“In a slum outside the grand old city of Lahore, a woman named Saima Muhammad used to dissolve into tears every evening. Saima had barely a rupee, and her deadbeat husband was unemployed and frustrated and angry. He coped by beating Saima each afternoon. Their house was falling apart, and Saima had to send her young daughter to live with an aunt, because there wasn’t enough food to go around. “I had an awful life,” recalls Saima. Then when Saima’s second child was born and turned out to be a girl as well, her mother-in-law told Saima’s husband, in front of her, “So you should marry again. Take a second wife. It was at that point that Saima signed up with the Kashf Foundation, a Pakistani microfinance organization that lends small amounts of money to poor women to allow them to start a business. Saima took out a $65 loan and used the money to buy beads and cloth, which she transformed into beautiful embroidery that she then sold to merchants in the markets of Lahore. She used the profit to buy more beads and cloth, and soon she had an embroidery business and was earning a solid income – the only one in her household to do so.”[1]

The story of Saima Muhammad’s escape from poverty is typical of thousands of microfinance clients across the globe.

It’s the story of how microfinance institutions such as Pakistan’s Kashf Foundation can financially empower impoverished individuals to elevate themselves and their families out of extreme poverty, thereby creating a near miraculous intersection of free market economics and humanitarianism.

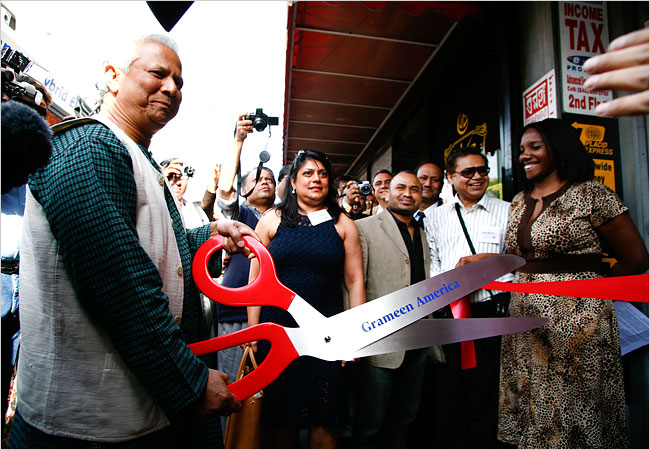

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) like Kashf were founded in response to early successful microfinance ventures like Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank, when international agencies began prioritizing the development of microfinance sectors as a key twenty-first century development goal. With over 10,000 MFIs currently in operation, the microfinance industry has expanded from a budding global development vision to a lynchpin of developing economies across the globe today.[2] Yet the sudden ubiquity of MFIs raises several key questions about the new era of microfinance: How similar is this new generation of MFIs to the “ideals” set by groups like Grameen? Is Saima’s sustained success with microcredit typical of this new generation of MFIs’ clientele?

As Dr. Tyler Wry of the Wharton School reveals in his recent working paper, the current state of microfinance is concerning, with the new era of increasingly commercialized MFIs deviating from their ideal social mission.[3] Wry links this trend to a generation of flawed policy-making from international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank, who have approached the issue of creating MFIs as an urgent question of purely impersonal free market forces, thereby ignoring the important sociological context of micro banking services.

Wry explains that microfinance, at its core, is a type of business. Thus, MFIs are governed by the same laws as businesses: liberalized markets with free cash flow and deregulation for easy foreign investments lead to increased business founding, so these same market conditions should lead to the development of the microfinance sectors in various countries — and they do. However, for any business, market conditions are not the only factors at play: all industries attempting to break into a new country’s market obey the laws of a sociological principle called “logics.”

