Beheadings are unpleasant.

Not that a living person can confirm it, but it seems like an awful time.

For most of us, beheadings are not a daily concern. We worry about disappointing our bosses because we don’t want to be shouted at, demoted, or fired. But even in the worst-case scenario, we don’t presume we’ll lose our heads.

The same has not always been true for the Speaker of the House of Commons. In the 150 years following the appointment of Sir Thomas Hungerford as the inaugural Speaker, seven Speakers were relieved of their heads. Such was the punishment for relaying news from Parliament that displeased the monarch.

In April 2014, more than six centuries after Hungerford first assumed the chair, John Bercow did something Hungerford and his contemporaries would have thought unthinkable.

In front of Bercow (pronounced BURR–COE) stood David Cameron, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and—given the modern monarchy’s constitutionally paramount but practically symbolic place—the most powerful person in the country.

Cameron took a brief detour from the debate over privatizing Royal Mail to roast his biggest political rival, Leader of the Opposition Ed Miliband. Cameron mocked the appointment of David Axelrod, a former advisor to US President Barack Obama, to Miliband’s party’s campaign team. Cameron got as far as, “I don’t know what they’re paying him” before a bellow emanated from the Speaker’s chair.

“Order! Order! Order! Order! Order!” Bercow shouted.

“But I haven’t finished,” Cameron replied as his fellow Conservatives cheered him on. Bercow waited for the noise to subside.

“In response to that question,” he said, “the prime minister has finished, and he can take it from me that he’s finished.”

Cameron didn’t call for Bercow’s execution. Neither did the Queen. Not then, not in the five years since. The Speaker isn’t the monarch’s subservient messenger anymore. They uphold the House’s traditions, enforce its rules, and control its members.

Bercow has advocated for open democracy, upholding century-old traditions and reforming where appropriate. He’s helped guide the country through the maelstrom of Brexit. He’s faced intense and often unjustified criticism from the most powerful officials in the country.

And he’s quite possibly the most entertaining political figure on the face of the earth.

How it Works

The House of Commons traces its lineage to 1341 and, along with the House of Lords, comprises the Parliament of the United Kingdom. As the more powerful House, Commons wields immense power over policy, precedent, and political norms in a nation without a written constitution.

Though elements of its design derive from centuries-old tradition, the Commons chamber is just seventy-five years old. It was rebuilt in 1945 after being destroyed by the German Blitz in 1941.

The House comprises 650 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected by first-past-the-post voting. The majority party—or a coalition of parties constituting a majority—is called “the government” and dictates House business. The leader of the largest party becomes Prime Minister and appoints other party members to form the Cabinet. The largest non-government party becomes “the opposition,” with its leader designated “Leader of the Opposition.”

General elections are held every five years, though they can occur sooner. The government can call a snap election to try to strengthen its majority, while any MP can table a motion of no-confidence that, if successful, dissolves the government and forces an election.

When American voters hear “house Speaker,” they think of Nancy Pelosi, Paul Ryan, John Boehner, and Newt Gingrich. They think of political strategy, legislative maneuvering, and representing one’s political party to donors and the media.

If the Commons Speaker did any of those things, Parliament would fire them on the spot.

The Speaker is an MP voted into the office by the other MPs. Upon election, the Speaker resigns from their political party and is expected to remain politically impartial. This expectation has been the norm for nearly two centuries.

The Speaker does not vote in Parliament, meaning their constituency lacks representation. Because the major parties usually don’t oppose the Speaker in elections, their constituents have no voice in the legislature. The Speaker does not campaign on political issues, but stands only as “the Speaker seeking re-election.”

The Speaker votes only to break ties. These “casting votes” follow a two-centuries-old convention to vote for further debate or against bills, based on the principle that new laws should be created only by a majority and that the Speaker should not create that majority.

The Speaker ensures that the House functions appropriately. They moderate debates by attempting to keep the proceedings civil and orderly, and by upholding a litany of customs to ensure the same. They direct MPs to withdraw inappropriate remarks, quiet the House so MPs can be heard, and suspend MPs for repeated disorderly or disobedient conduct.

A Speaker’s demeanor in these job functions is a large determinant of their public image. Michael Martin, the Speaker before Bercow, had a subdued, quiet manner. Betty Boothroyd, Martin’s predecessor, was more of a loud disciplinarian.

Bercow’s demeanor is so thunderous, so scholarly, and so cartoonishly English that it’s made him into a full-blown meme.

