American policing was never a neutral institution; it was born from systems designed to control African Americans. Slave patrols, first organized in the 1700s, enforced curfews, hunted for enslaved people who ran away from their masters, and terrorized enslaved populations, embedding racial control into the very foundations of law enforcement. Even after slavery ended, these practices carried into Reconstruction-era policing, linking surveillance and punishment to Black life. Black Codes criminalized everyday behavior, convict leasing transformed false charges into forced labor, and Jim Crow laws restricted rights and movement, all ensuring that freedom for Black Americans remained conditional and tightly controlled. This history helps explain why “reentry” today is anything but a return. Though the word implies that someone is being welcomed back— back into society, back into the community, back into freedom—for millions of African Americans released from prison or jail each year, reentry is anything but a return. It marks the start of a new system of control.

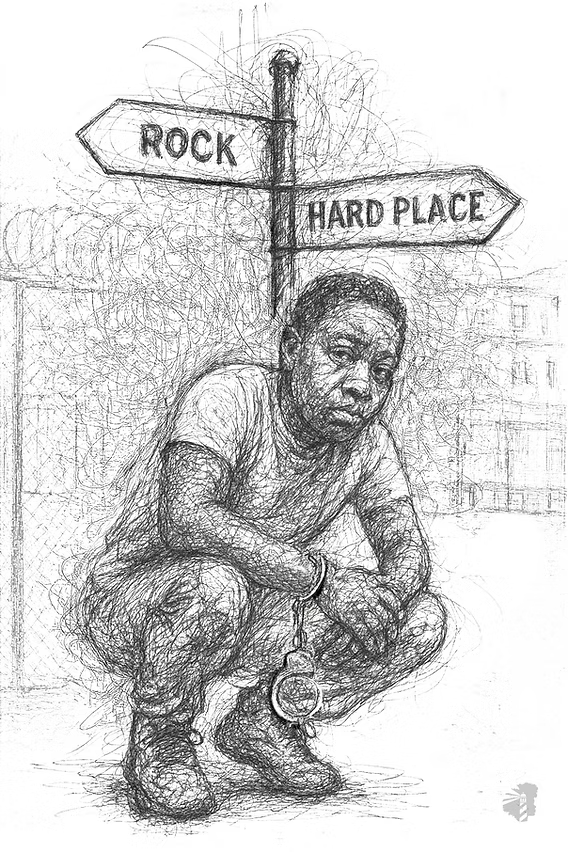

Reentry is a new set of systemic traps, barriers, and stigmas that continue to punish them long after they have served their sentence. These include losing access to stable housing, employment, and voting rights. Due to the fact that Black Americans are disproportionately incarcerated, these restrictions fall hardest on them, keeping cycles of poverty, exclusion, and surveillance in place. The United States incarcerates Black Americans at nearly five times the rate of White Americans, despite roughly equal rates of offending for most crimes. One in five Black men born today can expect to be incarcerated in their lifetime. Policymakers such as Presidents Bush, Obama, and Biden, along with members of Congress who sponsored the Second Chance Act, often frame reentry as a “new beginning” or “second chance.” They use this language to emphasize rehabilitation and promote opportunities for successful reintegration into society. But for the formerly incarcerated, the reality is that freedom is conditional, partial, and deeply restricted.

Even after release, systemic barriers in employment ensure that punishment continues, falling hardest on Black communities. Formerly incarcerated people face an unemployment rate of over 27%, nearly five times higher than the general population and higher than any recorded unemployment rate in U.S history, including during the Great Depression. For Black individuals, the rate is even higher. According to a 2003 study by Devah Pager, Black applicants without a criminal record were less likely to receive callbacks than white applicants with a criminal record. Repeated research on this topic demonstrates a consistent pattern of disproportionately denied employment compared to their other racial counterparts. This lack of stable employment is the direct result of legal and social systems that allow, even encourage, discrimination against people with criminal records. Families experience greater financial strain, children face instability that disrupts education, and entire communities are destabilized as concentrated unemployment fuels poverty.

Without stable income, many struggle to secure housing, support their families, or avoid returning to the underground community. The “underground community” refers to the informal or illicit economy (selling drugs, goods, services, weapons) that many formerly incarcerated people are pushed back into when barriers in employment and housing shut them out. Avoiding it is critical, as returning to this cycle often leads to instability and reincarceration.

