The role of the hijab and its significance to the women who wear it is frequently oversimplified. Muslim American women must navigate multiple levels of pressures, social sanctions, and conflicting ideologies when they choose whether or not to veil. This article seeks to organize the various social dimensions of hijab into three spheres: the general American public, Muslim communities in the U.S., and personal life. Although there is a great amount of crossover and interaction among these spheres, they provide a useful logical framework for examining how ramifications of veiling and reasons for it compound in the lives of veiled Muslim women.

Before 9/11, Americans had a far more limited perception of Muslim women. Middle Eastern Muslim women were lumped in with views of other Asian women, which often unfairly painted them as exotic and content with being appendages of men. The Iranian Revolution and the Iran hostage crisis in 1979 thrust Muslim women into American media. The hostage crisis attracted so much attention in the U.S. that news channels had a countdown of all 444 days the hostages were held, and President Carter’s popularity was obliterated. Images of women in hijabs protesting suddenly appeared in all forms of media.[5]

This was only the beginning of the hijab’s life as a powerful symbol in the U.S. After the hostages were safely returned, veiled Muslim women were depicted as severely oppressed and without any semblance of agency, yet their voices were excluded from this dialogue.[4] Islam was attacked for gender inequality, while many other religions with similar gender politics were relatively free from such criticism.[4] [8] Meanwhile, the numbers of Muslims increased in the U.S.[7]

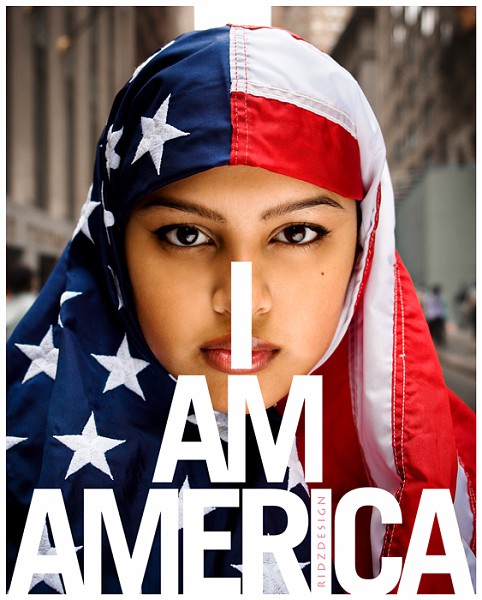

Many Muslim Americans reference their experiences in the U.S. in relation to 9/11. The terrorist attacks intensely altered the way America perceived Islam, and the way it treated Muslims within its borders.[5] Sweeping misconceptions characterized depictions of Muslims, particularly the myth that all Muslims were somehow associated with terrorism or “the enemy.” Those who visibly displayed their religion were especially targeted, and the hijab was the most easily recognizable way to display Islam.[3] Many veiled Muslim women found that no matter how devoted they were to their country and their religion, they still were not accepted as fully American.[3] [4]

American public opinion has conceptualized Muslim women as simultaneously permanent victims and guilty terrorist sympathizers since 9/11. Perceptions of Muslim women as not having agency have not fully diminished, but have been forged with suspicions of terrorism and the enemy at home.[3] Immediately after 9/11, many Muslim women were eager to continue wearing the hijab to prove that the majority of Muslim women had agency, were peaceful, and could still be devoted to their religion.[6] [8] However, over the years, the responsibility of being a representative of Islam and the burden of ignoring all the stares and assumptions became too heavy for some of these women.[6] Meanwhile, many more Muslim women remained or became committed to veiling.

In the American public sphere, Islam was increasingly portrayed as a political stance and a legitimate security threat rather than a religion. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan along with the attacks on the civil rights of Muslim Americans have frequently been presented in a “Clash of Civilizations” framework that makes American and Islamic coexistence seem impossible.[3] Political fear mongering also contributes to convincing some Americans that Muslims are naturally adverse to American values or prone to violence and extremism. This rhetoric allows a country that has always fiercely defended religious freedom to avoid realizing that it is being hypocritical when it steps on a minority religious group’s right to practice their religion.

