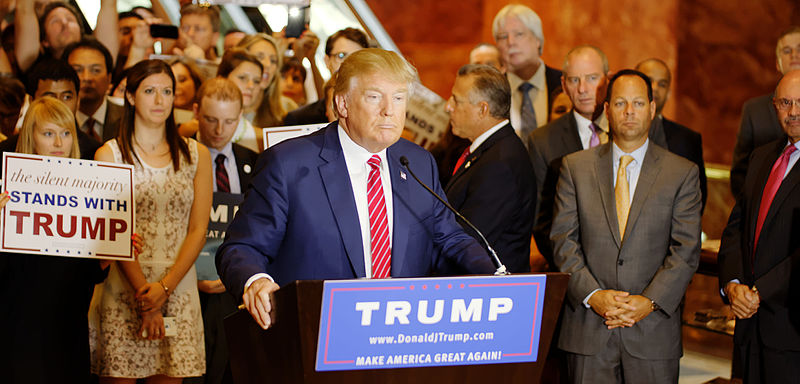

The 2016 primary season has been extraordinary in the way it has captivated voters, media, and the international community for such a sustained period. There’s a certain appeal to the train wreck that is Donald Trump’s ascent, with his endless supply of petty remarks and unrealistic policies, and the ensuing speculation and incredulity surrounding his runaway success. However, the force that is Trump is not the only factor making this primary season the media firestorm that it is. He is, rather, one manifestation of a particular sentiment in the country that is responsible for stirring up such a frenzy: dissatisfaction with the current political and economic scheme. Populism is no stranger to American politics, but its place in the current primary season is unique in its magnitude. The success of both parties’ underdog candidates is a result of these populist notions ricocheting off the country’s two very divided ideological camps. Making this phenomenon unique to 2016 is the role of social media and its function as a space for grassroots campaigning by the people, for the people.

Throughout America’s relatively short history, candidates have always sought to emphasize aspects of themselves that make them relatable to the everyday voter. It usually involves going to State Fairs and eating heart-attack inducing food, or regaling voters with stories of their working-class, humble beginnings. However, only a few candidates have fully embraced populist rhetoric as the basis of their platform. For example, the Know-Nothing Party of the mid-1800s seized on the public’s fear of Irish-Catholic immigrants, whom they viewed as threats to their employment. The party failed shortly thereafter due to a schism regarding their views on slavery.[1] A couple of decades later, the People’s Party (often known as the Populists) formed in the Midwest as a reaction to poor farming conditions that left them impoverished, while unregulated capitalists in the east grew exponentially richer. Those same capitalists charged high interest on loans to the farmers and exorbitant fees for the railroads on which the farmers depended. As a result, the Populists fought for a higher, more progressive income tax to break up the big trusts, and to nationalize the railroads.[2]

Does any of this sound familiar? Isn’t it strange how history repeats itself?

The United States has been experiencing a mix of these same factors for years now. An influx of immigrants, this time from South and Central America, has given Americans anxiety about their job stability. Adding to this fear is the reality that blue-collar jobs have significantly declined in the States due to cheaper labor in the developing world and higher productivity as a result of technological advances. In 1970, about one in four Americans worked in manufacturing. Now, it’s about one in ten.[3] This has created a culture of fear in parts of the country where manufacturing jobs have provided a stable livelihood and a sense of identity for generations.

But even in parts of the country that have not historically relied on factory jobs, people have become increasingly wary of growing income inequality. Bestsellers like Freakonomics and the Occupy movement have brought these facts to the foreground of many people’s minds. The concept of “1%” once meant nothing more than a hundredth, but now it brings to mind a much more politically loaded sentiment: that the average, hard-working American has the odds stacked against her.

However, what is particularly fascinating about this election cycle’s brand of populism is the dichotomy it has adopted. These forces of frustration, as they could broadly be considered, have collided with the country’s competing liberal and conservative ideologies. As a result, two starkly different forms of populist rhetoric have emerged, completely at odds with one another, yet reflective of America as a whole. They each have their own face. One is orange and wears a toupee. The other is a bespectacled Jew who is more accepting of his bald spot. They both like to shout, they both were initially laughed off as unviable, and they both are fiercely beloved by their supporters. That is pretty much where their similarities end.

Escalating this ideological divide is the power of social media. The 2008 election was simply too early to see much of this phenomenon, as Facebook at the time was merely for college students and barely a blip on most people’s radars. In 2012, of course, social media use was common, but an incumbent president and an establishment politician did little to stir up public interest in the election, at least not on the level that we are seeing this time around.

Social media has matured over the years since its invention. It is no longer used exclusively as a means to connect with friends and family. It has now taken on new functions to connect people who would not otherwise have met. It has rendered geographic location irrelevant in many ways. Realizing their potential some years ago, both Facebook and Twitter have shifted their focus to providing news and information to their users. Between 2013 and 2015, the percentage of users who accessed news via these platforms jumped from 52% to 63% for Twitter and 47% to 63% for Facebook. This increase was roughly the same across all demographics.[5]

Social media has also changed the way candidates interact with their prospective constituents. They can be more direct now, like Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz participating in the #NeverTrump hashtag on Twitter. However, the new channel of communication between politician and voter does not always work in the politician’s favor. Small events on the campaign trail used to give politicians a chance to speak to their constituents in a more intimate environment, but a proliferation of iPhone cameras can make any slip-up a viral internet meme in a matter of hours.[6]

However, a more interesting function of social media is not the more direct connection between politician and voter, but the online space that is created on social media for people to interact with other like-minded people. This is where Trump and Bernie have been remarkably successful and Hillary Clinton and the other Republican candidates have fallen short.

