On January 3, 2026, I woke up to the news that Nicolas Maduro—the man who led the regime that had terrorized millions of Venezuelans, including my own family, for opposing its corruption—had been captured and was awaiting trial. I do not know a single Venezuelan who has not personally suffered under Maduro’s leadership. Those who left were forced to abandon their homes; those who stayed live under an administration where speaking out could lead to arrest; and those who resist do so under constant threat of persecution.

Venezuela has lived through a painful cycle of hope for change, followed by constant disappointment. With Maduro’s arrest, the country now stands in a vulnerable moment where what happens next will shape its democratic and economic future. Unlike past moments of hope for free elections, this moment follows the removal of the regime’s head figure and offers the first real opportunity to restructure the corrupted institutions that made authoritarian rule possible. For the first time, regime leaders face real consequences under international threats.

It is understandable for everyday Americans and people around the world to be concerned—what is unquestionable is that Maduro is a dangerous criminal who should be arrested, and his loyalist regime should be as well. To some, Maduro’s arrest looks like the dangerous removal of a country’s leader. To Venezuelans, it looks like the first crack in a 27-year dictatorship that the world learned to tolerate.

Venezuelans around the world are celebrating Maduro’s arrest—and for good reason. For millions who were forced to leave their homes and families, watch loved ones be wrongfully arrested, and endure years of pain and suffering, Maduro’s capture feels like the first moment of justice in nearly three decades.

The modern fear, repression, and erosion of democratic institutions in Venezuela did not begin with Nicolas Maduro. Instead, they emerged with the rise of his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, whose consolidation of power dismantled the democratic and economic institutions of a once-prosperous country. Checks and balances became nonexistent, and the opposition was silenced and persecuted. The drastic changes soon transformed into a full-scale authoritarian and corrupt regime—one that would be inherited and intensified by Maduro. The outcome of this democratic collapse was the largest displacement crisis in Latin America’s history, with roughly 8 million Venezuelans forced to flee, not by choice, but by necessity.

So, how did Venezuela reach this point? It all started with oil and debt. Venezuela, with one of the largest oil reserves in the world, was once Latin America’s most prosperous nation. Since its discovery in the 1920s, the nation’s workforce has become excessively dependent on oil, which quickly became the backbone of Venezuela’s economy. Rather than precariously diversifying its economy, the nation continued to rely on oil revenue, leaving it vulnerable to price fluctuations and economic instability.

In 1976, President Carlos Andres Perez nationalized the oil industry as part of his ‘Gran Venezuela’ development plan. Then, in the early 1980s, global oil prices and demand dropped as Venezuela’s foreign debt rose. Perez had to make a decision, contradict his campaign and impose devastating changes to the economy, or continue sinking deeper into debt. It was a lose lose situation, rooting from decades of oil and wealth euphoria.

Perez’s solution was economic reforms referred to as ‘El Gran Viraje’, designed to address the crisis. The reforms were influenced by multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund. It included removing price controls, drastically cutting government spending and subsidies, devaluing the currency and dropping to its real market value—which made food and medicine imports far more expensive—opening the economy to foreign investment, and privatizing various nationalized industries.

Day-to-day life became more expensive, with gasoline prices rising 83% and public transport prices rising 30%, leading to immense social discontent. The final straw for the people was the bus fare increases. Prices increased but wages remained the same, so life became unsustainable. The response was explosive.

On February 27, 1989, thousands took to the streets in protest in what would later be known as the notorious ‘Caracazo’—a defining before and after in Venezuelan history. The majority of protesters were lower income citizens that were most affected by the reforms. Due to the police force being on strike at the time, also caused by the economic reforms, the situation escalated quickly. The government declared a state of emergency and then imposed martial law, instructing soldiers to restore order by force. Over 9 days, protests spread across the country, with the most violent being in its capital, Caracas. Official figures put the death toll at around 300, but human rights organizations estimate at least 1,000, with some placing the number closer to 3,000.

