For centuries, people from Latin America have been coming to Chicago to escape persecution, poverty, and war. Mexican migration to Chicago began in the 1910s, spurred by the Mexican Revolution and the demand for labor during World War I. From 1942 to 1964, the Bracero Program brought Mexican laborers to the US to work primarily in agriculture, and some moved to urban areas like Chicago to work in factories. Similar economic opportunities brought Puerto Ricans, who are US citizens, to Chicago throughout the 1950s. Latin American migration to Chicago continued into the twenty-first century, with Mexicans remaining the largest group, followed by growing populations from countries like Guatemala and Colombia.

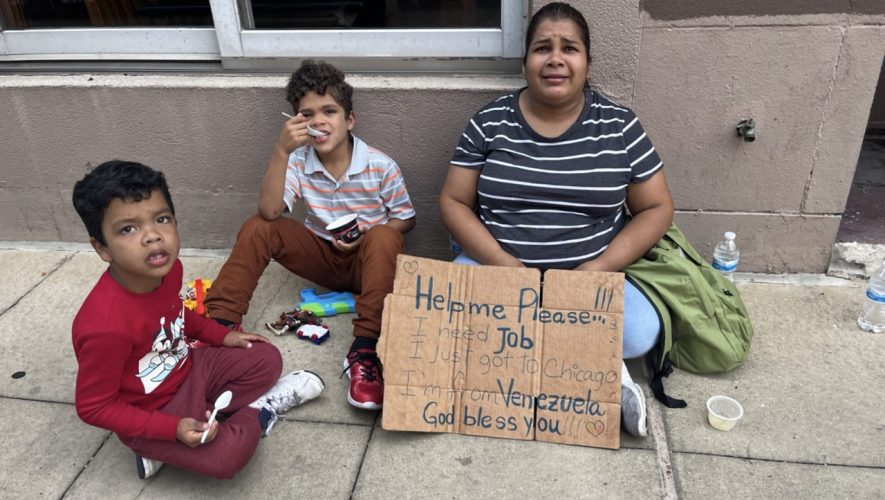

There are now waves of Venezuelan migrants flooding into Chicago, fleeing political turmoil only to reach an inefficient legal system. Without adequate financial support from the city to help immigrants join the workforce, the Venezuelan community will not be able to establish an economic and cultural hub in Chicago.

Historic Latin American Immigrants in Chicago

Today, the largest Latin American population in Chicago hails from Mexico, with one in five Chicagoans identifying as Mexican. Chicago’s Little Village, or “La Villita,” is often referred to as the “Mexico of the Midwest” because of its strong Mexican identity. Early immigration surges during the twentieth century allowed for future Latin-American immigrants to have a foothold with Mexican immigrant populations in the city, allowing the demographic to increase.

Aid societies, cultural centers, and places of worship have kept foreign languages and cultural traditions alive, creating vibrant ethnic enclaves and in turn benefiting the greater city. Marketplaces, artisan craft stores, and chilaquiles restaurants make La Villita a major economic hub for the Mexican-American community and one of the busiest commercial corridors in the city. The village features hundreds of Mexican-owned businesses, including bakeries, clothing stores, cafes, and grocers, enabling the community to generate billions of dollars in sales annually. Back of the Yards, located on the South-West side, shows how Mexican neighborhoods in Chicago are also often at the forefront of social justice movements, particularly around immigration reform, labor rights, and affordable housing. Back of the Yards has a strong sense of community, with residents working together to improve local services, schools, and public spaces, famously advocating for workers’ rights and improved living conditions.

Job disparity and legal status are the two biggest problems historically faced by Mexican Americans. Many Mexican immigrants in Chicago are undocumented, which limits their access to jobs, social services, and legal protections. These struggles have led to dangerous poverty trends for Mexican immigrants, making them vulnerable to exploitative employers who pay below minimum wage, deny benefits, or subject them to unsafe working conditions. Out of fear of deportation, some workers hesitate to report abuses or seek legal recourse. Mexican immigrants often live in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, where access to well-paying jobs, quality education, and healthcare is limited. As a result, they face higher rates of poverty compared to other demographic groups in Chicago.

Today, the largest Latin American population hails from Mexico, but recent political unrest in Venezuela is pushing Venezuelans to migrate to the US, and Chicago—being a sanctuary city—has been tasked to aid a portion of these immigrants. Although local and state government subsidized programs currently support Venezuelan immigrants in Chicago, such programs have spurred debates of ethical and economic sustainability. Chicago officials should recognize historic obstacles concerning Mexican immigrants in order to make way for a legal path to acquire job permits.

