Corruption is a contested concept with its understanding connected to societal, cultural and governance norms and values. A shorthand definition of corruption, found in the Transparency International Plain Language Guide, defines it as: “The abuse of entrusted power for private gain.”[i] According to the World Bank, for policy purposes corruption can be best understood as: “The abuse of public office for private gain.”[ii] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development notes that in criminal law no single definition exists but establishes “offences for a range of corrupt behaviour”.[iii]

Can corruption exist only in the public sector or does it also occur in the private sector? As most analysts agree that corruption exists in both, a more useful distinction can be made according to scale and context: “Corruption can be classified as grand, petty and political, depending on the amounts of money lost and the sector where it occurs”.[iv] Corruption can also be understood as systemic corruption or regime corruption – that is, the embedded corruption of an entire political and constitutive system.[v] Even the legality of corruption can become a question as, “TI [Transparency International] further differentiates between ‘according to rule’ corruption and ‘against the rule’ corruption. Facilitation payments, where a bribe is paid to receive preferential treatment for something that the bribe receiver is required to do by law, constitute the former. The latter, on the other hand, is a bribe paid to obtain services the bribe receiver is prohibited from providing.”[vi]

Can we differentiate between cause and effect? There are some who would argue that corruption is not caused by a specific type of system, but is rather a problem of certain corrupt individuals. Others agree that there are a multitude of causes of corruption, “Bureaucratic corruption seems to depend not on any one of the (three) factors identified, but rather on the balance between them. At one extreme, with few opportunities, good salaries, and effective policing, corruption will be minimal; at the other, with many opportunities, poor salaries, and weak policing, it will be considerable.”[vii]

Although the circumstances which encourage corruption are well known to include greed, erosion of values in society, scarcity of essential goods and services, poor and ineffective governance, inefficient judiciary, lack of transparency, cumbersome and complicated regulations, lack of competition etc, there are country-specific circumstances causing or facilitating corruption.

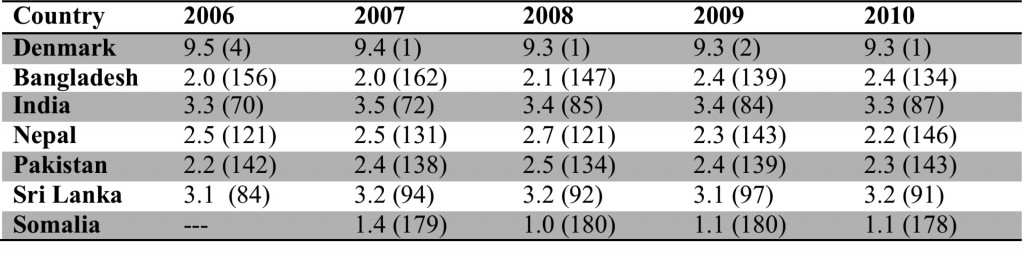

Regional variation is also apparent. In many regions corruption is a pervasive factor, with few exceptions. For example: “Corruption in the government procurement of goods, services and public works has been commonplace in Southeast Asian states (with the exception of Singapore) over many years. It has affected the provision of vital services and infrastructure and has been a key factor in undermining standards of governance.”[viii] Table 1 shows that among five states in South Asia over the last five years, corruption has remained constant at levels that place these states at the bottom of the list of countries included in the index.

Table 1

Corruption Perception Index in South Asia

Index (Rank)

This paper will discuss the links between corruption and national security and some of the successes and failures of various approaches to curb corruption, focusing on examples from Asia. In a broad overview of the effects of corruption on national security, security is applied very widely, including human security and the consequences of corruption for development. The approaches to combat corruption mentioned vary from efforts in government and business and from those involving the highest political levels to those involving everyday services.

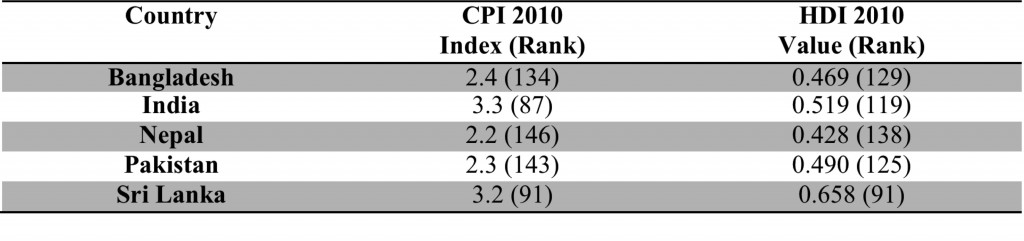

Corruption has had a profound and well-documented impact on security: “The cost of corruption is four-fold: political, economic, social, and environmental. On the political front, corruption constitutes a major obstacle to democracy and the rule of law…Economically, corruption leads to the depletion of national wealth…It undermines people’s trust in the political system, in its institutions and its leadership…Environmental degradation is yet another consequence of corrupt systems.”[x] On the human security front, the nexus between corruption and development is illustrated by Table 2, demonstrating that in South Asia, a region that falls well behind others in corruption, this correlates to lagging development indicators as well.

