What race should I be today?

This is what YouTuber, model, and makeup mogul Nikita Dragun “jokingly” asked her Twitter followers in response to her history of racial insensitivity. She has repeatedly tried to appear Black—one day her skin is pale, the next it’s dark. She has also worn box braids, twists, cornrows, and durags to sell this facade. As a result, Black people have accused her of blackfishing and appropriating Black culture.

Blackfishing is when a person alters their appearance through tanning, makeup, hair styling, and even cosmetic surgery to portray themselves as Black. It’s a form of cultural appropriation, as users steal from Black culture to achieve “Blackness.” In a 1945 essay, Professor Arthur E. Christy coined cultural appropriation as “the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.”

This sort of cultural appropriation gets confused with cultural exchange—cultures sharing their ideas, traditions, or knowledge. There is nothing wrong with exchange; in fact, it’s something to celebrate, as it unites people and combats insensitivity. However, appropriation is not exchange, nor does it increase understanding. As actress Amandla Stenberg explains, “appropriation occurs when a style leads to racist generalizations or stereotypes where it originated, but is deemed as high-fashion, cool, or funny when the privileged take it for themselves.”

I got one question….wtf? I’m not hating ❤️but I’m curious as to how you go from pale AS F*CK to a brown skin girl 😐@NikitaDragun #nikita #nikitadragun #dragons #blacktwitter #trans #MondayVibes #mondaythoughts #TikTok #Trending #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/phNv0RfHb8

— H0n3yEdits (@H0n3yE) September 14, 2020

Somehow, Dragun feigns ignorance and acts as though she is not purposefully appropriating Black culture. When a Twitter user accused her of blackfishing earlier this year, she replied that other races get tan. Later, she admitted that her complexion was not natural but insisted that she does get darker when under the sun.

Of course people tan. That’s not the problem, and Dragun knows that. The problem is that she spray tans and contours her face to appear Black. Worst of all, she promotes her merch and makeup lines shortly after each controversy.

Dragun’s “joke” reveals a blatant disregard for the Black people she hurts, and her “joke” showcases her willingness to mock them. Still, she acts innocent, even playing the victim to avoid scrutiny.

Dragun claimed that people have used her tan to invalidate her mixed Asian and Hispanic heritage. She explained that people would mock her skin tone and comment “she’s Hispanic today,” on pictures. She added that she does not have to pick a side. But people aren’t criticizing her for failing to pick a side or for appropriating Hispanic culture; they’re criticizing her for stealing Black style.

Dragun knows what blackfishing and cultural appropriation are. She acknowledged the double standard between Black and non-Black people when it comes to wearing Black hairstyles. In most states, schools and employers can ban natural hairstyles, which protect and maintain Black hair. In 2010, a Black woman named Chastity Jones had a job offer rescinded because she refused to cut her dreadlocks. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued on her behalf, lost, lost again on appeal, and was turned away by the Supreme Court.

In 2018, a Black girl was sent home from Christ the King Elementary School in Terrytown, Louisiana for wearing a braided hairstyle with extensions. The school cited its “natural hair” policy, which targets Black hairstyling. A year later, Boston’s Mystic Valley Regional Charter School gave two students detention, removed them from their sports teams, and barred them from attending prom—all for wearing box braids. The school claimed that allowing the “expensive” hairstyle would differentiate students based on socioeconomic status.

Box braids aren’t a status symbol, and their cost fluctuates. The braids can cost between $50 and $200 in Greater Boston and last up to three months; that price is within the same range as other hairstyles, including the perms and relaxers the girls previously used. But some people can braid their hair themselves or ask relatives to do it. Even the extensions can be cheap—as low as three dollars per pack. The school just used its policy to discriminate against Black students and control their hair.

While Black people face discrimination for their hair, Dragun can flaunt hers without hardship. Even though she’s not White, Dragun knows she’s more privileged than Black women. She’s claimed that her appropriation was appreciation—that she was trying to uplift and celebrate Black women. Instead, she paraded her privilege by taking advantage of Black culture and exhibiting blackface in its expanded modern form.

