The Wolf of Wall Street, by Martin Scorsese, has just become the veteran director’s top grossing film after more than 40 years behind the camera.[1] The movie stunned audiences and critics alike, with its crude language and hedonistic plot. However, what makes the film so appalling to some members of society is what makes it so alluring to others. The playboy debauchery of main character Jordan Belfort seems too wild to be real, but the truth is that almost everything in the film comes straight from Belfort’s autobiographical book of the same title. Jordan Belfort is not a fictitious character birthed for the silver screen, but a real life boogie-man who plundered the coffers of wealthy investors from an ivory tower in the heart of New York City. From that tower, Belfort would descend to a prison in the American Southwest, along the way destroying his own life and changing the way Americans view the men and women of Wall Street.

The Wolf of Wall Street wastes no time jumping into the glamorous and perverse lifestyle of a crooked con-man working on Wall Street. The film begins with Belfort racing down the New Jersey Turnpike in a white Ferrari with a brand new wife and an undeserved sense of entitlement. From there things only amp up in intensity. Jordan spends the remainder of the film filling his body with booze, women, and quite literally every drug imaginable, only stopping briefly in a 1987 flashback, when a young and naive version of himself begins working at a legal stock firm in New York before being let go a short while later. Soon after being fired, Belfort comes up with the idea to start his illegal brokerage operation headquartered out of the fictitious (and WASP-y sounding) Stratton Oakmont stock firm. From his humble beginnings in 1987 to his arrest in 1998, Belfort went through two wives, multiple children, a Lamborghini and a multi-million dollar yacht that once belonged to Coco Chanel.[2] In the end, it was not the expensive lifestyle that destroyed Belfort’s life and company, but instead, investment fraud and money laundering.

Near the beginning of the movie, Belfort’s character, played by the charismatic Leonardo DiCaprio, looks at the camera and asks the audience a simple question: “Was all of this legal?” The short answer was no, no it was not. Before even starting his company, Stratton Oakmont, Belfort was breaking the law. After being laid off from his comfortable job on Wall Street, Belfort began working at a penny stocks firm on Long Island. There he would sell near worthless penny stocks, stocks in start-up companies that had almost no real value, to unsuspecting clients for a 50 percent commission on the value of the stocks sold. This was nearly 50 times the commission of normal stocks. The commission of these penny stocks is often referred to as “pink chips,” while commission on normal stocks is referred to as “blue.”[3] The selling of penny stocks in the US is not illegal, but since the value of these pink chips is often so little, it is a market that is heavily unregulated. Many firms are not even licensed with the US government, and often brokers working for these firms use fraudulent means to sell the near worthless stocks. Firms that deal in these sorts of penny trades are referred to as boiler rooms or “pump and dump” schemes.[4] According to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, brokers must fully disclose the actual value of a stock to an investor, provide a full and comprehensive document on the risks of investing in a particular stock, and disclose the commission that the company will make off of the investment.[5] None of these steps were met by Belfort or his coworkers. However, by avoiding the laws of the Exchange Act, Belfort was able to amass a small fortune and start up his own company.