Stable housing is also essential for reentry, but public housing is notoriously inaccessible to individuals with criminal histories. There are currently 1,3000 documented local and state barriers, plus 26 federal barriers, that restrict individuals with conviction histories from obtaining housing, and those incarcerated more than once face homelessness at rates 13 times higher than the general population. This disproportionately affects Black families, who are more likely to rely on public housing due to systemic economic exclusion. Even when only one family member has a record, the entire household can be penalized. Families may be denied public housing or even evicted under One Strike Policies, and benefits like SNAP or TANF can be reduced if one person is disqualified. As the NAACP Legal Defense Fund notes, this practice destabilizes communities and increases homelessness, especially among Black youth and formerly incarcerated Black women. The lack of stable housing and benefits also feeds back into the prison system itself, as Black people experiencing homelessness are more likely to be criminalized through ordinances against loitering, panhandling, or sleeping in public, making them vulnerable to arrest simply for trying to survive.

Access to education is similarly inequitable. 72% of colleges ask about criminal history on applications, and studies show that people with criminal histories are less likely to be admitted. Even when Black students are admitted, they may face additional scrutiny, from stereotypes about their qualifications to disproportionate disciplinary actions, while also having fewer financial aid options due to systemic wealth gaps and inequitable scholarship distribution.

These stereotypes are particularly harmful because they reinforce the false idea that Black people are arrested more often because they commit more crimes, when in reality, Black communities are disproportionately impacted by racial profiling and overpolicing in their neighborhoods. These barriers not only make higher education less accessible but also deepen long-term economic inequality. This is despite the clear evidence that education, especially post-secondary programs, significantly reduces recidivism by about 43% and improves quality of life. Equal access would not only expand economic opportunities for Black individuals but also strengthen family stability, reduce cycles of incarceration, and create lasting generational benefits.

Lack of access to public transportation is another often-overlooked barrier to reentry. Many predominantly Black communities are “transit deserts,” where reliable, affordable transportation is nearly nonexistent. While rural communities across the U.S. also face limited transit access, the issue takes on a distinct racial dimension in urban areas where Black residents are concentrated. Lack of reliable public transportation doesn’t just affect these communities; it affects poor people more broadly, who are disproportionately Black and Brown.

For wealthier suburban residents, limited train or bus service is often manageable because car ownership is assumed. But for low-income families without cars, the absence of accessible transit makes it nearly impossible to hold a steady job, attend school consistently, or even reach grocery stores. In this way, inadequate transit systems reinforce cycles of poverty and exclusion, deepening both racial and economic inequalities. Decades of redlining, highway construction through Black neighborhoods, and underinvestment in public transit have left Black communities cut off. This prevents individuals from attending job interviews, meeting with parole officers, or accessing healthcare. This in turn deepens poverty, increases the risk of reincarceration, and destabilizes families and communities.

Additionally, decades of urban planning decisions have isolated low-income Black neighborhoods from employment centers. These geographic inequalities intersect with criminal justice policies, contributing to parole violations and cyclical reincarceration. Policies that require frequent in-person meetings with parole officers, mandatory court appearances, and enrollment in treatment or job programs set people up to fail and often send them back to prison for technical violations rather than new crimes.

As if that is not enough, the surveillance continues. Parole, probation, ankle monitors, and mandatory drug testing all contribute to what many call “carceral citizenship,” a status that strips Black Americans of full rights while maintaining constant oversight. In this case, constant oversight refers to parole, probation, and heavy policing that keep Black Americans under strict supervision and threat of reincarceration, making their freedom conditional. Parole keeps people under strict check-ins, where even minor violations (missing an appointment, breaking curfew, or traveling without permission) can result in their return to prison. Probation imposes curfews and employment mandates. Ankle monitors extend prison into the home through constant electronic surveillance. Mandatory drug testing assumes guilt and penalizes individuals who miss or fail tests.

For Black Americans, reentry is not a guarantee of freedom; it is a continuation of a system that never let them go in the first place. From the beginning, Black Americans were trapped by slavery, Black Codes, and Jim Crow laws that criminalized their very existence and restricted their movement, labor, and rights. Today, that system persists through mass incarceration and reentry barriers that strip away their access to jobs, housing, voting, and public benefits, ensuring that punishment extends far beyond a prison sentence. In this way, reentry is not liberation but the new dominant mode of racialized social control in America. Without genuine reintegration, freedom is only an illusion. When returning citizens are denied fundamental rights and opportunities, they are set up to fail, and entire communities are forced to carry the weight of cycles of poverty, instability, and exclusion.

Changes must start with dismantling these policies. Voting rights, housing access, and employment opportunities must be fully restored the moment someone is released from prison. Investments in reentry programs that provide education, job training, and mental health support are essential to breaking generational cycles of incarceration. Ultimately, reentry must be redefined, not as a continuation of oppression, but as a genuine chance to rebuild lives and communities.