A Condensed History of Blackface

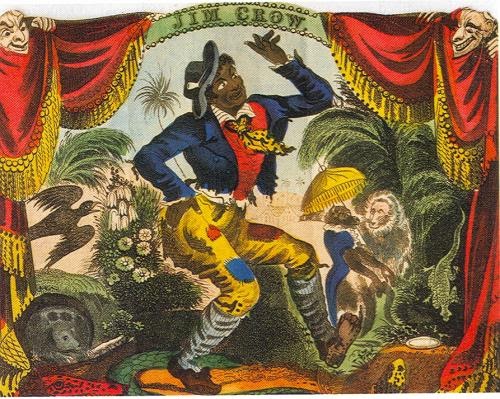

Dragun is a part of a larger conversation on blackface and its evolution. Blackface—“when people darken their skin with shoe polish, greasepaint or burnt cork and paint on enlarged lips and other exaggerated features”—originated in New York City during the 1830s. White performers would don woolly wigs and depict Black people as lazy, superstitious, and hypersexual.

Thomas Rice popularized it in 1928 through his character “Jim Crow.” As his show grew more popular, more performers depicted his character. Through minstrel shows—theatrical performances portraying racial stereotypes—White actors mocked, demeaned, and dehumanized Black people. Soon, Black people were wearing blackface and portraying harmful stereotypes in the same shows. Bert Williams was so successful that he became the highest-paid African American star in the world at that time.

Hollywood eagerly capitalized on blackface’s popularity. The Birth of a Nation—a 1915 Ku Klux Klan propaganda film—featured mostly White actors depicting Black men as sexual predators and simpletons. In 1936, Fred Astaire painted his entire body black for the film Swing Time; the director, studio, and distributors took no issue with it. Judy Garland donned blackface for Babes in Arms the same year she shot The Wizard of Oz.

While we're all talking about this, don't forget that the most famous and lucrative blackface character in history is MICKEY MOUSE. pic.twitter.com/LxuNBYlGUP

— Paul Waldman (@paulwaldman1) February 8, 2019

Animation also proved a fertile breeding ground for blackface; Professor Christopher P. Lehman noted that “American animation owes its existence to African Americans due to the prevalence of their negative depictions and caricatures in early cartoons.” Mickey Mouse’s origins allegedly stem from minstrel shows. Disney denies this connection, but the large painted mouth, white gloves, and song-and-dance numbers strike an eerie resemblance to minstrels. In Warner Brothers’ animation “Southern Fried Rabbit,” Bugs Bunny wears blackface to disguise himself as a slave.

Although blackface became less popular during the 1930s, filmmakers still incorporated it into their work. Some claimed it was justified as a part of “historical” pictures; they cited the 1943 film Dixie, which falsely claimed that minstrel shows emerged accidentally after a White actor with a black eye “covered his disfigurement in burnt cork.”

Even as blackface faded from the silver screen, it never really disappeared. It emerged at charity events and Greek life parties. It also remained common in comedies. The 1986 film Soul Man centered around a Harvard freshman darkening his skin to qualify for a scholarship. In the late 1990s, comedian Jimmy Kimmel wore blackface and spoke in a blaccent—an imitation of African American Vernacular English—to “poke fun” at NBA player Karl Malone. He also used the n-word repeatedly when mimicking Snoop Dogg. In 2013, Kimmel said that he prefers to portray Black people in his sketches.

Saturday Night Live has also played on blackface and Black stereotypes for laughs. In 1984, Billy Crystal used blackface to play singer Sammy Davis Jr., and in 2000 Jimmy Fallon used it to portray comedian Chris Rock. A year later, Darrell Hammond donned it to impersonate Jesse Jackson. Fred Armisen—who is part Venezuelan, Korean, and German—darkened his skin to portray President Obama multiple times.

The show also used Black actors to portray minstrel stereotypes. Eddie Murphy’s beloved impersonation of Buckwheat—a Black actor from the child troupe “The Little Rascals”—involves him mocking and exaggerating the actor’s accent. He makes this the butt of all his jokes.

Hollywood stereotyped Billie “Buckwheat” Thomas throughout his career; as a child, he was cast in films with horrible racial messaging. To see a Black man portray Buckwheat and further exaggerate these racist stereotypes is disgusting and heartbreaking. Thomas’s co-star in “The Little Rascals,” George McFarland, hated the impression since it came “at the expense of the people in his family.” Murphy’s portrayal is Black blackface.

Yet when Murphy hosted SNL and revived the character in 2019, he was generally praised. Buzzfeed’s Terry Carter Jr. included the impression when explaining why Murphy is “the GOAT.” Murphy even won his first Emmy for the episode. At best, the impression didn’t disqualify him; at worst, it’s part of why he won.