Commons Cacophony

The House of Commons is a zoo.

MPs don’t keep their opinions to themselves for long. Clapping is banned in the chamber, so they shout “hear, hear” to indicate approval. These shouts typically devolve into indistinct shouting, with many MPs forgoing words entirely in favor of vague “eeeeaaaahhhh” noises.

The chamber’s topography exacerbates the chaos. It seats only about two-thirds of the 650 MPs, forcing many to stand. The government faces the opposition. During debates, MPs can’t cross the red lines painted in front of each bench. The lines were supposedly placed just over two sword lengths apart to prevent swordfighting, because anybody angry enough to run an opponent through with a rapier will be halted by the formidable sight of a red line.

Reasoned, civil debate in a zoo requires a capable zookeeper. Bercow chooses an MP to speak and ensures that the House hears them. This often requires quieting the other MPs, something he has done emphatically, distinctively, and hilariously.

And it all starts with one word: order. Bercow screams it whenever MPs need quieting down. If you’re wondering how one word can elevate a supposedly boring parliamentary official to a YouTube phenomenon, watch this video. Or this one. Or this one. He proclaims the word with such force, gusto, and conviction that he’s turned the word into an art form. It’s landed him on T-shirts, mugs, and posters. It’s been remixed again and again and again. When his wife Sally polled Twitter users in 2010 to name the family’s new cat, “Order” won out. He even provided a helpful explanation on a late-night talk show regarding which style of “order” he uses for different scenarios.

But one word alone doesn’t encompass his entertainment value. His quips when quieting MPs are legendary, particularly outside the UK, where observers often view him as a British caricature. This is best encapsulated in a compilation on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver titled “The Very British Put-Downs of Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow.”

“You were much better behaved when you were at Oxford University!” he bellowed at a particularly loud MP. “What’s happened to you, man?”

“Mr. MacNeil,” he cooed to another. “Mr. Angus Brendan MacNeil. Calm yourself! You may be a cheeky chappy but you’re also an exceptionally noisy one.”

“The honourable gentleman has got to learn the art of patience,” he said in a particularly viral soundbite. “And if he is patient, if he deploys zen, he will find that it is ultimately to everybody’s advantage.”

It’s worth stopping a moment to explain the “honourable gentleman” bit. Commons may be a zoo, but it overflows with the traditional British courtesy you’d expect of a body named, in full, “The Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Parliament Assembled.” (The House of Lords’ full name is even more ridiculous).

MPs refer to each other not with the second-person “you,” but in the third-person, with “the honourable gentleman/lady,” occasionally adding the member’s constituency after the address. “Right honourable” is used for senior members. Members address the Speaker during debates instead of each other.

Bercow’s style is perfect for such a formal, raucous place. As one MP told the New York Times in 2013, “It’s as if he goes to bed every night, reads a thesaurus, inwardly digests it, and then spews it out the next day.”

Bercow reprimands MPs not for interrupting while sitting, but for “chuntering from a sedentary position.” They don’t rant, they “prate” and “cavil.” They don’t take medicine; they take “medicaments.” Assiduous, jocular, and perspicacious members must handle matters with alacrity, lest Bercow deprecate their actions. He delivers this erudite vocabulary so quickly, so smoothly, and so off-the-cuff that it almost defies belief.

The same British accent that lends authority and gravitas to characters on the screen and stage makes Commons proceedings engagingly goofy at times. In March, Bercow told Die Welt that he thought people were interested in “British eccentricity.”

“It’s not a performance. It’s not an act,” he said. “I love speaking and speak rather too much, no doubt.

“The way I speak is the way I’ve spoken since I was a kid. I inherited my speaking style from my father who tended to speak in paragraphs . . . I was quite a small boy and there were bigger boys around me. They used their fists; I used words.”

He also spoke to his occasional injections of levity.

“I think it is better to try to handle things with a degree of humour, if possible, rather than everything being deadly serious,” he remarked. “It’s not a performance. It is a serious business, but a bit of humour, a bit of lightness of touch, a bit of laughter now and again is not a bad thing. In a conflict situation, a situation of high tension, a situation of loss of tempers, if I can calm it down by saying something a little gentle, why not?”

That explains the moments when his reprimands extend past noisiness to the outright joking. He told off one MP who interjected “ahoy there” while he spoke, and offered an almost comically British response to another who wished him a “Happy Kiss-a-Ginger Day.”

