports a candidate – and the candidate fails to gain even one of the 538 electoral votes that actually decide who becomes president – is that really fair?

In fact, the most recent third-party candidate to enjoy any measure of success was incumbent president Theodore Roosevelt, who ran on the third-party Progressive ticket in 1912. He received 88 electoral votes, which constituted a majority, but is a small number relative to the one required for victory in today’s two-party system, at least 269.

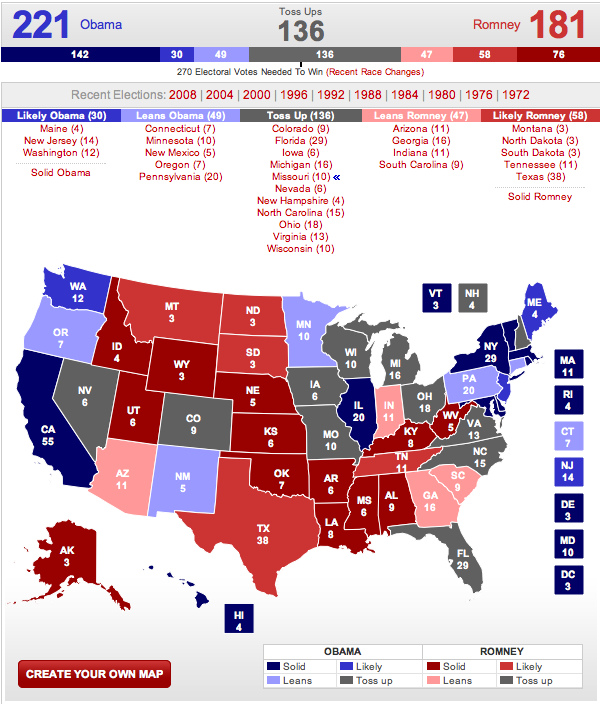

In terms of the upcoming election, it appears that the next president of the United States will be decided by the voters in the swing states of Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and maybe four other such states. This means that in reality a vote for the Obama in Ohio is going to matter a whole lot more than, say, a Republican vote in California or a Democratic vote in Texas, as those particular states are always won by the Democratic and Republican candidate, respectively.

Over the years, there have been many attempts to alter our method of presidential election. One of the solutions that has been proposed involves replacing the Electoral College with a National Popular Vote, in which one person equals one vote, and whichever candidate receives the most votes wins. The Electoral College would be rendered null.

One of the common arguments against the National Popular Vote is that, in a close race, recounts would occur in nearly every state. With every vote now actually counting toward the race’s outcome, both sides would be up in arms over voter registration laws (even more angrily than now), accusing each other of corruption and ballot stuffing. The presidency would likely not be decided until a week after election day. During that week each state will have done a recount and the Supreme Court will have likely stepped in. Even then, controversy over the final decision would rage for a while, seriously undermining the incoming President’s authority and diminishing his political capital.

On the other hand, one must consider the fact that the Electoral College has also produced its fair share of recounts. The 2000 election included an extremely close race for the presidency. By the end of election night, the two candidates (D-Al Gore and R-George Bush) were in a virtual tie in terms of the electoral vote, and it came down to whomever could win the state of Florida.

However, in terms of the popular vote, it was not even close. A solid half-million more citizens voted for Gore than for Bush (Sheppard 2001). Nevertheless, those extra 500,000 votes did not help Gore win the election; several thousand votes in a couple counties in Florida were enough to render those votes meaningless.

Solving the recount issue can be as simple as looking to the practices of other countries. In Brazil, the government has invested in simple touch-screen electronic voting machines that a largely illiterate population (almost 50%) understands and which can accurately state the results of an election in the hours following the closing of the polls (Mira 2004). In contrast, many regions of the United States (especially in rural areas) still rely on the old-fashioned paper ballot, which is frequently misread and misinterpreted by voters. In the case of the infamous 2000 election, some votes actually needed to be counted by hand in certain counties in Florida. If the United States invested in modern technology to record votes, the recount issue could be dismissed.

This raises the question, then: why do we still use the Electoral College to elect our president? According to Michael Dukakis, the Democratic nominee for president in 1988 and a distinguished professor of political science at Northeastern University:

“The electoral college is a profoundly undemocratic institution. It is forces campaigns to, in essence, conduct a seven-state campaign, rather than a fifty state campaign a true democracy should have.”

Alex Keyssar, a professor of Political Science at Harvard University, concurs:

“The Electoral College does not conform to our modern interpretation of democracy, which is one person, one vote …The question we should be asking is, why do we still have the Electoral College? In any state where either political party feels like it has a secure position, it’s easier to stick to the Electoral College and winner-take-all system. You know you can deliver your state. There’s always a resistance to change among people who know the rules and how to play the game…the problem today is overcoming a short-sighted partisanship.”

Where do we go from here? If the Electoral College is removed, what will replace it? If we wish to align our electoral mechanism with that of a true democracy, we will adopt the popular vote system, under which one person receives one vote, and whichever candidate receives the greatest number of votes wins.

The consequences of installing such a system would include a shift by all candidates to the center of the political spectrum, as over two thirds of Americans do not identify with either party; rather, they classify themselves as being somewhere in the middle. This would also likely precipitate a shift in campaign strategy, moving the primary focus from swing states to the urban areas which are home to most of the population.

In the end, we cannot discuss the future without first addressing the present. If the American people wish to see the Electoral College replaced, and they have indicated that they do, then they must protest. The government serves the people, and the public must rally support for its cause through the use of one of the strongest modern forces for change: the internet.

Current efforts to replace the electoral college include commoncause.org, which is a strong grassroots organization with over 400,000 members. It is active in thirty-five states, and it advocates the installation of the National Popular Vote. In its own words,

“Under the National Popular Vote (NPV) plan, states agree to allocate all of their electoral votes to the candidate who receives the most votes nationwide. The agreement takes effect only if states with a combined total of 270 electoral votes – a majority — join the agreement. This plan would make every citizen’s vote count equally.”

Common Cause has so far had nine states sign this agreement, including Massachusetts, Maryland, Illinois, and California. The NPV is also being considered in over a dozen other states, and it has passed through at least one house of congress in each. If you wish to enjoy truly fair representation, then get up, go out, support an organization such as Common Cause, or write to your senator or representative. Let them know that this is what the people want.

Down with the Electoral College.

Evan Bruning

Political Science ’17

Holmes, S. (1992, October 5). The 1992 Elections: Disappointment — News Analysis Eccentric but No Joke; Perot’s Strong Showing Raises Questions On What Might Have Been, and Might Be – New York Times. The New York Times – Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. Retrieved October 12, 2012, from http://www.nytimes.com/1992/11/05/us/1992-elections-disappointment-analysis-eccentric-but-no-joke-perot-s-strong.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Mira, L. (2004, January 4). For Brazil Voters, Machines Rule . wired.com . Retrieved October 12, 2012, from http://www.wired.com/techbiz/media/news/2004/01/61654?currentPage=all

Sheppard, S. (2001, March 23). President Elect – Articles – An analysis of the U.S. Presidential Election of 2000. President Elect. Retrieved October 12, 2012, from http://presidentelect.org/art_sheppard_e2000an.html

U. S. Electoral College: Frequently Asked Questions. (n.d.). National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved October 13, 2012, from http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/electoral-college/faq.html