In debates over several proposed blatantly anti-Muslim laws, strong arguments for religious freedom for Muslims have been noticeably absent. The treatment of Muslim public spaces as anti-American or as terrorist bases and of hate crimes against Muslims have frequently not been described as displays of religious intolerance. The NYPD distributed training material to its officers that profiled Muslims as terrorists, and many other police departments across the country then used the same materials.[3] [6] In Rutherford County, Tennessee in 2010, citizens filed a lawsuit to try to prevent the construction of a mosque and Muslim community center. In the case, they testified that Islam is not a religion and that the construction of the mosque is part of a Muslim plot to replace the U.S. Constitution with sharia law.[3] [9]

In this context, the hijab is seen a hostile and confrontational political marker and a symbol of being a suspicious other, rather than as a religious choice. This view empowers some Americans to discriminate against Muslims without feeling that they are engaging in religious discrimination.[3] Veiled Muslim women are left to cope with the politicization of their religion and of the hijab, which often interferes with their ability to find employment, receive an education, and even interact safely in the public sphere.[3] [4]

American society as a whole presents many challenges and pressures for veiled Muslim American women, but so do Muslim communities. These communities present new and equally complex rewards and ramifications for veiling. The majority of Muslim communities have patriarchal leaders and representatives, which further hinders Muslim American women’s ability to control their representation.[1] [3] All Imams are male.[8] Some male Muslim leaders are outspoken about gender equality and women’s rights being major tenets of Islam, and many Muslim American women are active and important members of their religious communities.[4] [8] However, this cannot possibly circumvent the need for Muslim women to hold leadership roles and to represent themselves to the American public.

International debate over the merits of hijab and its role in Islam is diverse, and these views are represented in American Muslim communities.[4] Wearing the hijab sometimes provides Muslim American women with close-knit social bonds with other veiled Muslim women, because of a shared experience of being an outsider in the U.S. post-9/11.[4] They can also gain moral and religious legitimacy in Muslim communities through veiling.[1] [10] Many feel that this legitimacy grants them greater freedoms and insulation from restrictions usually placed on unmarried or unaccompanied women.[10] However, often not veiling has the opposite effect for women. Muslim women who choose not to wear a hijab can feel othered and unaccepted in Muslim communities because they are unveiled.[4] [10] Muslim women can receive positive social sanctions in their communities for veiling and negative social sanctions for refusing to do so.

Muslim women experience many other conflicting pressures within Muslim communities in the U.S. Some American Muslims see embracing modernity and American culture as the cure for the poor treatment they have received post-9/11. To those who see conforming to American culture as a necessity, women in hijabs are resisting modernity and hindering Muslims from being accepted as Americans.[4] Many Muslim feminists have attacked the hijab as a cultural relic and a symbol of patriarchy, rather than an icon of religious devotion. Some veiled Muslim women feel that they are reduced to willing supporters of patriarchy in the eyes of these feminists.[1] [4] Veiled Muslim women can also feel resented by unveiled Muslim women, because they are perceived as trying to compete over who can be the most religiously devout.[4]

Muslim women who choose to veil often find that the hijab can affect their relationships. Within Muslim families, generational pressures influence women’s choice to veil. Some first generation American Muslim women, especially in their teens and twenties, feel pressured to veil as a means of maintaining the older immigrant generation’s culture. These women need to balance their American identity with the pressure placed on them to maintain their family’s culture.[10] However, sometimes when young Muslim women with westernized parents choose to veil, older unveiled Muslim women in their families follow their lead.[1] [10]

A major component of religious devotion is performance of religious rituals and beliefs. This performance does not end for devoted Muslim women when they leave the mosque or finish praying. It characterizes their choices in many arenas of their lives, including whether or not they veil.[2] Many veiled Muslim women highlight the role of conscious choice to veil and commitment to that choice as important in their religious lives. Because they see the hijab’s significance as originating in conscious religious choice, they feel that wearing it is a major part of their personal identities.[10]