“This kiss-a-ginger activity is probably perfectly lawful, but I have no plans to partake of it myself,” he said to raucous laughter from MPs. “Strikes me as a very rum business altogether. As colleagues can probably tell, I had no idea about what the honorable gentleman was prating. The matter had to be Googled for me.”

He frequently roasts MPs when their soccer teams lose to Bercow’s beloved Arsenal. He interrupted a debate about the UK’s trade relationship with Switzerland to remark “that £32 billion volume of trade with Switzerland is very important, but . . . the best thing about Switzerland is Roger Federer.” He even complimented an MP’s baby who was watching from the visitor gallery.

“For all the turbulence and discord of today’s proceedings, the little baby who has been observing them has been a model of impeccable behavior,” he said to applause from the House. “We salute that. The future of our democracy and the future of our country.”

Watch Bercow enough and you’ll see that, despite the instances of him calling an MP an “incorrigible delinquent,” “overexcitable individual,” “exceptionally boisterous fellow,” and telling them to take their medicaments or yoga classes, he respects his colleagues and wants what’s best for the House.

Bercow has never been shy about doing what he considers best for the House. Even when it involves clashing with the nation’s most powerful people.

The Times They Are A Changin’

The House of Commons predates European colonialism and widespread acceptance of the heliocentric model. As such, members are sticklers for tradition. Bercow is charged with upholding that tradition.

But he’s also reformed plenty, tweaking parliamentary procedure to make leaders more accountable to the legislature and, in turn, the people.

Bercow assumed the Speaker’s chair in June 2009 as Parliament was mired in scandal. MPs had abused their allowances and expenses, particularly regarding their second homes in London. The scandal forced the resignation of the previous Speaker and shook public confidence in Parliament.

Bercow wanted to strengthen the institution of Parliament. In a speech he gave while campaigning for the Speakership, he argued for empowering backbenchers—MPs who are not ministers or opposition spokespeople (American equivalent is “rank and file”). He thought it would revive Parliament as a whole. He’s maintained that stance in the decade since.

“[It’s about] helping Parliament get off its knees and recognize that it isn’t just there as a rubber-stamping operation for the government of the day,” he told the BBC in 2012. “And, as necessary and appropriate, to contradict and expose the government of the day.”

“I will strive to ensure that all parts of the House are heard fully and fairly,” he asserted in a speech before his unanimous re-election in 2017. “And, as always, I will champion the right of backbenchers to question to probe, to scrutinize, and to hold to account the government of the day.”

The functionality of a parliamentary democracy is guaranteed by the government’s majority in the lower house. The government chooses debate topics and schedules votes on the bills it proposes. Party whips ensure tight party unity and lockstep voting on major issues. Empowering backbenchers—particularly by letting them take over the House’s business, as Bercow did during Brexit deliberations earlier this year—is a considerable break with tradition.

Urgent questions (UQs) have been a significant component of Bercow’s reform. MPs submit UQs to the Speaker; if the Speaker accepts them, the relevant government minister is compelled to appear in the chamber—without notice—to answer for the government on the issue at hand.

Before Bercow, UQs were infrequent. His predecessor allowed forty-two UQs in the last five years of his Speakership; Bercow granted 159 in the first five years of his. Bercow extolled its benefits in a 2013 speech, arguing that government ministers more readily give statements now because they know a UQ is likely if they don’t.

“The UQ, like so many weapons which the House theoretically had at its command to train on the executive, had become so rusty that it was no longer credible to seek to pull the trigger,” he said. “They have now become an established element in the parliamentary timetable, that they have forced the House of Commons back onto the news pages and to the airwaves.

“I am sure that my successors will do things very differently to me and rightly so, but I would be amazed if they put the Urgent Question back into parliamentary cold storage.”

His accountability reforms have extended to even the most senior ministers. Former Prime Minister Theresa May was kept in the chamber for up to three hours during statements as Bercow gave every backbencher wanting to speak the chance to do so.

“I was particularly concerned that ministers should be accountable first and foremost to Parliament,” he told the BBC in 2012. “Their upset, their irritation, their inconvenience cannot be the concern of the Speaker.”

Not that this is the only way in which Bercow’s reforms have irked the Prime Minister.

If Commons is a zoo, Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs) is putting all the animals in the same cage. Every Wednesday at noon, the Prime Minister visits the House and answers questions from MPs for about half an hour. At its best, PMQs sees opposition MPs holding the Prime Minister and the government to account. At its worst, it’s an absolute mess.

The House of Commons chamber filled past seating capacity at Prime Minister’s Question.

