American elections are a disaster.

On the surface, they’re viewed as the perfect model of democracy, one that all developing countries should follow. But if you lift the lid, it’s a horrible, dark, slimy mess, from the continued existence of caucuses, to voter disenfranchisement, to the undemocratic Electoral College, to an excess of money in politics.

It’s easy to accept that despite its less-desirable quirks—the outcome deviating from the will of the majority and billionaires buying their way onto debate stages, for example—our system is the best option. How could it not be? It’s always been this way, and changing it is ridiculous. The Founding Fathers knew exactly what they were doing. They may have been slave owners who gave rights to only White men and counted a Black person as three-fifths a White one, but they understood how to establish a democracy!

The Constitution isn’t the word of God. By design, the electoral process set up by the Founding Fathers doesn’t work for the people who need it most. The first step to fixing it is accepting that change is necessary. While some problems need resolution through a constitutional amendment or by overturning a Supreme Court decision, none are impossible to address.

Caucuses

Once every four years, Americans—at least those who follow politics—care about Iowa. Politicians and journalists flock to the Iowa State Fair to ride the giant slide and eat pork chops off of sticks. Presidential hopefuls trek across the state, holding rallies and town halls everywhere from bars to barns, all leading up to the Iowa caucuses.

While primaries and caucuses both select candidates, they are not the same. Caucuses are public meetings where community members display their support for candidates. Instead of casting votes throughout election day, caucuses are held at a specific time and place, and voters must be present in order to participate. Different areas of the room are designated to different candidates, and supporters separate into groups depending on their candidate. In most Iowa precincts, at least fifteen percent of attendees must be in each candidate’s corner. If a candidate doesn’t reach that threshold in the first alignment, they are deemed unviable, and their supporters must realign to a different, viable candidate. The results in each precinct are translated into state delegates, which eventually determine who gets the nomination.

Iowa has used caucuses since the 1800s. It switched to a presidential primary in 1916 but changed back the following year due to high costs and low turnout. This preference for caucuses is likely due to Iowa’s small population (just over three million), which makes caucusing easier there than in a state like New York. Further, caucuses require that voters be actively engaged in the election process, another potential draw for this method.

For many Iowans, it’s a source of pride to be the first state to vote for the presidential nominee. They take their role seriously. But the Iowa caucuses are not the best way to pick a nominee.

Based on recent elections, many are beginning to support doing away with caucuses. During the 2020 Iowa caucus, many voting sites were unorganized. Sites were run by volunteers, many of whom did not receive adequate training on the new vote recording app. The phone lines that reported results got clogged, leading to a delay in declaring the winner.

The Iowa Democratic Party further complicated reporting by releasing three different numbers from each caucus site: the vote total from the first alignment, the final vote total, and the state delegate equivalents. The numbers provided insight but sparked debate over which number determined the winner. Some argued that the vote total was more important, as it represented the actual number of people who supported each candidate, while others, including the Iowa Democratic Party, argued that the state delegate equivalents were more important, as delegates determine the eventual nominee.

Despite the confusion around the results, former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg declared victory. Once the votes were finally tallied, it was proven that Buttigieg won only in delegates, while Senator Bernie Sanders won the most votes.

Iowa isn’t the only state to hold caucuses—Nevada, North Dakota, and Wyoming do as well. The latter two don’t receive as much attention, as they come later in the primary cycle. Nevada is emphasized as the first caucus state to vote with a large minority population. While Iowa is over ninety percent White, Nevada is about 66 percent White.

The 2020 Nevada caucuses ran more smoothly than Iowa’s. This year, Nevada introduced early voting. Rather than showing up to their caucus site, voters could submit a ballot ahead of time. Of the one hundred thousand participants, seventy-five thousand voted early, indicating that voters seem to prefer primaries over caucuses.

Caucuses disenfranchise plenty of voters. In order to participate, voters must show up to their caucus site in person and may have to remain there for several hours. This places disabled people, parents, and late-shift workers at a disadvantage. There are few resources available for deaf voters, who may not be able to handle a crowded, loud room. It’s also more difficult to participate if you can’t stand up for long periods of time. Three hundred thousand voting-age Iowans have disabilities, and each of them may face particular hardships when caucusing. For those busy on weeknights, it may be impossible to show up. In 2016, turnout in the Iowa caucuses was only 16 percent, while New Hampshire’s primary election drew 52 percent.