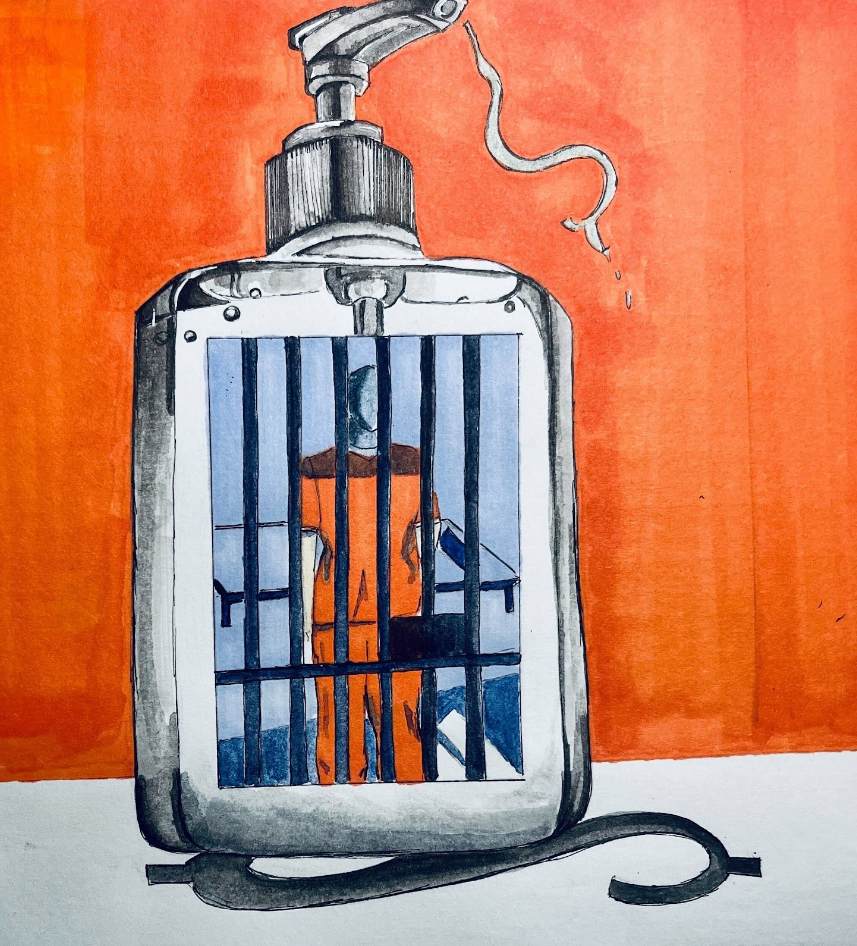

In the real world, Belfort was charged for an even more serious crime in addition to investment fraud: money laundering. The money laundering charges included smuggling more than $20 million into Switzerland in order to escape federal investigation.[6] Money laundering is the act of taking illegally obtained money and exchanging it for “clean” or earned money, via a business owned by a launderer.[7] Dirty money can also be invested into some form of capital, or in the case of Belfort, a Swiss bank. In short, Belfort could put $20 million unfiled dollars into his Swiss bank account and withdraw $20 million registered, seemingly earned, dollars within a short period of time. By committing the crime of money laundering, Belfort broke practically every law outlined in the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986.[8] In the end, Belfort only spent 22 months in a low-security prison in the Nevada desert.[9] His prison time would have been much harsher had he not chosen to cooperate with the US government and provide evidence against his former coworkers and friends in the business. Without cooperating with federal prosecutors, Belfort could have served 10 years for the fraud charges and more than 20 years for the money laundering charges. Judging by these harsh punishments, it seems that the system works. A man like Belfort, who had cheated his way to the top and stole hundreds of millions of dollars from hard working investors, could not escape the long arm of the law. However, the federal government took six years to finally tear down Stratton Oakmont, and much of the evidence against Belfort was obtained by coincidence in other investigations. True, there are laws in place to try and stop people like Belfort from abusing the capital system, but he was able to do it anyway.

In recent years, more people like Belmont have been exposed. Bernie Madof controlled a Ponzi scheme that stole more than $65 billion between 1990 and his arrest in 2011.[10] How are these people able to evade the authorities for decades and still make astronomical amounts of illegal money? Since the turn of the 20th century, little legislation has been written regarding stock market manipulation. The laws that have been passed such as the Exchange Act of 1986 and the Future Tradings Act of 1982 use vague language when outlining what practices are legal on Wall Street. For example, the Tradings Act of 1982 states that, “All boards of trade designated as contract markets ‘prevent the manipulation of prices and cornering of any commodity by the dealers or operators upon such board.’”[11] In essence, the responsibility to regulate and enforce against the manipulation of stocks was given to the heads of trading companies on Wall Street. This meant that those in charge of inspecting their companies of stock fraud were people like Belfort and Madoff; men who owned the companies they oversaw. Both of these Acts obviously have significant blind spots regarding enforcement of the laws that they outline. Both Acts also show the unwillingness of the US government to step in and enforce the rule of law by passing better, stricter legislation.

Money laundering, the second of Belfort’s crimes, is also covered in many US laws, most notably in the Money Laundering Act of 1986.[12] The Act itself is conclusive in defining what constitutes laundering and what the punishment for laundering is. However, since it was written in 1986, only 800 people have been convicted in major laundering cases.[13] That equates to a mere 32 convictions a year. Moreover, since the 80s, technology has made money laundering even simpler. The Belforts of the world no longer have to smuggle dirty money into Europe with mules, but can transfer funds electronically in seconds to unregistered accounts in Switzerland or the Cayman Islands. Since the beginning of the 2000s, new legislation has been created in order to combat large scale laundering rackets, but many of these new laws focus more on international money laundering for drug cartels and terrorist organizations.[14] This shows that the US government is more concerned with external threats rather than its internal problems. These actions are in response to global attacks such as September 11th and the July 7th London bombings, along with the inability of countries like as Mexico and Colombia to curtail illegal drug rings within their borders. Columbia alone accounts for over 43 percent of illicit coca growth in the world as of 2009, much of which travels north through Mexico and then eventually into the US.[15] The US government simply has too much on its plate to prioritize citizens within its own border smuggling their personal fortunes to and from American soil, because at the end of the day, cases involving people like Belfort and Madoff, who smuggle hundreds of millions of dollars at a time, are very rare.