A 2014 report by the Hansard Society found that a plurality of voters considered PMQs “noisy and aggressive” and thought that MPs didn’t behave professionally. While it was the parliamentary event voters were most aware of, two-thirds thought it involved too much political point-scoring and a minority considered it relevant and informative.

Bercow agreed. After the report was published, he wrote a letter to the leaders of the three largest political parties asking them to “cut out the orchestrated barracking.” He said he didn’t expect MPs to act like “Trappist monks,” but complained of “yobbery and public school twittishness” and criticized party whips who were orchestrating “walls of noise.”

“I cannot think of any business that puts its worst product in the shop window, and in some respects [PMQs] is our worst product,” he told the Guardian in 2011. “I think the level of heckling, the extent of catcalling, the sheer decibel level, are not conducive to reasoned debate.”

“When the decibel level exceeds anything that Deep Purple would have dreamed of in their heyday,” he quipped in 2013. “That is a negative.”

Bercow also increased the number of questions asked during PMQs, further drawing the ire of the executive.

His reforms extend to himself. Bercow abandoned the traditional wig and court dress in favor of a simple black gown over his suit (and quirky, colorful ties).

“I do not believe we will recover public respect for politicians and for Parliament by wrapping ourselves in very very very traditional and elaborate costume,” he remarked shortly after his election in 2009. “It’s not about me and what I like or dislike; it is about the institution.”

Every break with tradition has been met with controversy. The Conservatives, who have been in power for nine of Bercow’s ten years in the chair, have generally seethed at his reforms, while the Labour Party has rejoiced at their new empowerment to question and probe the government.

Bercow best summed up his aims in 2011, when Rupert Murdoch’s testimony in the wake of the News Corp phone hacking scandal tested Parliament’s ability to compel and punish witnesses.

“Parliament has started to reassert itself,” he stated proudly. “We have rediscovered our collective balls.”

Bias and Bullying

On February 6, 2017, the opposition side of the House cheered (which they do often) and clapped (which is forbidden) while the government side sat motionless. John Bercow had, depending on who you asked, either defiled his office or stood up for the House’s values.

Bercow, UK First Secretary of State William Hague, and US Secretary of State John Kerry stand by the chamber’s despatch box in 2013.

The election of Donald Trump forced Americans to reckon with their democratic and sociopolitical values. But theirs was not the only reckoning. America’s allies, and key officials within them, were forced to consider their positions.

A Labour MP raised a point of order regarding objections to the newly inaugurated President Trump speaking to both Houses of Parliament in Westminster Hall. Bercow explained that such an address by a foreign leader was an earned honor, not an automatic right. He clarified that he was one of three “keyholders” who, by consensus, determined when the Hall could be used for an address. Then he dropped a bombshell.

“Before the imposition of the migrant ban,” he said, referring to Trump’s executive order banning immigrants and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US, “I would myself have been strongly opposed to an address by President Trump in Westminster Hall. After the imposition of the migrant ban by President Trump, I am even more strongly opposed to an address by President Trump in Westminster Hall.”

After adding that he wouldn’t extend Trump an invitation to speak in the Royal Gallery either, Bercow concluded with his rationale.

“As far as this place is concerned,” he said. “I feel very strongly that our opposition to racism and to sexism, and our support for equality before the law and an independent judiciary are hugely important considerations in the House of Commons.”