Let’s take the example of Clinton. She has been in the public eye for decades, enduring her husband’s horribly public affair as the world watched. Over the years, she has developed a tough skin, an overly polished persona, and a very carefully worded way of speaking. Now, in 2016, the entire nature of what it means to be loved and trusted by the public has shifted. Clinton now often comes across as fake and unlikeable. Scandals, however valid, now plague her campaign and people take to the comments sections of news articles to attack her. Her meticulously constructed persona is no longer viable in the social media era, in which voters crave relatability.

Her competition, however, is fresh-faced, honest, and willing to “tell it like it is” to their respective supporters. If you’re Trump, your tweets become headlines. If you’re Bernie, your speeches become viral memes. They both are extreme characters, but they have come to represent ideologies that have been increasing in extremity. Social media recirculates similar articles, sentiments, fears, and perspectives among like-minded people, allowing users to avoid exposure to opposing viewpoints. Because of this, voters’ preexisting beliefs (and fears) have grown stronger in conviction. This is one reason why conservative and liberal ideologies have grown in such radically opposite directions in recent years. And now that Obama’s term is nearly over and a new political era is set to begin, each side has adopted its own political candidate as a representative.

Facebook groups for Sanders and Trump have members in the thousands and hundreds of thousands, and can offer interesting insight into each side’s demographic: what they talk about, why they support the candidate, how they plan to undermine the competition. There are three Facebook groups dedicated to Bernie Sanders that have a member count in the 6-digits. The most popular is Bernie Sanders’ Dank Meme Stash, with well over 400,000 followers. It has even inspired a spin-off group, Bernie Sanders’ Dank Meme Singles, with over 10,000 followers.

Trump is much less successful in terms of numbers on Facebook, with only a couple groups of over 10,000 members. Clinton and Cruz fanbases are roughly equal in size to each other, and both fare worse than Trump. It’s important to note that none of these groups are official nor endorsed by the politicians themselves. They are grassroots forums made and utilized by everyday people. Reddit, too, reflects this trend. The #2 and #6 most popular subreddits on the entire site, judging by recent activity, are /r/The_Donald and /r/SandersforPresident, respectively. No other candidate has an active subreddit dedicated to them, at least not in the top 125.[7]

Of course, it must be also said that Bernie is most popular with young voters, and young voters are more likely to use Facebook than their older counterparts. This explains why his online supporter base is huge relative to other candidates’. This would also explain why his largest support group is called “Dank Meme Stash,” a phrase that means nothing to an older generation and everything to young people.

Still, the contents of each group are generally the same: heavily biased news sources that promise their candidate is winning, heavily biased articles against the competition, and of course, memes. These are the virtual trenches of populism in 2016. In these groups, tensions and fears are reinforced, and the feeling of moral superiority of one’s chosen candidate is impossible to avoid. These are average people linking up with other ordinary Americans to encourage support for the politician they feel will most represent them. It’s not about money. In fact, money can’t buy this kind of genuine, heartfelt publicity and sense of community surrounding the candidates’ political visions. The online forums dedicated to Sanders, in particular, place a huge emphasis on encouraging users to get out into the real world and campaign, canvas, donate, and make phone calls. They’ve had considerable success in getting people to participate.[8]

It’s unprecedented, and a strong contributing factor as to why these anti-establishment candidates have gained runaway success while old school politicians are left scratching their heads, attempting to artificially emulate the effect via their own social media pages.

If it weren’t for the massive ideological division in the country, one could envision social media being used to make the democratic process even more democratic. It’s beautiful, if you don’t look too closely, to see people share enthusiasm in the election and create a sense of community around their candidate of choice. But there’s a significant amount of hate in many of these online groups, particularly in groups dedicated to candidates whose platforms are based on discrimination and animosity. But even for followers of Sanders, who once prided himself on never running a negative campaign ad, hateful messages against other candidates cover the page and garner thousands of likes.[9] It’s difficult to see how this positive feedback loop of radicalizing ideologies will ever end; it seems impossible that the country will unite, or even become more moderate, in terms of ideology. This political gridlock in Washington, and this name-calling across the political spectrum, will likely not end until people can see each other’s point of view and find a compromise. Judging from social media, that day is very, very far away.

The people of America can agree on one thing: the political system isn’t doing its job and economic policies are failing the middle- and lower-classes. A new and intense brand of populism, magnified by social media and divided by ideological differences, has made the 2015-2016 primary season an unpredictable frenzy. Ultimately, it can be understood as two different groups of non-elite people whose visions of the future of America are at complete odds with one another. Global problems, like economic inequality, the fight against terrorism, and climate change, call for global cooperation, but domestically, the United States is failing to decide what role it will play in dealing with these crises. One thing is for sure: everyday Americans want to seize this country back from the elites who they believe are running it into the ground. However, only the future will tell which vision of America will prevail.

[4] Robert E. Scott, “Manufacturing Job Loss: Trade, Not Productivity, Is the Culprit,” Economic Policy Institute, August 11, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/manufacturing-job-loss-trade-not-productivity-is-the-culprit/.

[5] Michael Barthel, Elisa Shearer, Jeffrey Gottfried, and Amy Mitchell, “The Evolving Role of News on Twitter and Facebook,” July 14, 2015, http://www.journalism.org/2015/07/14/the-evolving-role-of-news-on-twitter-and-facebook/.

[7] Redditlist, accessed March 28th, 2016, http://redditlist.com/all.

[8] Bernie PB, accessed March 20th, 2016, https://www.berniepb.com.

[9] Arik Bjorn. Bernie Sanders Says, “I Have Never Run a Negative Political Ad in My Life!”. Video. 1:12. August 21, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gSFVJrgmUc4