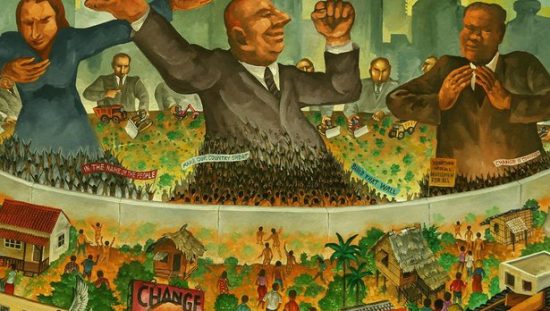

With the Caracazo, Venezuela’s image as a stable democracy collapsed and the hidden crisis of corruption and economic inequality came to light. The public trust in the government shattered, and demand for change intensified—setting the stage for the authoritarian dictatorship of Hugo Chavez, and eventually, Nicolas Maduro.

Acción Democratica and COPEI had dominated Venezuelan politics since 1958, after the fall of Marco Perez Jimenez’s 10 year military dictatorship. It created a two-party system that limited competition and political renewal. Over time, political accountability and the sense that parties tended to citizens’ needs reduced. Both parties became heavily dependent on oil revenue and traded on state resources and favors for loyalty. When oil prices fell and the economy raced towards crisis, poverty rose while the parties remained wealthy. The violence and unrest during the 1989 Caracazo deepened public anger and distrust toward the system. By the 1990s, Venezuelans largely viewed the AD and COPEI political parties as having failed to deliver solutions to the country’s growing crises.

Venezuelans didn’t turn to Chavez because they wanted a dictatorship. They turned to him because the old system had clearly failed them, and Chavez spoke to their anger and hunger for change, promising a system of equality and prosperity.

The Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200, a military organization led and founded by Chavez, soon gained widespread support. Before his political rise, Chavez was an army lieutenant colonel whose beliefs were fueled by opposition to the political elite.

On February 4, 1992, Chavez led an attempted coup d’etat against President Carlos Andres Perez. In other parts of Venezuela, the coup succeeded in briefly taking charge. However, they failed in Caracas, and Chavez surrendered. Though he was not supposed to speak on live broadcast, amid the chaos he was allowed to go live on air. He calmly and famously gave the speech in which he assured that the coup’s objectives had not been achieved “for now.” Chavez was then imprisoned, but he quickly gained support and became a figure of hope for change.

In 1993, Carlos Andres Perez was impeached for embezzlement and misuse of public funds, and the already weak trust and legitimacy of the two leading political parties since 1958 was further diminished. So, Rafael Caldera, a former president, independently ran for presidency with the promise of restoring stability and public trust in the system. However, the state of the economy and democracy of Venezuela was past the point of no return. Parties were weak, corruption remained, the economy was still damaged, and Venezuelans lost full trust in the system that once was.

In 1994, Caldera ordered Chavez’s release, and Chavez quickly gained even more support. Chavez employed a populist rhetoric that mobilized those most affected by the crisis by framing the system and the political elite as the enemy, deepening social polarization.

In 1998, Chavez was elected president of Venezuela. He promised to reconstruct the system, and he fulfilled this promise, dismantling the old two-party system and replacing it with a centralized model, with the initial approval of a large majority of the nation. Coincidentally, at the beginning of Chavez’s presidency, international oil prices rose due to an increase in global demand.

Initially, Chavez used the country’s oil revenue to fund social programs and to nationalize other key industries. The changes notably reduced poverty, particularly due to his spending pattern, expansion of the healthcare system, and the building of housing. He was adored nationwide by the people he was helping lift out of poverty, but his strategy was unsustainable.

Chavez repeated many of the same economic mistakes made decades earlier under Carlos Andres Perez. He relied heavily on oil for revenue and increased government spending while borrowing abroad, though on a much larger scale. Perez operated under the assumption that oil prices would not drop following the oil boom of the 1970s, while Chavez operated under the assumption that the much larger oil boom of the 2000s would continue at the same pace indefinitely.