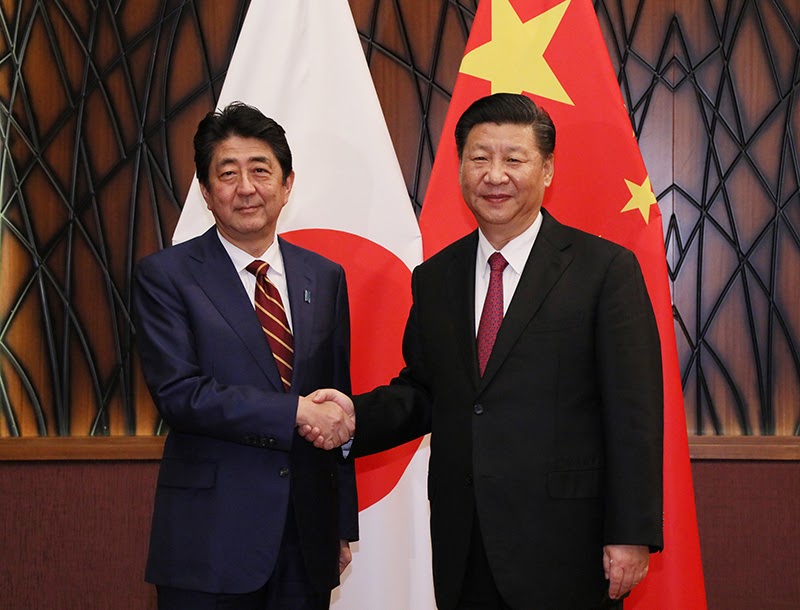

Conservative MPs accused Bercow of grandstanding, of hypocrisy (he didn’t object to Xi Jinping’s address), and, most importantly, of violating the central tenet of his office: impartiality.

It wasn’t the first time the Tories (Conservatives) questioned his biases. In his youth, commentators described Bercow as a “right-wing radical,” but as his career progressed, he gradually shifted from the right wing of the Conservative Party to its left wing. In the years before his election as Speaker, many Tories suspected he would defect to the center-left Labour Party.

When Bercow assumed the chair in 2009, he did so with little support from his party. Conservative MPs and papers denounced him for perceived bias toward Labour right from the start. But the appearance that his reforms targeted the Conservative Party was not a function of bias. The Tories held power for most of Bercow’s speakership, so his reforms holding the government to account entailed holding Tories to account.

Bercow’s ideological shift was due to a change of conscience and his wife’s influence. Sally Bercow attracted fierce criticism during her husband’s Speakership for her vocal support of the Labour Party, which some argued compromised her husband’s impartiality. These tensions came to a head in the chamber in January, when MPs questioned Bercow over a “Bollocks to Brexit” sticker in the windshield of his wife’s car. Sally Bercow has always defended her right to speak her mind. Her husband backed her up, saying, “she is entitled to her views.”

These complaints—and the complaints that Sally’s frequent tabloid appearances and provocative social media comments degrade her husband’s dignified office—range from ridiculous to sexist. The bullying allegations against Bercow are far more worrisome.

In 2018, Kate Emms and Angus Sinclair, two of Bercow’s former secretaries, alleged that Bercow bullied them. Sinclair accused Bercow of undermining him in front of other staff, using foul language, and smashing a mobile phone on his desk. Bercow denied the allegations.

Dozens of other staff had accused other MPs of bullying, sexual harassment, and workplace mistreatment, and there was an ongoing investigation led by English High Court Judge Dame Laura Cox. Because Cox was not tasked with investigating individual complaints, including those against Bercow, there was no ruling on their veracity.

Cox did find a tradition of “deference and silence” that “actively sought to cover up abusive conduct” and “didn’t protect those reporting sexual harassment or bullying.” She asserted that the Commons senior leadership, including the Speaker, was incapable of changing the culture.

The aftermath was messy. The Commons Select Committee on Standards voted 3–2 to not formally investigate the claims against Bercow. The Speaker wanted an independent body to examine future cases. Some MPs—mostly Tories—called for Bercow to resign after the Cox inquiry. Others—mostly opposition members—criticized the accusers for politicizing the inquiry. By and large, backbenchers backed Bercow because they felt empowered by his reforms, Labour MPs thought he was better for their Brexit goals, and some MPs felt it was unwise to change Speakers amid the Brexit debacle.

Some MPs tried to take the decision out of his hands. In April, Conservative MP Crispin Blunt, citing what he considered Bercow’s failure to remain impartial, began collecting signatures for a no-confidence motion in the Speaker. He said he’d introduce it only if he received one hundred signatures, as he feared retribution from Bercow. Though he claimed he had support from some government frontbenchers (ministers), he never tabled the motion. Another effort in 2017 collected a few signatures, but fizzled.

An attempt in 2015 garnered the most support. Outgoing Leader of the House William Hague and government Chief Whip Michael Gove motioned to elect the Speaker by secret ballot in the next Parliament, making Bercow’s removal more likely.

It was a dirty move, and MPs on all sides criticized it as such. The vote occurred on the last day of the parliamentary session, at the last minute, with virtually no notice. Labour MPs and some Tories complained of not being notified, and many Labour MPs supportive of Bercow did not know about the vote and were absent. The Tories imposed a three-line whip, meaning that Conservatives who voted in Bercow’s favor risked expulsion from the party. Prime Minister David Cameron returned from Coventry to attend the vote. At a party meeting before the vote, Tory MPs were reminded that it was William Hague’s birthday and he deserved a win.