Caucuses are an outdated voting method that disenfranchises many voters and complicates vote recording. Replacing caucuses with primaries would be a major improvement.

The Electoral College

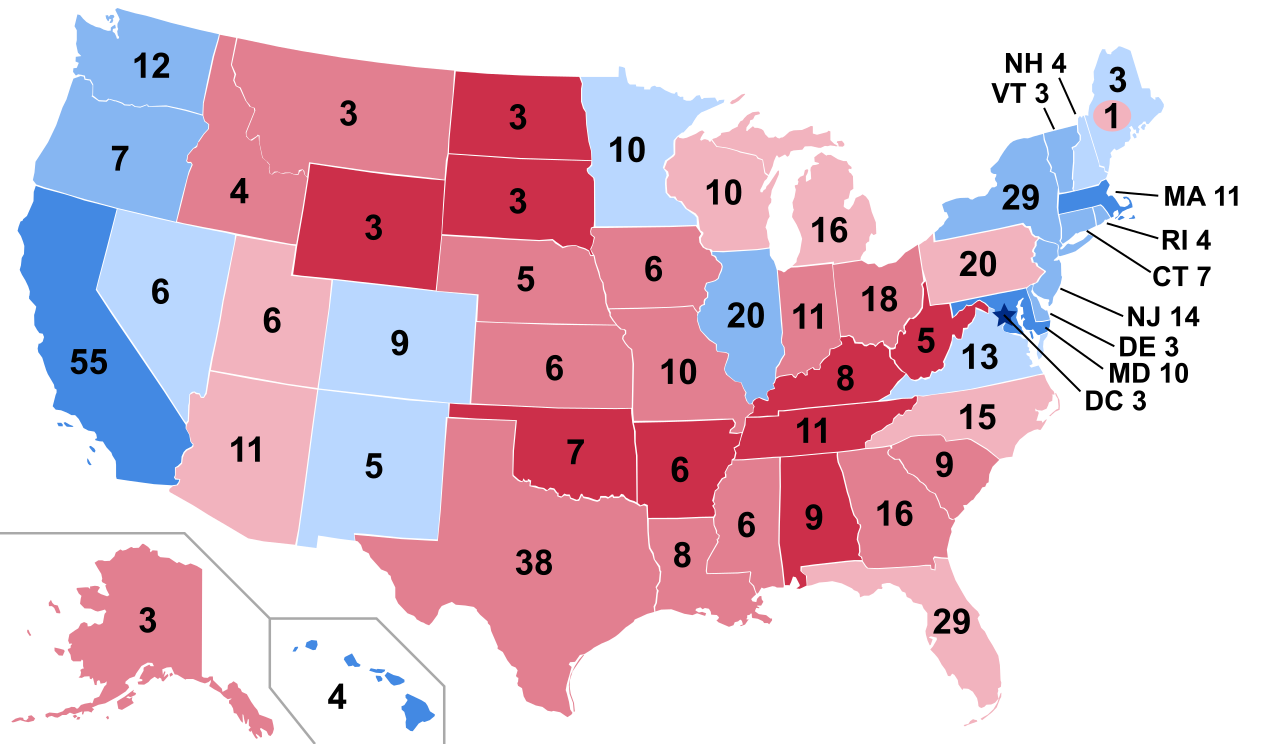

The method of awarding delegates in a caucus mirrors the Electoral College, the body that actually elects the president. Each state has a certain number of electoral votes apportioned, somewhat, based on population. Whoever wins the popular vote in the state wins the electoral votes—except in Maine and Nebraska, where votes are broken up by district, meaning votes could be split. Rather than winning the majority of the national electorate, candidates need a majority in enough states to reach 270 electoral votes.

Supporters of the College argue that it ensures that small states have as much say as big states; however, it actually favors small states above big states. A vote in Wyoming, for example, is worth three times the national average. Because of this imbalance, candidates don’t need to campaign in every state. The outcome of the election depends solely on “swing states,” where the outcome in any given year is less certain. In 2016, two-thirds of general election campaign events took place in just six states.