Busses to Chicago: The Recent Influx of Venezuelan Immigrants

Since August of 2022, Texas Governor Greg Abbott has bused over one hundred thousand Latin American immigrants from Texas border cities to Washington, D.C., New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Denver, and Los Angeles. An estimated fifty thousand immigrants have come to Chicago, with about thirty thousand coming from Venezuela. Non-profit organizations and volunteer groups rushed to support this massive wave of migrants alongside Chicago’s Mayor, at the time, Lori Lightfoot. Already facing high rates of homelessness, the city of Chicago created 28 housing shelters that offered Venezuelans, among other migrants, a temporary home to keep them off the street. These options proved to be ineffective, as degrading living conditions forced countless people out. Many Venezuelan migrants are now living in underpasses and public parks, or have moved to the suburbs. There are fewer than 5,400 people living in the city’s 17 remaining facilities as of mid-September.

Current migrant support programs demonstrate how Chicago has learned from its history, to a certain extent. Mexican immigrants weren’t provided robust municipal or state-sponsored immigrant aid to the extent that other immigrant groups were, particularly Europeans. The city lacked formal mechanisms to assist Mexican immigrants in accessing housing, jobs, education, and legal protections. Community organizations, churches, and the Mexican consulate provided far more valuable support.

Now, to support migrants in need of housing and provide them food, current Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson has designated a substantial amount of money for a migrant relief fund, while also tapping into COVID-19 relief funds. President Biden’s proposed bipartisan deal, which allocated $1 billion to local governments and nonprofit organizations around the country, could have helped resolve these issues. However, after former President Trump crushed the bill, the city of Chicago was forced to use $370 million of Chicagoans’ tax dollars to help feed, shelter, and care for migrants. This substantial amount of money allocated to the migrant relief fund, though an integral part of Mayor Johnson’s continued response, is not practical in the long run. Not only is this investment not sustainable for the city’s budget, but the use of this money has created divisions within the Chicago community.

When migrants arrive to any city, there is an immediate need for access to safe and humane temporary housing, food, health care, education, legal assistance, psychosocial support, etc., which former Mayor Lightfoot provided. Although these options show a step in the right direction, further income generating opportunities need to become available for migrants to succeed in a new country.

In Colombia, there are three million Venezuelan immigrants, two million of whom have received legal status in the form of a Temporary Protection Permit, granting them access to employment, a pension, and education. These working Venezuelans are living comfortably, have improved Colombia’s GDP, and have elevated the standard of living for Colombians.

In Chicago, only some Venezuelan immigrants have a path to obtain a work permit. If they arrived before July 31, 2023, they were afforded temporary protected status (TPS), which enables them to live and work in the US legally. Past July 31, most Venezuelans who have crossed the border are asylum-seekers protected by international law. This means they have one year to apply for asylum and can request a work permit 150 days after filing their application.

There is no guarantee these migrants will win their cases, or even have their cases heard. The process is consistently slow due to a significantly backlogged administrative system—an issue only exacerbated by the influx of thirty-four thousand immigrants who have arrived in Chicago since 2023. The system for acquiring a legal permit to work and therefore gain a steady income is lengthy or non-existent.

A Possible Solution

For Venezuelan immigrants to settle comfortably in the city of Chicago, as Mexican immigrant communities did in the twentieth century, the city must offer a clear path towards financial stability. Chicago’s booming industries in the early twentieth century, particularly in steel, railroads, and meatpacking, actively recruited Mexican workers to fill labor shortages which allowed for Mexican immigrants to find economic success. A stable income is fundamental for securing housing, food, healthcare, and education—all of which are essential for personal stability.

The job market in Chicago is high, projected to grow, and can be filled by Venezuelans, but the current legal process for receiving a right to work permit is ineffective. Mayor Johnson should divert funds from the migrant crisis fund to focus on acquiring work authorization workers, something the Biden Administration failed to deliver. The city plans to spend $150 million on the migrant crisis in 2025 to cover the cost of housing, food, and care for those who have recently crossed the southern border. The city’s plan translates to spending more than $2,000 per month per person, which is far greater than what is federally allocated for low-income Americans. A more economically sustainable plan in the short term will yield long term benefits, saving money for Chicago while also supporting Venezuelan immigrants.

With the correct investments towards expediting the legal status process for migrants, allowing them to join the workforce, Venezuelan migrants can firmly settle in Chicago soil and build an economic and cultural hub of their own.