Charles Walker, a Tory MP and the head of the Procedure Committee (the relevant Commons body on this issue) was among those not informed. During the debate, an emotional Walker said, “I have been played as a fool, and when I go home tonight I will look in the mirror and see an honorable fool staring back at me, and I would much rather be an honourable fool in this, and any other matter, than a clever man.”

The motion failed, 228–202. Enough Tory backbenchers defected that, even with the surprise nature of the vote, Bercow kept his job. Bercow fought back tears as the result was announced; when it was, Labour MPs erupted into the sort of roaring applause that is usually forbidden in the chamber.

Government frontbenchers didn’t like Bercow then. They despise him now.

Brexit

On June 23, 2016, the people of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union (EU). With 72 percent of eligible voters casting a ballot, 52 percent voted to leave and 48 percent voted to remain.

The EU is an economic and political union comprising twenty-eight European states and roughly 513 million people. People, capital, goods, and services move freely within an internal single market according to laws agreed upon by member states. States have common trade, agriculture, fisheries, and regional development policies. Border controls are abolished, allowing EU citizens to live and work in different countries.

On March 29, 2017, the UK officially notified the EU of its intent to leave. The withdrawal date, originally set for March 29, 2019, was delayed to October 31, then to January 31. The government must negotiate an agreement with the EU and pass that deal through Parliament by the withdrawal date. Failing to do so results in a no-deal Brexit, which the Bank of England projects would shrink GDP more than five percent and more than double unemployment and inflation. Brexit also calls into question whether Scotland and Northern Ireland—which both voted to remain—will continue as part of the UK.

A month before the UK triggered Article 50, Bercow told students at Reading University that he voted to remain in the EU.

“We’re in a world of power blocs,” he explained. “For all the weaknesses and deficiencies of the European Union, it’s better to be a part of that big power bloc in the world than thinking you can act as effectively on your own.”

It didn’t matter that Theresa May and most MPs also voted to remain. It didn’t matter that Bercow’s opinion was measured and reasonable. The man who’s supposed to remain impartial was widely panned, and fairly so, for discussing his opinion on the nation’s hottest political issue.

Every procedural decision he’s made on Brexit since has been viewed through the filter of opinion. While it’s fair to consider his professed opinion, the widespread assumption that he tried to foil Brexit is shaky at best and institutionally destructive at worst.

Tensions rose this past January. The government proposed a motion in neutral terms, a common maneuver for introducing debates and votes, and one usually considered unamendable. Conservative MP Dominic Grieve tried anyway, proposing an amendment requiring the government—if it lost the EU withdrawal agreement vote—to return with a Brexit Plan B in three days instead of twenty-one. Bercow, supposedly without precedent, allowed the amendment.

MPs debated Bercow’s decision for an hour. Some MPs sought to clarify and understand Bercow’s decision, others sought only to make the same tired arguments over and over. Bercow, usually a fearsome debater, didn’t do himself many favors. He ducked questions, instead speaking in general terms about his job responsibilities. When MPs cited his responsibility to maintain precedent, he replied that he wasn’t obligated to do so, adding that “Precedent does not completely bind . . . if we were guided only by precedent, manifestly nothing in our procedures would ever change; things do change.”

He was criticized in the chamber. News outlets picked up where Brexiteer MPs left off, with some referring to Bercow as an “egotistical preening popinjay” engaging in “an act of Brexit-sabotaging skulduggery.”

But Bercow was in the right for two reasons.

Normally, Standing Order 24B forbids amending motions in neutral terms. But a month earlier, Grieve proposed—and Parliament passed, 321–299—an amendment exempting EU withdrawal motions from the standing order. It was a substantial move that allowed backbenchers greater sway over Brexit business. Because the Plan B amendment had to do with the withdrawal agreement, it was allowable.

Bercow also could have defended himself by citing a government statement from the previous June clarifying that it was the Speaker’s job to decide whether a Brexit-related motion is cast in neutral terms or not, and therefore whether it is amendable. Why Bercow didn’t use these justifications to defend his decision is a mystery, but the idea that he broke with procedure is false.

Commons passed the Plan B amendment, 308–297. When the government lost the withdrawal agreement vote, Grieve’s amendment took effect. All it did was limit Theresa May’s ability to run out the clock and use the impending Brexit deadline as leverage to muster support for her deal. The government seethed nonetheless.

If they thought they were mad then, it was nothing compared to the next big Brexit battle with the Speaker.