The winner of the popular vote has lost the Electoral College five times. The 2000 election between Al Gore and George W. Bush was decided by the results of a single state, Florida, where the race was too close for a winner to be declared. The Supreme Court ruled that a recount was unconstitutional, handing Bush the victory. The 2016 election results were the largest-ever discrepancy between the popular vote and the Electoral College—Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by three million votes, but failed to win the Electoral College because she lost key states in the Midwest.

While some Democrats have proposed eliminating the Electoral College, a Democratic president couldn’t do so through executive order. Rather, a constitutional amendment is needed, which requires agreement across state and party lines as well as ratification by three-fourths of all states.

It’s been nearly three decades since the Constitution was last amended. Under the current Senate leadership, it’s unlikely that any proposal would gain traction. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) once implied that a plan to elect the president by popular vote was “a genuine threat to our country.”

Several states are working to surpass the Electoral College without getting rid of it entirely. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact commits states to give their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of who wins the state. The compact will take effect once enough states have joined to reach 270 electoral votes; so far, the bill has been signed into law by fifteen states and Washington, D.C., for a total of 196 electoral votes.

In 2019, four states joined the compact, the most in one year since 2008. Still, the compact isn’t likely to take effect anytime soon. Small states, swing states, and Republican strongholds, which benefit from the Electoral College, are less likely to sign on.

Some consider the compact unconstitutional under Article 1, Section 10, which says that “no state shall, without the consent of Congress . . . enter into any agreement or compact with another state.” Proponents contend that the compact is permissible under the Supreme Court’s interpretation in US Steel Corporation v. Multistate Tax Commission, in which the court affirmed the constitutionality of compacts as long as they do not usurp federal power. Because the Electoral College was established by the Constitution, any actions to surpass or alter it would likely be challenged in court. It is difficult to predict whether the compact would be upheld, but it would entail a tough legal battle.

It is possible for the compact to take effect, but it would require the same momentum seen in 2019 and a strong legal defense. If the compact passes and is upheld by the courts, it could overcome the Electoral College without a constitutional amendment.

Voter Disenfranchisement

Partisanship may turn off voters from participating in an election—if they know a Republican will win the state, a Democrat may find it pointless to vote in Tennessee, and vice versa for a Republican in California. Many voters, however, do not opt out of elections by choice. Systematic disenfranchisement means that the votes of millions are not counted.

Voter ID laws, felon disenfranchisement, confusing registration processes, and absentee ballot rules all prevent Americans from voting. Voter ID laws are supposedly implemented to reduce voter impersonation fraud, but the rate of fraud is basically zero. These laws disproportionately affect voters of color and low-income voters who may not have the resources to get a photo ID such as a driver’s license or passport.

Felon disenfranchisement—barring felons from voting even after they’ve completed their sentences—means that 5.85 million people across the country, mostly men of color, cannot vote. While most Americans oppose allowing felons to vote while incarcerated, they do support restoring voting rights to those with completed sentences. Following the will of the majority would mean enfranchising millions who have served their time and are ready to reintegrate into society.

The voter registration process also impacts turnout; voters may not be aware of registration deadlines or the need to register at all. While absentee voting is an option for those who can’t make it to polls on Election Day, some states limit the reasons someone can request an absentee ballot. In several states, voters who register by mail must vote in person in their first election. New Hampshire recently implemented a law that required voters to have a state driver’s license in order to vote, which confused many out-of-state college students.

If the United States was the model of a perfect democracy, it would encourage voting. The higher participation is, the more the public benefits. Active voter suppression indicates something sinister and broken about the American election system.

In voter turnout—a key indicator of a democracy’s strength—the United States lags behind most developed countries. If the US wants to be a model, leaders should do everything in their power to increase voter turnout in every demographic in every part of the country.

Every citizen aged eighteen or older should be permitted to vote in American elections, and barriers to voting should be reduced as much as possible. This means ending voter ID laws and felon disenfranchisement, as well as expanding access to absentee voting. Americans deserve to be led by people whose ideology and goals most fully align with theirs, not power-hungry politicians who disenfranchise voters to keep their jobs.

Big-money Contributions

The amount of money poured into campaigns every election cycle is astronomical, and it’s becoming more expensive to run for office. Candidates need to amass ungodly sums—in some cases over $10 million—in order to be anywhere close to viable, particularly in national elections.

