War between states no longer starts on the battlefield. States continue to pursue hegemony—being powerful enough to dominate all other states. As weaker states become stronger, other powerful states will attempt to undermine them to prevent the rise of an alternative unipolar or bipolar power balance.

Within the modern context of nuclear proliferation and the threat of mutually assured nuclear destruction, traditional warfare has become too costly. In 2020, the crusade against bipolarity takes the form of cybersecurity breaches, support of resistance militias, and, most notably, economic warfare.

The Tragedy of Power Politics

Realism posits that states are rational actors that aim to increase their power relative to others. In his 1979 treatise Theory of International Politics, Kenneth Waltz coined a new branch: neorealism. Conflict and the pursuit of hegemony are explained not by flaws in human nature or the characteristics of individual powers, Waltz wrote, but by the balance of power between major actors in the international system.

John Mearsheimer’s neorealist theory on modern warfare applies to international conflicts regardless of whether fighting happens on the ground. Mearsheimer built upon Waltz’s ideas, outlining how state interactions are typified by fear, self-help, and power maximization.

Great powers fear each other because they cannot trust each other and, as a result, aim to maximize their relative power to ensure safety and resilience. In the same vein, because states cannot trust one another, alliances are temporary and fragile. Mearsheimer argues that “even when a great power achieves a distinct . . . advantage over its rivals, it continues looking for chances to gain more power.”

States always act in their self-interest, a phenomenon Mearsheimer calls “self-help.” Not unlike the classical realist’s understanding of human nature, all states look to take advantage of one another and prevent other states from taking advantage of them.

Power maximization, the final pattern of state behavior, depends on whether the state cares more about relative or absolute gains. Countries that prioritize relative gains aim to acquire more power than any other country. Those who prioritize absolute gains desire maximum gain for themselves, regardless of whether another state is gaining more.

States use calculated aggression when dealing with rivals. States that have a substantial advantage over their rivals behave more aggressively; those that don’t “consider offensive action” and are “more concerned with defending the existing balance of power from threats by their more powerful opponents.”

Great powers always aim to gain power over their rivals to become hegemons. Regional hegemony—dominating a distinct geographical area—is common because oceans have a “stopping power,” meaning states will not try to control distant regions that pose no threat to them. According to Mearsheimer, there has never been a global hegemon, and there likely will not be one soon unless a state achieves clear-cut nuclear superiority.

Regional hegemons will try to prevent great powers in other regions from acquiring the same status for fear that a rival will surpass and dominate the original state’s region as well. These states are more likely to adopt a relative gains strategy.

The US–China Trade War

In 2018, President Trump began to apply tariffs on China and other Asia-Pacific countries. His goal was to pressure them into a trade deal that he perceived to be more beneficial to the United States. Trump claims that the US has been taken advantage of in trade agreements, citing the country’s trade deficit with the rest of the world—hundreds of billions of dollars annually—as evidence of a diminishing domestic manufacturing sector.

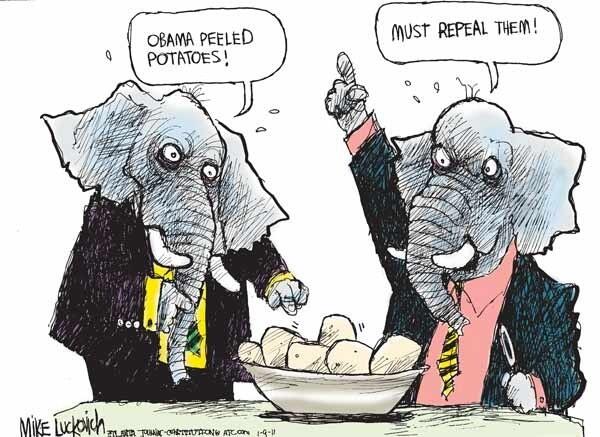

Since then, there have been many attempts to end the escalating conflict, but truces have been short-lived. Although Trump’s trade deals have differed little from those negotiated by his recent predecessors, Trump has been quick to criticize President Obama for prioritizing absolute gains and hurting Americans in the process. However, research predicts that the current trade war—with a 25 percent tariff on all US–China trade and a 10 percent drop in equity markets—would cost the world $1.2 trillion in economic output if it escalates.

To add insult to injury, in August 2019 the US increased retaliatory tariffs from 25 percent to 30. If characterized as an act of calculated aggression, Trump believed that the US had a marked advantage over China, while Chinese tariffs were an attempt to defend the existing balance of power.

The US–China trade war serves as an example of one regional hegemon attempting to undermine a rising one. While some may argue that the application of protectionist measures such as tariffs has come too late to prevent Chinese hegemony in Asia, the goal of the trade war is to weaken Chinese manufacturing while bolstering the US economy, implying an economic security dilemma of sorts.

A neorealist might argue that a rational actor would not wage traditional war over economic conflict, and that because China has never used military action in trade disputes, neorealist theory does not apply. But this is not the case. Threatening and executing aggressive economic responses—instituting and increasing tariffs, for instance—is the economic equivalent of threatening physical force. It’s merely a different form of war.

Mearsheimer also applies John Herz’s security dilemma to war theory. Herz was known for using game theory to explain state action. He argued that the actions states take to increase their security will decrease the security of other states. In the case of a trade war, as one country raises a tariff the other is worse off. Mearsheimer adds that how much states fear one another dictates the “severity of their security competition and how likely they are to fight a war.”

Who would win said war depends on the balance and magnitude of their potential and actual power. Potential power is a state’s capacity for military power, which directly correlates to population and wealth. Actual power is based entirely on land power or the strength of ground, air, and naval forces. China and the US lead the world in actual power.

Today, when the threat of mutual nuclear annihilation makes actual power somewhat obsolete, potential power becomes more relevant. In 2010, research estimated that China’s GDP would surpass America’s by 2020 and would be twice its size by 2030. The growth in the Chinese economy increases its potential power, enabling it to amass actual power in the future.

Conclusions

John Mearsheimer’s neorealist theory explains the US–China trade war in a modern context where armed war is less likely. Today, potential power has become increasingly relevant, making his theory applicable to power plays like economic attacks.

Ideological difference can and does motivate conflict, as it did in the Cold War. But it is not a chief driver of today’s conflicts. Trade wars are a challenge between states for power. Conflicts motivated by ideology are in truth conflicts over hegemony.

By characterizing economic conflicts as a form of war, we can apply tried and true neorealist theories to modern disputes, allowing for analysis and prediction long before sufficient data is accumulated to create an all-encompassing model. As power struggles continue to motivate state behavior, models based on the assumption of rational state behavior are validated.

The analysis of economic conflict spans beyond the world of high-stakes business. The ability to predict and prevent trade wars and other economic conflicts can protect industries at the microeconomic level, preserving the livelihoods of people like Chinese miners and American farmers. Those affected by trade wars can use Mearsheimer’s theory to advocate for themselves. Governments can use it to recognize the true costs of their policies. And everyone else can acknowledge what is becoming increasingly apparent: that war is no longer confined to the battlefield.