[slideshow_deploy id=’3739′]

I returned to Paris on the morning of November 16. I had been in Spain during the attacks, enjoying Armistice Day, a holiday in remembrance of those who died in WWI.

My bus got in at around 8 A.M., and I entered the Metro alongside multitudes of people on their way to work. I fell in with the masses, unwavering in their Monday morning routine. People spoke softly, looked for empty seats. I gazed into the absent eyes of those still half asleep, musing as I do about where they are inside their minds.

The train was delayed at Charles de Gaulle – Étoile and, deciding I didn’t want to wait, I changed to line 6.

The train’s departure was standard. But then, for a moment the lights flickered. The train halted, and the apprehension lying just below eyes glazed from sleeplessness became apparent on the faces of my fellow passengers.

I tried to imagine crossing the line between life and death in an instant, without preparation.

I thought of how I wouldn’t have cell phone service underground, to call a loved one.

If, that is, there was the luxury of foresight.

Then suddenly, we started moving again, just a train ahead of us running behind schedule.

The 6, to me, is the most beautiful line of the Paris Metro. It runs above ground and has one of the best views of the Eiffel Tower, a landmark that has yet to seem commonplace in my time living here.

This time, when we passed it, I suppressed the urge to cry.

We passed other sights that I could not look away from, like soldiers with machine guns. They have always been here, but not like this. I looked one of them in the eyes once and immediately had to look away, overwhelmed in imagining unnamable horrors–

I got off one stop earlier than normal after reflecting on how crowded my usual station is, how alluring it might be as a target.

I was late to class. I had forgotten all about the time.

My ID and bag were checked at the door.

While we detachedly discussed the policy of the EU in the Middle East during the class period, two other buildings at my school were evacuated due to a suspicious package. (It turned out to be the belongings of an absent-minded student).

Walking to a café to study after class, I came across a road blocked by police.

Walking home, I looked into the weary faces of people who had survived another day.

I made it back to my apartment. I had gone through the day’s motions, but my mind was somewhere else.

How do you pinpoint the feeling?

At first, overwhelmingly, it was one of disbelief.

How could this have happened?

Then of shock.

That could have been my friends… That could have been me.

Sadness, of course, followed. Heartbreak for those involved, affected.

And not long after, came fear. Not just for myself, but for what it all would mean.