In the end, who’s to stop men like Belfort and Madof? In recent years, the answer has been the people of the US. Just as it has for hundreds of years, the ability to curb injustice in our society has originated from the people. In the years that followed the 2008 recession, Americans took to the streets in protest of controversial Wall Street practices. The Occupy movement, as it came to be known, involved thousands of people, young and old, educated and uneducated, employed and unemployed, who stopped working and going to school to camp out in cities across America protesting not only unjust and illegal practices on Wall Street, but also the growing disparity between the rich and the poor.[16] In a live interview with NPR, Debra Dickerson, a retired US Air Force officer, explained why she joined the movement on the one-year anniversary of the first protest in New York City: “I have to be the world’s most unlikeliest rebel. I am 53 years old, and five years ago I would have been writing an op-ed for the Times that said I fail to see how sleeping in tents is going to help, but in the last five or so years I’ve had everything taken away from me – and I don’t even think it was personal, you know – by the one percent.”

The rally cry of these ragged men and women would become, “We are the 99 percent,” a personal distinction between the 1 percent of Americans who fall into the top income bracket and, well, everyone else. Now three years since the initial Occupy protest, many people question what the movement accomplished. No new legislation has been passed since the movement started in 2011, and many forget that it even occurred.[17] True, the movement was ineffective in changing the way the US government regulates Wall Street, and people like Belfort can continue to plunder the savings accounts of unwary Americans, but an important question was answered by the Occupy movement. The question was not, “Was this all legal?” (because it was quite obviously not) but, “Was this all acceptable?” Only the American people could decide that, and they replied with a howl of, “No!”

Emilo Cariati

International Affairs ’17

References:

[1] McClintock , Pamela. The Hollywood Reporter, “Box-Office Milestone: ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ Becomes Martin Scorsese’s Top-Grossing Film.” Last modified February 11, 2014. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wolf-wall-street-is-martin-679314.

[2] “Jordan Ross Belfort,” The Biography Channel website,http://www.biography.com/people/jordan-belfort-21329985 (accessed Mar 11, 2014).

[3 ]U.S Securities and Exchange Commission, “Penny Stocks Rules.” Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.sec.gov/answers/penny.htm.

[4]U.S Securities and Exchange Commission, “Penny Stocks Rules.” Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.sec.gov/answers/penny.htm.

[5]U.S Securities and Exchange Commission, “Penny Stocks Rules.” Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.sec.gov/answers/penny.htm.

[6] “Jordan Ross Belfort,” The Biography Channel website,http://www.biography.com/people/jordan-belfort-21329985 (accessed Mar 11, 2014).

[7] Daily Journal, “Money Laundering.” Accessed March 11, 2014. https://www.dailyjournal.com/cle.cfm?show=CLEDisplayArticle&qVersionID=123&eid=660921&evid=1.

[8]”Money Laundering Control Act of 1986.” Last modified October 27, 1986. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.ffiec.gov/bsa_aml_infobase/documents/regulations/ML_Control_1986.pdf.

[9] “Jordan Ross Belfort,” The Biography Channel website,http://www.biography.com/people/jordan-belfort-21329985 (accessed Mar 11, 2014).

[10] “Bernard Madoff,” The Biography Channel website,http://www.biography.com/people/bernard-madoff-466366 (accessed Mar 11,

[11]Fischel , Daniel, and David Ross. “Should the Law Prohibit ‘Manipulation’ in Financial Markets?.” Harvard Law Review. no. 1 (1991). http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1341697?uid=2&uid=4&sid=21103638424547 (accessed March 11, 2014).

[12] “Money Laundering Control Act of 1986.” Last modified October 27, 1986. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.ffiec.gov/bsa_aml_infobase/documents/regulations/ML_Control_1986.pdf.

[13] “Money Laundering Control Act of 1986.” Last modified October 27, 1986. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.ffiec.gov/bsa_aml_infobase/documents/regulations/ML_Control_1986.pdf.

[14] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “History of Anti-Money Laundering Laws.” Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.fincen.gov/news_room/aml_history.html.

[15 ]Badcar, Mamta. Business Insider, “11 Shocking Facts About Columbia’s 10 Billion Dollar Drug Industry.” Last modified April 22, 2011. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.businessinsider.com/colombias-drug-backed-economy-2011-4?op=1.

[16]Captain, Sean. Fast Company, “The Demographics of Occupy Wall Stree.” Last modified October 19, 2011. Accessed March 11, 2014. http://www.fastcompany.com/1789018/demographics-occupy-wall-street.

[17]Debra, Dickerson. “A Year On, What Did ‘Occupy” Accomplish.” September 17, 2012. March 11, 2014. http://www.npr.org/2012/09/17/161275527/a-year-on-what-did-occupy-accomplish.