Last year, SNL had Leslie Jones portray Meghan Markle’s fictional third cousin—Shantay Thomas from the “Compton Thomases”—in the sketch “Etiquette Lessons.” Thomas wanted to visit England to see Markle’s newborn but was told that she needed etiquette classes. When the instructor meets Thomas, she quips that “this will be an experiment,” indicating that Thomas does not belong at the christening. Each time Thomas makes a mistake, the instructor mocks or physically assaults her. Besides stereotyping Thomas as uncultured, ill-mannered, and loud, the sketch proved extremely insensitive given the pervasive violence Black women face.

As people unearth more cases of blackface, only some perpetrators face backlash. Kimmel garnered more controversy than Armisen because he mocked Malone, while Armisen presented Obama as stoic and intelligent. Armisen’s mixed race and his less severe makeup also helped him evade scrutiny. As such, it appears that some actors get a pass so long as their intention is not to demean Black people.

The thing with Kim Kardashian and her family’s tireless history of cultural appropriation and Blackfishing is that she knows better. They know better. But they continue to do this because they know outrage sells. They’re able to keep their name relevant by doing things like THIS. https://t.co/rIE1fuYUXH

— Wanna (@WannasWorld) December 19, 2019

In a similar vein, those who appropriate Black culture do not always intend to demean Black people. When the average person appropriates Black culture, they’re following the trends that have normalized it. Celebrities, influencers, and fashion designers set these trends, blurring the lines between Black and American culture. Black people push to hold influential people accountable because they’re erasing Black culture.

These celebrities do not get to claim good intentions. Their actions harm the Black community—something Black people clarify every time the issue emerges. Nikita Dragun may say she’s not trying to offend Black people, but she uses outrage to promote her products. Likewise, Bhad Bhabie, the Kardashian–Jenners, and countless other celebrities do not get to act innocent while committing cultural appropriation; they purposefully fuel Black outrage for profit.

By appropriating “Blackness,” celebrities and creators flaunt their privilege and deprive Black people of opportunities. In 2017, makeup mogul Jeffree Star—whose past (and present) is riddled with racism—didn’t hire a Black model to promote his collection; he just made Dragun darker to achieve “representation.”

Niggita dragon is so fineeee 😫😫😫@NikitaDragun pic.twitter.com/XeeOvdNNtv

— Richard (@richardlaceyy) October 5, 2020

When influencers blackfish, they take space from Black people. Professor Alisha Gaines explains that these influencers “put themselves out there [as Black] and have all of these followers thinking they’re someone that they’re not.” They then curate entertainment through this “Blackness,” competing with those who are Black.

Furthermore, these influencers get sponsorships for being “Black.” Emma Hallberg, a Swedish Instagram influencer, built a brand off her glow—the highlight that reflects off her deep complexion. She amassed a huge following because of her pretty makeup, trendy clothes, and stylish hair. Many of her followers thought she was Black or mixed until an old, lighter-skinned photo surfaced.

I always like to use Emma Hallberg as an example of blackfishing. pic.twitter.com/aV8hHYDr6Z

— 🖤𝓣𝓲𝓯𝓯 (@returntheslab_) August 3, 2020

Her hair is straight, contrasting the usually curly or braided locks. Her lips are also thinner than they appear now, further replicating stereotypical Black features. Black people accused her of blackfishing, arguing she did so to gain sponsorships and brand deals.

The first Twitter user to call out Hallberg noted that “Black features sell but not on black people.” Hallberg used “Blackness” to advance her modeling career at the expense of Black models. It’s frustrating and insulting to see White women rewarded for stealing a culture that’s often disrespected and deemed inferior to European standards of beauty.

Sponsorships and brand deals should not go to people who pretend to be Black. Yet Hallberg still receives brand deals from companies looking to hire darker models. Pretty Little Thing and Fashion Nova sponsor her posts and cast her for modeling gigs, capitalizing off her blackfishing.

Fashion Nova in particular has used blackfishing models to market their products. YouTuber and makeup mogul Jackie Aina cut ties with Fashion Nova, noting that it markets to Black women without representing different skin tones on its social media. In particular, the company would hire racially ambiguous or lighter-skinned models as diversity tokens. This, coupled with their blackfishing models, reveals the company’s disregard for Black women. Companies that hire blackfishers are encouraging this behavior and emphasizing just how unwanted Black models are.