Several 2020 Democratic presidential candidates dropped out because they couldn’t sustain the amount of donations necessary to keep running. Meanwhile, the two billionaire candidates—Tom Steyer (worth $1.6 billion) and Michael Bloomberg (worth over $60 billion)—could pull a couple stacks from their bank accounts and buy up airtime wherever they pleased. Bloomberg spent $433 million on ads; Steyer spent $154 million, and his campaign ran ads in every state. Either candidate could have bought a Super Bowl ad (this year, thirty seconds cost a whopping $5.6 million) without making a dent in their personal wealth. Bloomberg, the only candidate to run a national ad, purchased a sixty-second spot.

Allowing billionaires to use their personal wealth to campaign for office sets a precedent for increased spending in elections. The more money they spend, the more other candidates have to raise to compete. Candidates without personal fortunes turn to lobbyists or super political action committees (PACs)—committees that can raise and spend unlimited funds on election-related expenditures.

Most of the Democratic candidates pledged to accept only small-dollar donations. However, as candidates began dropping out due to insufficient funds, the ones who remained were forced to choose between their integrity and their political aspirations. Persist PAC spent millions supporting Senator Elizabeth Warren so she could compete with Bloomberg. Senator Bernie Sanders’ de facto Super PAC, Our Revolution, raised nearly $1 million between 2016 and 2018. Most of this financial support came from donors contributing six-figure sums.

Other politicians don’t care where their money is coming from as long as they have enough to get re-elected. They’re also inclined to vote for their donors’ interests. Researchers found a correlation between a rise in anti-environmental votes and an increase in campaign contributions from oil and gas companies. So far in the 2019–20 election cycle, oil and gas lobbying groups have donated over $15 million to congressional races.

The solution to this issue seems simple: get wealthy donors out of politics. Stop letting corporations, lobbying groups, and Super PACs donate millions. Change the way campaigns are financed so that billionaires can’t buy the nomination. Overturn Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission and Buckley v. Valeo, Supreme Court decisions which allow corporations and labor unions to spend unlimited funds to elect their preferred candidates.

Unfortunately, campaign finance reforms are not easy to pass. In January 2019, Congressman John Sarbanes (D-MD) introduced the For the People Act, a wide-ranging bill that covered many areas of election reform, including campaign finance. The bill was passed by the House in March 2019, but the Senate has not taken action. Many Democratic politicians have made campaign finance a forefront issue, but without control of the Senate, federal reforms remain unlikely.

At the state level, there has been gradual progress over the past several years. In the 2018 midterms, several states passed campaign finance reforms. North Dakota and New Mexico established campaign and finance ethics commissions. Missouri created stricter finance laws for state lawmakers, including lowering the limit on campaign contributions to candidates for the state legislature. Campaign finance reform at the city and state level could help build national momentum.

Despite what the Citizens United decision may imply, corporations are not people, and they should not be treated as such. Politics should be about people. If people like a candidate enough to donate and eventually vote for them, then the candidate can keep their seat. If they can’t manage to get re-elected without accepting money from industries, then they don’t deserve to be in office.

Moving Forward

There’s an endless list of reasons why voters are apathetic towards politics and elections, and by some measures, that apathy is increasing. In 2016, 25 percent of non-voters cited they disliked the candidates or the issues they campaigned on. In contrast, only 13 percent of voters cited the same primary reason for not voting in 2012.

Democrats and Republicans are often accused of being “out of touch” generally and on specific issues, such as the environment. Furthermore, members of Congress have historically overestimated their constituents’ conservatism, implying that they don’t have a full understanding of public opinion. Elections are treated like sporting events, with ESPN-esque intros during debates and constant discussion of horse race polls, misrepresenting the value elections have for voters.

Americans like to romanticize the ideals of the Founding Fathers. But the Founding Fathers weren’t prophets and their word is not gospel. The world has changed since 1787. George Washington’s opinion about the current state of American politics is not an important consideration.

The last few national elections have revealed cracks in our electoral foundation. Our elections don’t work for those who need them most. It’s time for a massive overhaul. If we want to be treated as a model for the world, we need to take a good, hard look at our own democracy first.