The concept of conscious choice and commitment in religion is vital to dismantling the overly simplistic view of women in hijabs not having agency, but there are many more personal reasons why Muslim women choose to veil. Some American Muslim women find veiling empowering, because it is a display of pride in being Muslim, loyalty to their culture, or anti-imperialism.[4] Many Muslim women choose not to veil for feminist reasons, but there are also many who cite their feminist beliefs as a reason why they choose to veil. Muslim intellectuals disagree over whether veiling is religiously mandated by the Quran or whether is it a cultural tradition that has been attached to the religion through custom.[8] [10] Muslims who feel that the hijab is vital to women’s religious devotion frequently reference the role of modesty in Islam. They see modesty as a very important Islamic value for both genders, but believe men and women must express it in different ways.[10]

Another important aspect of the veil’s personal significance to women is the role it plays in their sexuality. Many veiled Muslim women express the belief that American culture exploits women by over-sexualizing and sexually objectifying them. These women see the hijab as liberating them from feeling sexually vulnerable to men and from being approached or harassed by men for explicitly sexual reasons. This empowers them to have more active lives outside the home in universities, workplaces, mosques and other public settings.[4] [8] Some veiled Muslim women report that their internal qualities are more likely to shine through when they are veiled, because the hijab draws attention away from their physical appearance.[4]

Interviews with veiled Muslim women about the hijab revealed an essentialist understanding of gender that favored equity and appreciating differences over what was seen as a more American push for equality, sameness and ignoring natural differences.[10] Some of these women even perceived the way their hijabs differentiated them from men as granting women their natural place of being more special and valuable.[4] Another component of this essentialist view is the frequently underlying belief that men cannot control their sexual urges and women owe it to themselves and to men to act as gatekeepers.[8] [10]

There are currently about one million Muslim women in the U.S., and about 43 percent of them choose to wear a hijab all or most of the time.[7] As the number of American Muslim women increases and the U.S.’ relationship with Islam becomes further complicated, even more pressures and considerations will impact women’s choice of whether or not to veil. The importance of acknowledging the complex nature of this choice and the need to dismantle arguments that seek to overly simplify it will increase as well.

Sarah Lombardo

International Affairs ’15

[1] Abdul-Ghafur, Saleemah. Living Islam Out Loud. Boston: Beacon Press, 2005. 1-201. Print.

[2] Avishai, Orit. “”Doing Religion” in a Secular World: Women in Conservative Religions and the Question of Agency.” Gender and Society. 22.4 (2008): 409-433. Print.

[3] Aziz, Sahar. “From the Oppressed to the Terrorist: Muslim American Women in the Cross-Hairs of Intersectionality.” Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal. 9.2 (2012): 191-264. Print.

[4] Bartkowski, John, and Jen’nan Read. “To Veil or Not to Veil: A Case Study of Identity Negotiation among Muslim Women in Austin, Texas.” Gender and Society. 14.3 (2000): 395-417. Print.

[5] Herndon, Kathleen. “Images of Muslim Women in the American Media.” Times and Issues Forum. Weber State University. Utah, Ogden. 06 2010. Lecture.

[6] Khalid, Asma. “Lifting the Veil: Muslim Women Explain their Choice.” National Public Radio 21 Apr 2011, n. pag. Print.

[7] Kohut, Andrew. “Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream.” Pew Research Center. N.p., 27 2007. Web. 11 Dec 2012.

[8] Rauf, Feisal. Moving the Mountain: Beyond Ground Zero to a New Vision of Islam in America. New York City: Free Press, 2012. 107-134. Print.

[9] Severson, Kim. “Judge Allows Muslims to Use Tennessee Mosque.” New York Times 18 Jul 2012, n. pag. Print.

[10] Williams, Rhys, and Gira Vashi. “Hijab and American Muslim Women: Creating the Space for Autonomous Selves.” Sociology of Religion. 68.2 (2007): 269-287. Print.