Introduction to END7

END7 at NU is a budding student group at Northeastern that is in the process of becoming official. END7 at NU is a chapter of the larger nonprofit, END7, which is working to eliminate seven neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) by the year 2020. One in six people in the world are living with NTDs, which are different kinds of parasitic or bacterial diseases infecting their bodies. The effect is detrimental at best — deadly at worst — and perpetuates the poverty cycle in developing countries; children are prevented from attending schools and adults are prevented from working. The disabilities associated with NTDs are stigmatized within many rural communities and isolate those with poor health. Using mass drug administration techniques, the end of NTDs can be achieved. One packet of pills each year treats and protects children and adults from all seven NTDs. The medicine is donated by large pharmaceutical companies, and it costs only 50 cents per packet to distribute. Less than a dollar can protect a child from debilitating diseases for one year. END7 is working to increase awareness of NTDs in the developed world, raise funds to administer the drugs, and encourage the leaders of the world to take a stand against this injustice. If we all join in the fight, “Together we can see the end.”

If you want to help or get involved, visit: http://www.end7.org/support

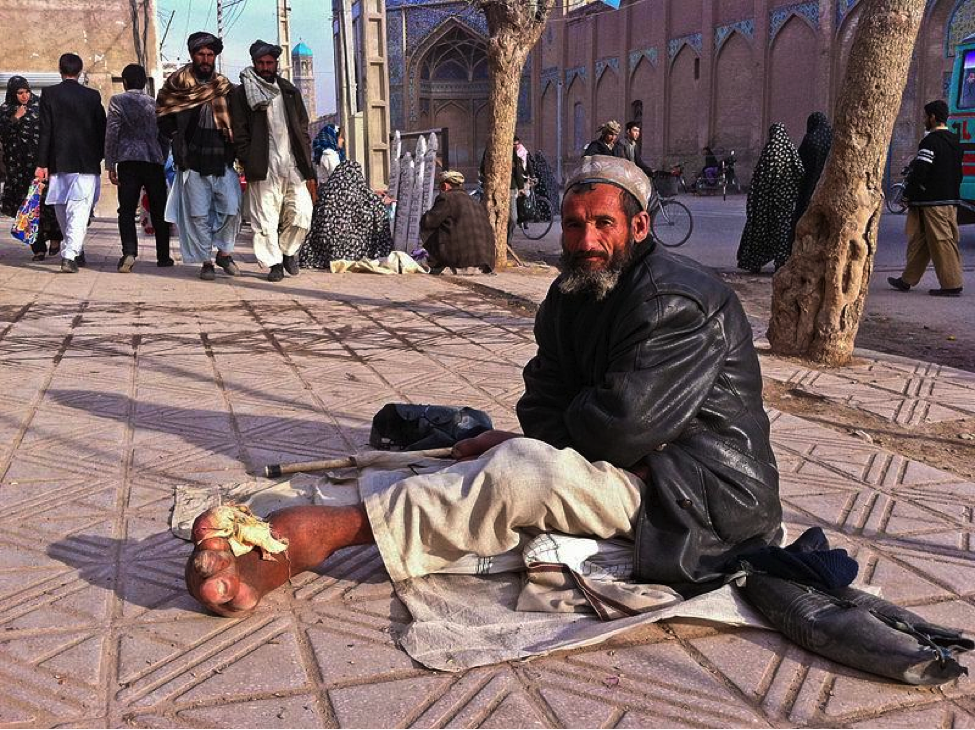

Elephantiasis is not the ailment that granted Joseph Merrick fame. The disease that incapacitates about 40 million people and has infected over 120 million is quite different, and less well known.[4] Also known as lymphatic filariasis, elephantiasis is caused by nematodes inhabiting the lymphatic vessels and nodes, transmitted as larvae from mosquito bites.[6] With the lymphatic system compromised by parasites, lymphedema, a painful swelling that affects the legs, arms, breasts, and genitalia, can occur. Between the incapacity of the lymphatic system and the increasing fluid accumulation, the body cannot fight infections as it once could. Bacteria becomes rampant and the skin becomes hard and thick until it resembles the skin of the disease’s namesake creature – the elephant. In some cases, those affected can have severe allergic reactions to the parasite as well. [6]

Eventually the legs become so swollen and painful they are no longer functional as limbs. Those affected can’t exercise or properly clean away the bacteria, leading to skin that is stiff and hard to the touch. The experience of what it would feel like if it also affected your genitalia is similarly painful. It would be near impossible to work or live a simple life, and that’s exactly what happens to millions of people. People cannot work so they cannot pay their medical expenses, and so the disease progresses without medical care, which then gets more expensive, and working gets harder and harder as the bills pile up. It’s a vicious circle. On top of this, physical deformities are not immune to social stigma and furthermore many cultures believe that it occurs as a result of voodoo, witchcraft, or evil. [3]

However, this disease can be treated. A drug called diethylcarbamazine can kill the worms with minimal side effects. Lymphedema can be managed with hygiene, exercise, and wound treatment. Hydrocele (swelling and fluid accumulation in the scrotum) can be treated with surgery. The goal is to get these treatments to those in need.[6] This means erecting a system that treats whole communities on a yearly basis. The drugs also reduce the rates of infection with intestinal worms. Despite elephantiasis being a neglected tropical disease, there is hope for eradication. Tens of millions of people are being treated every year through donations and China has even led a successful eradication campaign. Mohammed Laina, a man who has been successfully treated for his elephantiasis, puts it succinctly when he says “I have hope for the future.” [5]

Lena Bishop

Nursing ’16

References:

1. Ahorlu, C. K., Dunyo, S. K., Koram, K. A., Nkrumah, F. K., Aagaard-Hansen, J., & Simonsen, P. E. (1999, October 15). Lymphatic filariasis related perceptions and practices on the coast of Ghana: implications for prevention and control. Lymphatic filariasis related perceptions and practices on the coast of Ghana: implications for prevention and control. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001706X99000376?via=ihub#

2. Brown, D. (2012, October 2). Haiti takes on dreaded disease elephantiasis one mouth at a time. Washington Post. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/haiti-takes-on-dreaded-disease-elephantiasis-one-mouth-at-a-time/2012/09/30/53c5e5b0-afef-11e1-80eb-46875d0c7789_story.html

3. Elephantiasis And Witchcraft: 40-Yr-old Kills Grandmother | Social | Peacefmonline.com. (n.d.). RSS. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://news.peacefmonline.com/pages/social/201306/167701.php

4. Lymphatic filariasis. (n.d.). WHO. Retrieved March 21, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs102/en/

5. Tell us what you think of GOV.UK. (2012, January 27). Eliminating elephantiasis in Africa. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from https://www.gov.uk/government/case-studies/eliminating-elephantiasis-in-africa

6. Treatment. (2013, June 14). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/treatment.html