On March 18, Bercow addressed rumors that the government would have another vote on the withdrawal agreement the House had already rejected. Bercow cited Erskine May (the 1,300-page volume of parliamentary precedent), which says that motions and amendments that the House has voted on cannot be brought forward again during the same parliamentary session. Whether a motion or amendment is the same as a previous one is a matter for the Speaker’s judgment.

“It is a necessary rule to ensure the sensible use of the House’s time and proper respect for the decisions that it takes,” Bercow explained. “Decisions of the House matter. They have weight.”

The House had voted twice on the withdrawal agreement by March 18. Bercow said the second vote was permissible because the second agreement “contained a number of [binding] legal changes” negotiated with the EU. If another vote on the withdrawal agreement was to happen, Bercow said, changes to the agreement must be made.

Accusations that Bercow was trying to stop Brexit ran amok. It’s easy to blame the referee of a disorganized game, but the notion that Bercow is a Brexit obstacle on par with a hung Parliament and stagnant EU negotiations is patently ridiculous.

The EU’s negotiating stance has caused massive problems for British negotiators. With anti-globalist sentiment rising in Europe, the EU knows that giving the UK a sweetheart exit deal could encourage other countries to leave. After May negotiated changes to the first deal, EU leaders clarified that no further changes would be made.

But the hung Parliament is an even greater obstacle. May’s first deal was defeated 432–202 in January, the largest parliamentary defeat in the democratic era. May renegotiated with the EU, and her second deal was trounced 391–242 in March. Bercow made his ruling a week later, and when May brought a changed deal for a third vote on March 29, it failed 344–286.

These defeats are so irregular because the Westminster system of government is designed to run smoothly. Since the government usually has a majority, the Prime Minister can typically pass whatever legislation they want.

The Conservatives had a majority after the 2015 general election. Strong polling persuaded May to call a snap election in 2017, but lackluster campaigning resulted in a thirteen-seat Conservative loss and a thirty-seat Labour gain. The Conservatives formed a minority government via a confidence-and-supply agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Under this arrangement, the DUP votes with the government only on votes that would dissolve the government; they vote how they please on other issues.

May stayed in power, but the government has paid for their 2017 election losses in every Brexit vote since. Tory backbenchers have taken advantage of the chaos to introduce amendments and influence the House’s deliberations in a way they might not if the government had a majority. So-called meaningful votes on Brexit (as opposed to non-binding indicative votes) have failed. Amendments that the government dislikes—including Grieve’s—have passed. The Speaker’s role becomes more important in a hung Parliament, and Bercow has generally given preference to amendments that command cross-party support.

The government is bending to please different ideological factions in the House, something it wouldn’t have to do if it had a majority. It is not Bercow’s fault that the government can’t please UK citizens, Brexiteer MPs, and the EU all at once.

Yet the government’s snipes at Bercow became childish. In May 2018, Leader of the House Andrea Leadsom accused Bercow of calling her a stupid woman—trivial to Americans in the Trump era, but a big deal in the Commons given their conduct standards. Bercow clarified that he used the word “stupid” to describe the government’s scheduling of a major statement on a day reserved for opposition parties to control the House’s business. Even after he assured the House that it was not directed at Leadsom, she brought it up again seven months later as tensions between the Speaker and the government were building. Bercow’s explanation was reasonable and Leadsom knew better; it was a purely political move.

(Leadsom resigned her position in May when the prime minister proposed Brexit votes that Leadsom didn’t agree with. Her replacement, Jacob Rees-Mogg, is so known for his conservative ideology, traditionalist attitudes, and posh mannerisms that many in UK politics call him “the Honourable Member for the 18th Century”).

The government is also pondering lifelong consequences for Bercow. Normally, the government grants the Speaker a peerage when they retire, which allows the former Speaker to sit in the House of Lords for life. Such is the government’s animosity toward Bercow that he could become the first Speaker in more than two centuries to not receive one. When he took the chair a peerage was a foregone conclusion; now nobody is really sure if he’ll be in the House of Lords.

MPs and commentators decry Bercow’s actions and supposed attempts to halt Brexit without actually linking the two. If Bercow had done everything the Conservatives wanted, the government’s Brexit efforts would likely be stuck exactly where they are now. Despite the best efforts of the prime minister, the cabinet, and party whips, the Conservatives weren’t united during any of the withdrawal agreement votes. After the first, and worst, loss, May’s government barely survived a no-confidence vote tabled by Opposition Leader Jeremy Corbyn.