Table 2

Corruption and Development in South Asia

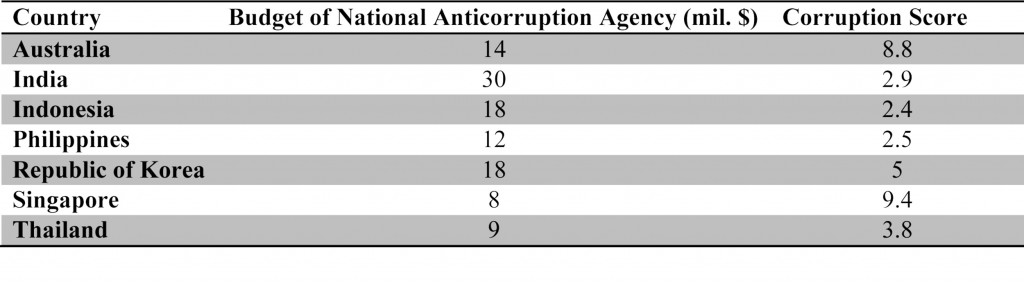

Despite some high-profile successes against corrupt public officials in China, “The latest blue book by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences showed that 86 percent of government administrations and 70 percent of city governments selected for analysis failed to pass its evaluation for transparency.”[xvii] Anticorruption agencies are often large and well-funded agencies with budgets that total many millions of dollars. However, corruption is not a problem that you can simply “throw money at” in hopes of a solution. While the answer may indeed be costly, Table 3 demonstrates that there is no correlation between the amount of money spent to manage corruption and real-world results. Furthermore, in societies riddled with corruption, especially in the public sector, government anticorruption agencies can be corrupted themselves. The bureaucrats charged with solving the problem may be swayed to other side and become a part of the problem themselves.

Burma has been listed as one of the most corrupt countries in the world for decades. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Index 2010, Burma is the second most corrupt nation after Somalia out of 178 countries. Nyan Tun Oo, a minister of the Rangoon regional administration, speaking at the first press conference to be held by the Rangoon administration since the USDP regime was sworn in on 30 March 2011 commented on the current regime’s plans to control corruption. He stated that the government could not take action against corruption as it would result in a shortage of experienced government staffers; “We cannot take action at the moment on corruption issues. If we did, who would replace all those corrupt officials?”[xviii]

How can we then interpret anti-corruption efforts if the corruption pervades even the highest ranks of government? Are these efforts used to simply reshuffle corrupt officials? Afghanistan’s Attorney-General has arrested high level officials on corruption charges, but they were then released on the orders of President Karzai. This first occurred in March 2011 when Noorullah Delawari, a ministerial-level presidential adviser on banking and the private sector, leader of the Afghanistan Investment Support Agency, and former governor of the Central Bank was taken into custody, then quickly released, with officials citing the entire incident as a misunderstanding. A similar incident occurred in 2010 when Mohammed Zia Salehi, head of administration for the president’s National Security Council was arrested on accusations of accepting a bribe, but released following a phone call from President Karzai.[xix]

One innovative solution to the scourge of corruption that would have benefits beyond improved governance is the greater inclusion of women in typically corrupt arenas. There is a popular concept that women are more honest men, but this may be supported empirically as, “…a number of studies argue that women are less tolerant of corruption than men, and that having more women in public life would reduce corruption. Statistics show that in the Asia-Pacific region, if a country has more women with secondary education, and a higher proportion of those working in the service sector are women, then the country’s score on the control of corruption index tends to be higher.”[xx] Cultural considerations are of particular consequence for this solution. For example, “In India and Bangladesh, women cannot normally participate in the male-dominated patronage networks through which corrupt exchanges occur, unless they are represented by male relatives.”[xxi] Although the exclusion of women from sectors of public life is a problem for these societies, in this instance it has had positive consequences for corruption control.

Threats to national security can be utilized to halt anti-corruption drives, as William Browder, a former businessman, will attest to: “For 10 years, I was the largest foreign portfolio investor in Russia, with 6,000 investors from 30 countries totalling $4.5 billion (£2.8 billion) under management. Our investment strategy in Russia was to improve rights of minority shareholders, promote good corporate governance and expose corruption. The trouble began after my fund launched a campaign to clean up the multi-billion dollar corporate malfeasance taking place in the Russian state-owned gas monopoly Gazprom, and in Surgutneftegaz. After we named names and exposed the details of several enormous corruption schemes, the Russian foreign ministry declared that I was a ‘threat to national security’. On November 13, 2005, I was deported and barred from re-entering the country.”[xxii] According to the adviser to the head of the Constitutional Court, Police Maj-Gen (retired) Vladimir Ovchinskiy, contemporary corruption revelations (for example, mass killing in the Krasnodar Territory village of Kushchevskaya in 2010 and the removal of office of the former Moscow mayor Yuriy Luzhkov or former head of the Moscow metro Dmitriy Gayev) should not be attributed to a struggle for power between Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, but rather simply cases of corruption too blatant to conceal.[xxiii]