When the economic crisis intensified and oil prices dropped, Perez turned to the economic package that shattered the public’s trust to save the country from certain financial ruin. By contrast, Chavez chose to double down on state control and spending—a continued mismanagement of the economy.

With their growing grip over the nation, Chavez’s government centralized power in the executive branch, therefore eliminating the one thing that makes a democracy function—the separation of powers. He weakened the private sector through the expropriation of companies, which contributed to rising corruption and total control.

Almost simultaneously, Chavez formalized Venezuela and Cuba’s partnership through various bilateral agreements. Venezuela agreed to sell 53,000 barrels of oil to Cuba daily. In return, Cuba provided thousands of medical services, doctors, and political advisors. Fidel Castro became a mentor to Chavez, and Cuban influence became foundational to Venezuela’s emerging restructured institutions.

In 1999, Chavez called for a new constitution which renamed the nation the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, approved the creation of a unicameral National Assembly, expanded presidential authority substantially, and centralized the power of institutions to his benefit.

It is important to note that this new constitution was eroding checks and balances and institutional democracy with extreme public support. One of the main lessons of the fall of democracy in Venezuela, is that democracies can erode while the anti-democratic leader still maintains public support.

Then, due to the mismanagement of nationalized industries, particularly the oil companies, and the expansion of government controls, there was a devastating economic and democratic decline that outlived Chavez. Following the lack of legal security in Venezuelan soil, foreign countries began to retreat from business with Chavez’s government, furthering the economic collapse.

In April of 2002, as political tensions rose, the first mass protests erupted in opposition to Chavez’s democratic backsliding. It marked the first regime-related deaths, after clashes between protestors and Chavez supporters driven by the deep political polarization. At least a dozen people were killed with many more injured. Days later, a coup briefly removed Chavez from power for 48 hours, before loyalists and mass protests restored him. This action permanently deepened Venezuela’s social division and further convinced Chavez’s supporters that the nation was in danger of foreign interests and corrupt elites.

Chavez remained in office for 14 years, during which he strengthened ties with Russia, Iran, and China, proposed the abolition of term limits, and reshaped Venezuela into an increasingly authoritarian regime. He remained in power until his death on March 5, 2013, where he succumbed to cancer. Before passing, he voiced his support for his Vice President Nicolas Maduro, were anything to happen to him. 30 days after his death, new elections took place where Maduro claimed victory, after which the situation only worsened.

Maduro continued Chavez’s pattern, accelerating the erosion of democratic institutions through the abuse of state power. The state intensified its suppression of the opposition and significantly limited freedom of speech through intensified censorship and systemic repression.

Violence and poverty spread, food and medicine became scarce, and economic collapse deepened. Maduro’s presidency saw further mismanagement and dependence on national oil, further concentration of power in the executive, hyperinflation, critical food and medicine shortages, and increased corruption in Venezuela.

Millions were forced to leave due to the severe shortages, making Venezuela unlivable for the vast majority of the population. As of 2024, about 8 million Venezuelans have fled the country in search of a better life elsewhere.

According to Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) World Report 2024, about 19 million people in Venezuela were unable to access adequate health care and nutrition. Earlier, HRW reported that between 2016 and 2019, police and security forces killed approximately 18,000 people in instances of “resistance to authority.” Foro Penal reports that since 2014, the same number of people were subjected to politically motivated arrests.

As conditions worsened, the country, formerly the wealthiest nation in South America, plunged into an extreme humanitarian crisis. Outraged by the country’s fast economic, social, and political decline, thousands of Venezuelans took to the streets demanding change. Under the State’s command, protests were constantly met with violence and repression. In 2017 alone, reportedly over 120 people died, and over 5,000 people were arbitrarily arrested, including 410 children.