Cultural appropriation is robbery disguised as personal freedom. When non-Black people appropriate Black features and culture, Black people pay the price. We must watch as our culture is ripped from us. We must watch it get repackaged as American culture without any mention of its origins. We must watch as our opportunities go to appropriators. And we must watch silently because if we make a sound, our cries are deemed an infringement on their expression.

Beyond spreading this hurtful message, appropriation makes it harder for Black people to gain recognition for their culture. As Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor explains, “identity is partly shaped by recognition or its absence.” People suffer when their society illustrates a demeaning picture of them.

Non-recognition causes invisibility, where the marginalized community cannot relay what’s happening to it. When a community is invisible, outsiders misunderstand its culture, making it easier for them to steal it and pass it off as theirs. Appropriation can also confine a culture to stereotypes, affecting how outsiders view the community and causing marginalized people to view themselves as these stereotypes.

Darkening one’s skin for entertainment has always been disparaging. Problem is, it’s not just paint anymore.

The Spectrum

Blackface has always found new forms when the old ones become taboo.

The shift from mimicking features to mimicking skin tone supposedly aided proper imitation. Yet Kimmel and Fallon did not have to portray Malone and Rock—they chose to do it and saw no problem using blackface for comedy. SNL and its network, NBC, raised no objection either. It’s tiring how many celebrities have used imitation to excuse mockery.

It’s also tiring when White actors voice stereotyped Black characters. They’re mocking Black people through animated Black bodies. That’s blackface.

Take Cleveland Brown from Family Guy. Until recently, he was portrayed by White actor Mike Henry and was a token for the show to make racist jokes. In one episode, Cleveland’s wife didn’t want him hanging out with Peter, the White main character. Nevertheless, Peter meets with Cleveland behind her back, dressing as a cop to hide his identity. To maintain his cover, Peter assaults Cleveland with a baton. When mutual friend and actual policeman Joe arrives, he tells Peter to “save some for me” and joins him in brutalizing Cleveland.

Henry’s spin-off The Cleveland Show proved equally racist. As Professor John McWhorter explains, the show is “basically Family Guy in blackface.” The show’s creators didn’t even try to make Cleveland or his family interesting or distinguish them from other characters. Their race was the only thing that set them apart and made them worth watching.

Henry countered that “no one of color has had a problem with it”—a bold, uncorroborated assertion. Even more so, it’s not up to people of color to determine whether Cleveland is offensive. It’s up to Black people, and I say it’s offensive.

Henry added that most of the actors were African American. But it does not matter that the cast is Black when most of the writers aren’t. When writers’ rooms lack Black voices, they’re more likely to rely on Black stereotypes to drive character arcs. At best, these characters are stale; at worst, they’re inaccurate and offensive.

Blackface is most harmful in its purest, original form, but that does not excuse its other iterations. Yet celebrities always give flimsy justifications for harming our community. First it was “historical accuracy,” then it became an “imitation tool.” Now it’s “flattery,” “appreciation,” or “representation.”

I’m not flattered when Nikita Dragun, Kylie Jenner, or anyone else darkens their skin to look like me. I do not appreciate it when they take our culture without considering the harm that it causes. And I am not represented when someone creates and portrays a stereotyped version of me.

It’s not the end of the world when one non-Black person wears dreadlocks or darkens their skin. But it reminds me of the rights I do not have—my right to wear my hair however I please and my right to exist as a Black person in this country. When a White person repeatedly appropriates my culture, they normalize these practices. They swipe opportunities and prevent us from profiting off the culture we’ve built.

I am tired of giving celebrities and creators the benefit of the doubt. I am tired of hearing apologies unsupported by action. I am tired of people telling me that I am too sensitive or that I should not be offended. It’s gaslighting me and my community. It’s condescending when people try to explain what is happening to me when I am the one experiencing it.

When someone appropriates Black culture, Black people should be left to take charge of the conversation and state what needs to change. So the next time a celebrity does these things—because there will be a next time—Black voices must be centered and celebrated.

Instead of buying products from people and companies that appropriate Black culture, support Black-owned businesses. Donate to organizations dedicated to increasing Black representation across industries. Vote for candidates that will progress and protect civil rights. Be actively anti-racist and condemn all forms of blackface.

The appropriation of Black culture fuels racism against Black people, just as appropriation of Native American, Latin American, Islamic, and Asian cultures fuels bigotry against those communities. The dual cures of cultural awareness and sensitivity can only be used once the blackface comes off.

And it’s only by amplifying Black voices that non-Black people will grasp just how wide the blackface spectrum is.