The definition of corruption is contested regarding the sector where corruption can occur, the number of complicit actors, and the precise line between accepted and corrupt activities. However, all definitions involve a person misusing power or trust for their personal interests. Despite a paradox of possible economic benefits, corruption poses a proven threat to national security. The main consequences of corruption for security are political de-legitimacy, loss of state resources, leaking of sensitive technology, and incitement of public outrage. There have been a vast number of strategies proposed to tackle corruption, but their effectiveness varies dramatically from scenario to scenario, depending on the precise nature of the corruption and other specific cultural and societal factors. While grassroots efforts to fight corruption may have some success, to truly eradicate the problem it must begin where it is often the most deeply embedded, at the very top.

[i] “The Anti-Corruption Plain Language Guide”, Transparency International (July 2009): 14. The longer version reads: “Corruption involves behaviour on the part of officials in the public sector, whether politicians or civil servants, in which they improperly and unlawfully enrich themselves, or those close to them, by the misuse of the public power entrusted to them.” The Korean Independent Commission against Corruption supports this contention: “any public official involving an abuse of position or authority of violation of the law in connection with official duties for the purpose of seeking grants for himself or a third party” – “Corruption: A Glossary of International Standards in Criminal Law,” OECD (2008): 21-23. As does the Asian Development Bank – “Definitions of Corruption”, Asian Development Bank, Accessed 12 May 2011, http://www.adb.org/documents/policies/anticorruption/anticorrupt300.asp.

[ii] “Helping Countries Combat Corruption: The Role of the World Bank”, The World Bank Group (September 1997): 8-22.

[iii] “Corruption: A Glossary of International Standards in Criminal Law,” OECD (2008): 21-23.

[iv] “The Anti-Corruption Plain Language Guide”, Transparency International (July 2009): 14.

[v] Krishna K. Tummala, “Regime Corruption in India”, Asian Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1 (September 2006): 1-22.

[vi] “Frequently asked questions about corruption”, Transparency International, Accessed 12 May 2011, http://www.transparency.org/news_room/faq/corruption_faq.

[vii] Jon S.T. Quah, “Curbing Corruption in India: An Impossible Dream?” Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 16, No. 3 (December 2008): 240-259.

[viii] David S. Jones, “Curbing Corruption in Government Procurements in Southeast Asia: Challenges and Constraints”, Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 17, No. 2 (August 2009):145-172.

[ix] “Corruption and Bribery: National Security Impacts”, Campaign Against Arms Trade, Accessed 12 May 2011, http://www.controlbae.org.uk/background/national_security.php; “Corruption in the Philippines: Progress or payback?”, The Economist (5 May 2011); Freedom C. Onuoha, “Corruption and National Security: The Three-Gap Theory and the Nigerian Experience”, Nigerian Journal of Economic and Financial Crimes, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2009); R.S. Kamini, ‘Corruption a threat to national security’, New Straits Times (Malaysia), 9 December 2020, p. 19.

[xiii] “Tackling Corruption, Transforming Lives: Accelerating Human Development in Asia and the Pacific”, United Nations Development Programme (2008): 15-38.

[xiv] “Corruption and Bribery: National Security Impacts”, Campaign Against Arms Trade, Accessed 12 May 2011, http://www.controlbae.org.uk/background/national_security.php; “Corruption in the Philippines: Progress or payback?”, The Economist (5 May 2011); Freedom C. Onuoha, “Corruption and National Security: The Three-Gap Theory and the Nigerian Experience”, Nigerian Journal of Economic and Financial Crimes, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2009); R.S. Kamini, ‘Corruption a threat to national security’, New Straits Times (Malaysia), 9 December 2020, p. 19.

[xv] ‘Corruption as main threat to Russian security’, RIA Novosti news agency, Moscow, in Russian, 23 November 2010.

[xvi] Quah, Op. Cit.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Report by The Irrawaddy from the “News” section: “Sensitive News Barred: Rangoon Minister” Irrawaddy website, Chiang Mai, in English, 11 May 2011.

[xix] Rod Nordland and Sharifullah Sahak, ‘Afghan Aide Arrested, or Not, Officials Say’, The New York Times, 30 March 201, p. 12

[xx] “The Scourge of Corruption”, Op. Cit., pp. 20.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] William Browder, ‘We are not safe doing business in Russia; Employees are in constant danger of being harassed, arrested and killed’, The Daily Telegraph (London), 14 February 2011, p. 18.

[xxiii] ‘Russian Internet TV show discusses authorities’ inability to fight corruption’, RIA Novosti news agency, Moscow, in Russian, 24 February 2011.