In 2014, following the intensification of the crisis and the 2013 elections, mass protests also erupted across the nation. Human Rights Watch documented that Venezuelan security forces severely beat unarmed individuals, fired live ammunition, rubber bullets, and teargas canisters into crowds, and targeted journalists through arbitrary arrests. It also documented that officials severely beat and electrically shocked detainees, additionally often depriving them of food, water, and medical care. After that point, international organizations increased their watch over Maduro’s human rights violations.

There have been various peak periods of protests, all of which were primarily due to electoral results,where thousands were arrested, disappeared, or killed. The people of Venezuela wanted real political change, and fought for it constantly, but were met with devastating violence.

For most, the idea of freedom became unthinkable. Those who objected to Maduro’s regime were silenced through the spread of fear or by condemning them to political prisons such as El Helicoide, a detention center for political opposition where psychological and physical torture has been reported—widely regarded as the largest torture chamber in Latin America.

Electoral fraud regularly took place, with Maduro’s government rejecting the international claims of foul play. The 2014 elections were widely criticized for lack of transparency, and were accused of manipulation internationally in the 2018 and 2024 elections. His government and loyalists substantially controlled the electoral and judicial institutions, which ensured he remained in power and his supporters benefited. Meanwhile, the country was in an economic and humanitarian downward spiral.

Maduro placed the blame on external forces, such as sanctions, for the social, economic, and political crisis in Venezuela. In reality, sanctions and international legal measures before the late 2010s were mainly limited to targeted individuals linked to criminal or corrupt activity. The sanctions that could be said to have damaged the economy were not implemented until after 2017– much after the economy had already significantly deteriorated.

The electoral fraud was most relevant in the 2018 elections, after which many countries—such as the US and most of the European Union—rejected the electoral process due to irregularities—though North Korea, Cuba, China, Russia, and others still recognized him.

Then came the 2024 elections, when the future became unclear. The electoral process, and everything leading up to it, had many irregularities. Maria Corina Machado, a former member of the National Assembly, won the opposition primary to run against Maduro in the 2024 elections. But, much like many opposition politicians, she was restricted from running for office for 15 years by the National Electoral Council, which is run by Maduro’s regime, as a repressive strategy.

Maduro’s government had a notable track record of barring his opposers from running for office—this pattern was used as a tool to fill government positions with loyalists to further his hold over the nation. The workaround for this arbitrary decision to incapacitate Machado was to promote Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia, a former ambassador, to be her replacement. He was approved and became the opposition’s formal candidate.

On July 28, 2024, González, endorsed by Machado, historically swept the electoral polls—and, for the first time, there was concrete proof that Maduro’s victory was fraudulent.

It’s important to note that voting in Venezuela is done through a two-step process of public tally sheets and paper receipts, set by Chavez during the start of his presidency to protect against fraud claims. Maduro kept this voting system, but he eroded its actual transparency.

The opposition, led by Machado, painstakingly collected large portions of the paper receipts across every possible voting center in an attempt to formally prove the actual results. Maduro publicly claimed victory, despite never formally releasing the data. Not long after, the opposition released all available receipts, proving a significant victory for Gonzalez. Maduro did not honor the election’s results. Instead, he overrode them, choosing power and money over the will of millions of voters.

The people of Venezuela were outraged, and protests spread across the nation. Since then, there have reportedly been over 2,000 detentions for protesting, criticizing the government, and supporting the opposition, with many detainees being sent to El Helicoide. Over 800 political prisoners remain incarcerated now, and many families are yet to hear from their loved ones even over a year later.

International efforts, attempts at recall referendums, and revisions of the electoral process were attempted by various different institutions during Maduro’s time as president. The success of these were limited, however, because Maduro’s government significantly corrupted the integrity of state institutions.

On March 26, 2020, Nicolas Maduro and 14 current and former Venezuelan officials were indicted for criminal offenses related to drug trafficking and narcoterrorism. The US released a reward of up to $50 million for information that could lead to Maduro’s arrest, with many of his officials also having large reward offers. They were reported to be collaborating with various criminal organizations such as the Sinaloa cartel and Tren de Aragua. For the majority of Venezuelans, these charges do not even begin to represent a fraction of the pain, suffering, and collapse of the nation and its people.