Logics are a shared framework of thinking amongst a population that can be used to predict consumer and state behavior. A new industry succeeds in a country when it matches, or “conforms” to the prevalent existing logic, whereas industries that violate the nation’s logics — that contradict known social norms and values of a people — often fail to acquire the necessary resources for success. Thus, the challenge facing microfinance leaders today is how to receive institutional support for an MFI, while still serving the members of a population who have been systematically cut off from traditional financial channels. For example, though Saima’s case illustrates the potential impact of MFIs operating in nations with powerful patriarchal logics, the inherent nature of microfinance disrupts traditional gender norms so fundamentally that MFIs operating in patriarchal nations often fail to acquire the necessary resources for continued operation. In other words, the features of a society that demand the presence of MFIs are precisely what can inhibit the institution’s success there. Pakistan (along with a handful of other nations) uniquely escapes this fundamental paradox by subsidizing MFIs through the State Bank of Pakistan, while still having a profoundly high gender inequality index.[6][7]

The flaw of modern microfinance occurs because international agencies have sought to remedy the “logic” paradox through neoliberal economic policies, as a business-friendly environment should somewhat compensate for the lack of resources caused by patriarchal limitations. And it does; in terms of the creation of MFIs. But this new generation of microfinance institutions — the ones bred in a neoliberal marketplace — are naturally more likely to be for-profit organizations. All efficient MFIs must attempt to reach partial profitability; however, the postmodern, increasingly commercialized era of microfinance has been dominated by the creation of publicly traded institutions with a responsibility to shareholders. Pakistan’s logic-defying society, possessing both a need for MFIs and a society willing and capable of supporting microfinance, is anomalous to the overall trend of developing nations’ attitudes towards emerging microfinance sectors.

In 2007, Mexico’s Compartamos Banco’s massively successful IPO made it the first microfinance bank in Latin America to become publicly traded. In 2011, India’s SKS Microfinance, the largest MFI in the nation raised a grand total of $358 million in its massively successful IPO.[4]

Though Compartamos no longer considers itself a microfinance firm, and SKS’s founder resigned in disgrace after initial scrutiny, there are myriad, similarly structured for-profit MFIs still in operation. These groups flaunt their earnings as proof of hyper-efficiency in the new age of microfinance — a natural and necessary progression in the industry’s evolution.[5] However, the for-profit model of micro banking services ultimately decreases the immense social impact of the Grameen ideal. For instance, a responsibility to shareholders pressures for-profit MFIs into dramatically increasing their microcredit loan interest rates. In many nations, these interest rates can trap microentrepreneurs — who are as objectively successful as Saima — in cycles of debt, leading MFIs to become de facto loan sharks in countries with particularly high interest rates. In addition, the neoliberal “solution” to the paradox of logics can actually further the inhibitory effects of patriarchy on microlending. Female borrowers are typically poorer than their male counterparts, so the vast majority of female clients do not fall into the profitable niche market that the new MFIs look to serve.

The new generation of MFIs has been characterized by resistance to female lending and unreasonably high interest rates. Simply put, international development agencies have created a lot more MFIs doing a lot less good.

However moving Saima’s experience with Kashif’s microcredit program may be, her story is an anomaly in the new era of microfinance. Geographical happenstance allowed Saima to experience the same level of service as the clientele of earlier microfinance groups, but the vast majority of nations do not posses Pakistan’s ability to surmount the paradox of logics. Thus, until the global development community comes together to address the ubiquity of microfinance’s for-profit trap, client success stories as impactful as Saima’s will quickly become rarities of a past era in micro banking.

References:

[1] Kristof, N. and WuDunn, S. (2009). Half the sky. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, pp.185-186.

[2] Microfinance Market Outlook 2014 (Rep.). (n.d.). doi:10.1787/weo-2014-7-en

[3] Wry, T., & Zhao, E. Y. (n.d.). Culture, Economics, and Cross-National Variation in the Founding and Social Outreach of Microfinance Organizations (Rep.). Retrieved September 2, 2015, from Global Initiatives Research & Teaching Materials Program at the Wharton School website: http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/conferences/2013-paulrlawrence/Documents/ZhaoWry_markets,%20culture,%20and%20microfinance.pdf

[4] Cull, R., Demirgüc-Kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2009). Microfinance meets markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(1), 167-192.

[5] Yunus, M. (2011, January 14). Sacrificing Microcredit for Megaprofits. Retrieved September 2, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/15/opinion/15yunus.html

[6] Center for Financial Inclusion blog,. ‘Smart Certification: Kashf Foundation Takes The Lead In Pakistan’. N.p., 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

[7] Hdr.undp.org,. ‘Table 4: Gender Inequality Index | Human Development Reports’. N.p., 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.