It’s no shock that Brexit threatens Bercow. It has, after all, forced the resignations of two Prime Ministers (David Cameron and Theresa May) and many of their subordinate ministers. Tories can scream about the Grieve amendment all they want, but as long as selecting amendments is part of the Speaker’s job there will always be a bit of bias. Not every amendment can be debated and voted on; someone has to choose which ones to table. Bercow indicated that his motive with Grieve’s amendment was to empower a majority when the government didn’t have one.

With the Brexit referendum, the people of the United Kingdom—knowingly or not—elected to place their economy on the edge of a cliff. If they exit without a deal, they will have thrown themselves off. As authoritarianism, anti-globalism, and populism gain momentum around the world, one of the UK’s most visible, powerful political figures is expected to have no political opinions.

It’s a dynamic so outrageous that the country’s government and media almost cannot fathom that it might be true.

What’s Next?

On August 22, 2018, Boris Johnson, to nobody’s surprise, said something offensive.

He was attacking Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry for asking whether the government would take Russia to court over the poisoning of Russian agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter on British soil. In doing so, he called her “Lady Nugee.” Thornberry is married to Sir Christopher Nugee, a judge of the High Court of England and Wales, but uses her maiden name.

“We don’t name-call in this chamber . . . we do not address people by the titles of their spouses,” Bercow said to Johnson. “It is inappropriate and frankly sexist to speak in those terms, and I’m not having it in this chamber. That is the end of the matter. No matter how senior a member, that parlance is not legitimate, it will not be allowed, and it will be called out . . . I hope I have made the position extremely clear to people who are not well-informed about such matters.”

Almost a year later, Theresa May resigned as Prime Minister. Queen Elizabeth II asked Johnson—the winner of the Conservative Party’s leadership election—to form a new government. Johnson accepted.

The changing of the guard didn’t change the government’s problems in delivering Brexit. The only thing that changed was Johnson’s undemocratic approach. He tried to prorogue (suspend) Parliament for five weeks in the run-up to the deadline to limit the House’s deliberation time. The prorogation lasted just seventeen days before the UK Supreme Court ruled it unlawful, citing circumstances that “have never arisen before and are unlikely to arise again.”

The move was widely decried as an executive power grab. Bercow, who once said the idea of the government forcing through a no-deal Brexit without Parliament having a say was “for the birds,” agreed. He criticized the decision as a “constitutional outrage” that he would “fight with every breath in [his] body.” He rejoiced at the court ruling that affirmed democratic norms.

Though Johnson’s power grab was arguably the Tory government’s most blatant, it was not its first. Many commentators have argued that the government has circumvented Parliament in Brexit-related matters and that Bercow was defending the power of the legislature against “the overweening power of the executive [and] prime ministerial fiat.” Brexit is the most consequential British political decision of this generation, and a minority government is bullying the legislature.

Passing the deal through Parliament also got harder. The Conservatives’ arrangement with the DUP gave them a working majority of one. They lost that majority on September 3, when Conservative MP Philip Lee defected to the Liberal Democrats in the middle of Johnson’s speech.

Amid all the chaos, the long-awaited hammer finally dropped. On October 31, just two days after the House voted to have an election on December 12, John Bercow retired from Parliament. On November 4, the House chose Sir Lindsay Hoyle, senior Deputy Speaker for most of Bercow’s tenure, as the new Speaker. Much like the transition from May to Johnson, the Speaker swap will not change the underlying problems the office-holder faces.

Bercow’s performance in his last weeks was exactly what his biggest overseas fans had hoped for, particularly during one debate in September.

“I say to the Chancellor of the Duchy,” he shouted at longtime target Michael Gove. “When he turns up at our children’s school as a parent, he’s a very well-behaved fellow . . . Don’t gesticulate! Don’t rant! Spare us the theatrics! Behave yourself! BE A GOOD BOY, YOUNG MAN! BE A GOOD BOY!”

John Oliver, who once aired a segment about Bercow’s “Very British Put-downs,” aired another called “Ahead of his retirement, a look at Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow, who only ever wanted one thing.” It was a compilation of Bercow bellowing the single word that launched him to internet immortality, the word that he said almost fourteen thousand times as Speaker.

John Bercow’s legacy is not an easy one, and he is far from blameless. But beneath the ego and pompous putdowns is a man who loves democracy, who devoted his life and voice to it, and who stood up to powerful people in turbulent times. It’s worth reflecting on the values he championed, and whether the centuries-old idea of the impartial Speaker can survive.