After decades of failed attempts at restoring democracy, in a stunning turn of events, Nicolas Maduro and his wife were arrested through a United States military operation on January 3rd—something Venezuelans never thought would come to fruition.

Maduro and his wife are now in federal custody in New York, facing charges of narcoterrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, possession of machine guns and destructive devices, and conspiracy to possess machine guns and destructive devices.

The effects of his removal from power will cause dramatic shifts, the extent of which are yet to be determined. His vice president, Delcy Rodriguez, has since taken his place—an arrangement that continues to exclude the will of the Venezuelan people, underscoring how fragile and unfinished this moment of hope remains.

The United States’ removal of Nicolas Maduro was not random, and it was not a case of ‘removing a democratically elected president’ as some are concluding. The “democratically elected” president in this case has been eroding Venezuelan democracy for years, and is an international narcoterrorist.

This is not an endorsement for U.S. intervention or leadership. It is instead a reflection of the reality that Venezuelans are forced to live with after all democratic and legal paths to change were systematically destroyed.

Maduro and his government are brutal and anti-democratic, and they are responsible for torture, killings, and the destruction of the democratic and economic institutions of a once flawed, but prosperous country.

In the US, Maduro’s arrest has been met with mixed reactions, and its legality has become a controversial topic. While these concerns are legitimate, from the Venezuelan perspective, all possible ways to mobilize change have been attempted—protests, elections, international dialogue, and the presence of human rights observers—with no real result.

It is often argued that the United States became involved because of strategic and energy interests. Venezuela does, after all, sit atop one of the largest oil reserves in the world, and the United States has never hidden that reality. But under Maduro, none of that wealth benefited the people it was supposed to serve—not the schools that regularly close because teachers cannot survive on their wages, not the hospitals without medicine, and not the eight million Venezuelans who were forced to leave because they saw no future in their own country. Most Venezuelans do not think the United States’ actions were motivated by righteousness or respect for democracy. It is evident that the U.S. has its interests. But, for many, the idea that oil might finally be leveraged toward change feels like a path to potential freedom—risky, but to many, necessary.

This does not mean that Venezuelans wanted to depend on foreign intervention. It means that every path towards change had been tried and callously blocked by Maduro’s government. Maduro was not democratically elected, has been indicted for narcoterrorism, and his regime is corrupt and destructive—not just in Venezuela, but internationally.

We tried democracy. We tried law. We tried international pressure. We tried protests, and we were met with prison, torture, and death.

What comes next will determine whether Venezuela can finally move toward lasting change. For that to happen, the will of Venezuelans must at last be heard through free elections. But these will not matter without a prior redistribution of power. Venezuela’s institutions remain dominated by Maduro loyalists and collaborators, rendering any immediate vote fundamentally illegitimate and meaningless.

Under the continued pressure of international oversight and US involvement, a redistribution of institutional power is both possible and necessary. Only after this shift can elections be scheduled—elections monitored by international observers and conducted freely for the first time in decades. Venezuela cannot afford to lose yet another chance for real change. It is crucial for this chance to be different from the others.

It is easy to judge how people fight for freedom when you have never had to live without it, and just as easy to judge their reactions when things finally change. It just so happens that the United States’ interest in capturing a narcoterrorist aligns with the interest of Venezuelans to return to the rich, democratic country that it once was—and it is evidently not an accidental alignment of interests, as Venezuela remains home to one of the largest oil reserves in the world.

The best path forward is for Venezuelans to finally be in charge of their own destiny.

What will happen next is yet to be seen, and it is scary, but one thing is certain: with the arrest of Maduro, Venezuelans everywhere are now beginning to feel something new for the country many had begun to mourn: the possibility of hope, and with it, a chance to rebuild.