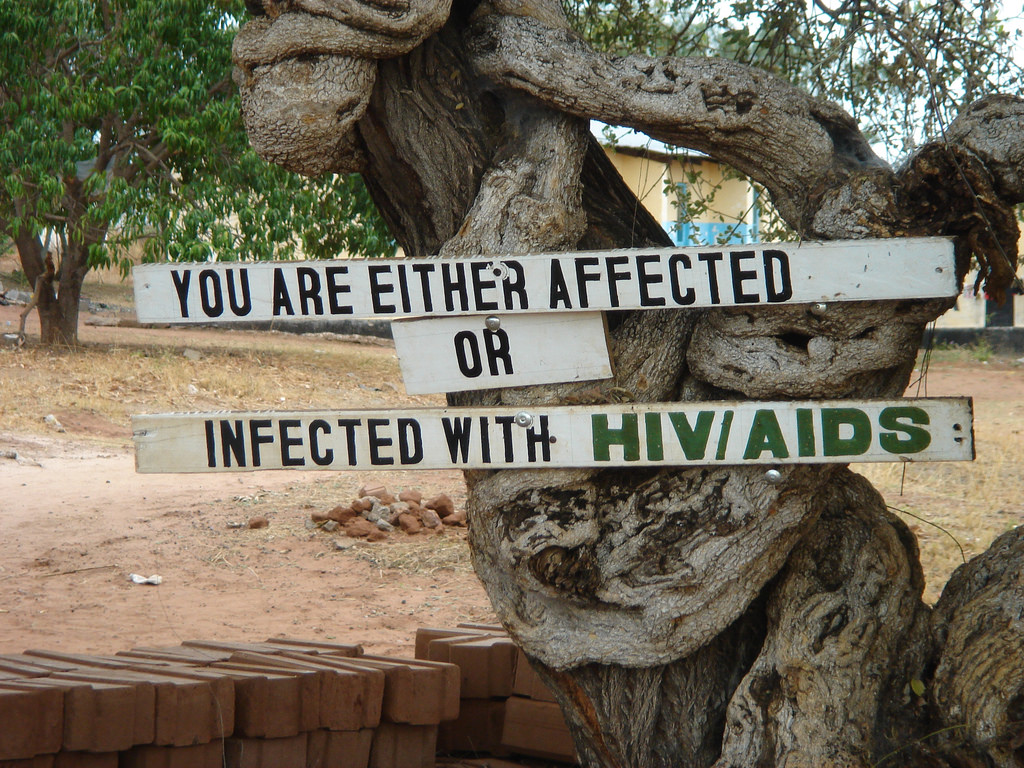

What will it mean for Muslims, already living under suspicion? For refugees, affiliated with extremism by the ignorant?

My pulse throbbed for them, the wrongfully accused. Refugee children, mothers, fathers, seeking sanctuary from unimaginable evil and faced with a wall of xenophobic hatred, all at once. Western citizens, living as outcasts under the banner of cultural and religious supremacy. Ordinary people, asking for nothing more than a home in the world.

And then I was transported back to the Boston bombings, to a realization they had led me to:

The privilege of entitled nonchalance.

Unbelievable were the tragedies in Boston, in Paris. Indeed, they did not fully register. A reality close enough to be felt, but to remain intangible.

While we donned shirts declaring “Boston Strong” and changed our Facebook profile pictures to overlay our faces with the French flag, we proceeded.

Life, for us, went on.

The tragedies, while difficult to swallow, eventually faded into the background because we had the privilege of leaving them behind. We were entitled to move on from these events because they were not pertinent to us. We could neglect them because we were Western, because we were white, because we lived in the ‘First World,’ because we were not Muslim.

Indeed, how, in our protected, privileged reality could we fathom the unspeakable horror that is to exist, no, to survive, under these circumstances on a daily basis? It is truly unimaginable.

Perhaps that is the reason why we turn from it and allow it to continue.

Thousands suffer while we play, complain about work, eat, simply live — the ultimate luxury that we have taken for granted.

We hide behind simulated acts of compassion, refer to a selection of emojis to communicate, in a neat little box, how we feel; swallow the realities constructed by the media.

We have lost our empathy.

We have reached a level of detachment, desensitization, perfected the act of apathy.

We have been unconscious for so long.

When, how, will we wake up?

I did not color my profile picture with the Facebook app. Not only because the site proudly forgot the tragedies in Lebanon, Kenya, Iraq, and other countless places touched by death, tacitly declaring those lost lives less worthy.

Trivial, even gross in its insignificance — literally applying a filter with the click of a button in response to the loss of hundreds of lives.

But then, as some ardently declare, does it really matter either way?

The emptiness of such actions, even well intentioned, is harmful, dangerous, because it creates the illusion of action. The false pretense of doing.

But the truth is, very few of us are effecting real change. We are not even so much as pausing to reflect and think critically.

We have reached the point where we are content to isolate ourselves within our comfortable lives, happily turned from the world’s ugliness, only until

the guns are at our own backs,

have taken the lives of people who look like us,

who “are” like us,

do we turn.

And even then, there is a fleeting sense of melancholy followed by the self-preserving thought:

“That means I could be next.”

What could possibly rouse us from this numbness?

What will convince us that more hatred is not the solution?

What will lead us to make a change?

What, finally, will this event mean for us?

It is a question of which I am frightened to receive the answer.

A question that has consistently been answered with the silence of inaction.

We have failed, time and again to produce the necessary response. We have failed to realize the importance of cultural inclusivity in schools, in policies, and in our personal lives. We have not translated the humanitarian musings so readily displayed on our social media accounts into confrontation of intolerance in reality. We have claimed to stand for liberty and equality for all, yet have watched without protest as those different from us have suffered continually under injustice. With each passing tragedy, we have not learned, and our actions do not say that we are sorry at all.

I imagine a world in which, tomorrow, business resumes as usual.

I hope with all my heart that the world proves me wrong.