Illustration by Alex Nabaum

Last December, the United States began vaccinations for COVID-19. While lawmakers, frontline health officials, and at-risk Americans are already receiving theirs, it is likely that the public will not be sufficiently vaccinated until summer, as the Trump administration left states virtually no plan for distribution. However, its rollout is incredibly promising, and has major implications for finally stopping the virus that has taken 2.5 million lives worldwide.

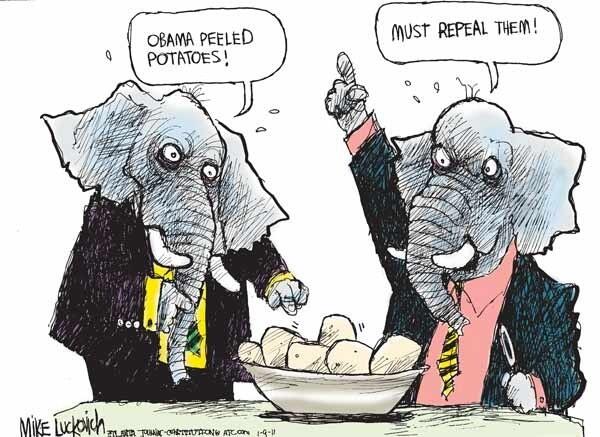

But we are not out of the woods yet. The US must contend with its own unique conundrum: how to deal with the sizable percentage of the population that is skeptical about taking the vaccine. After an entire year of President Trump politicizing public health and science, a great deal of damage has been done to the cause of our nation’s recovery. According to a Gallup poll in January, half of Republicans said they would not take a COVID-19 vaccine, a number that hasn’t changed much since September.

However, many in the media have focused their scorn on another skeptical group: African Americans. According to a November poll, only 53 percent of non-White Americans plan to take the vaccine; this number has spiked to 72 percent in the past few months. The Black community’s decades-long distrust of the medical profession persists despite the pandemic’s outsized effect on them. Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to contract and die from COVID-19 and, along with Latin Americans, comprise 80 percent of those facing eviction. They are also being unequally vaccinated despite their higher risk. Despite these harsh realities, many simply cannot fathom Black communities’ concerns, and have resorted to dismissive scolding and lecturing.

This attitude was evidenced in a viral story spread in right-wing outrage circles purporting that Cornell University was exempting Black students from vaccination requirements because of historical racism. While the story was debunked—Cornell acknowledged that medical racism might cause some discomfort with vaccinations, but made clear this was not grounds for an exemption—its prominence showed how ready the country is to gaslight the Black community into questioning its reticence.

All Americans need to get the vaccine. African Americans are no different. In fact, without Black acceptance of the vaccine, we will not reach herd immunity, which is necessary for returning to some semblance of normalcy. But we cannot talk down to marginalized communities about their suspicions. People of color have legitimate concerns that stem from decades of medical racism and being treated like their lives do not matter. They don’t fear vaccines because of some nonsense conspiracy about Bill Gates and George Soros implanting them with microchips; they are simply apprehensive of a profession that has caused them endless suffering packaged under the veneer of “trust me, I’m a doctor.”

The specter of scientific and medical racism permeates all interactions between doctors and the Black community. Since slavery, the bodies of Black people have been seen as expendable and exploitable. James Marion Sims, the “father of modern gynecology,” came to his discoveries on vesicovaginal fistulas (VVF) through the violation of slave women, for the ends of repairing a condition that hindered their ability to do hard labor. His experiments were a heinous perversion of the all-important doctor–patient relationship. To call these women patients is itself inaccurate, for the women gave no consent. The only people Sims considered were the women’s masters, whose consent he had to obtain, lest he deprive them of their property. Sims perfected his procedure for repairing VVF through tortuous experiments without anesthesia.

Later, when studying neonatal tetanus, Sims hypothesized that the condition stemmed from movement of the neonatal skull during protracted birth. His method of testing this? Prying the skull bones of infants into alignment with an awl, killing them.

Sims was not an anomaly. The practice of conducting studies on slaves was quite common, with prestigious medical schools taking part. The widespread availability of “specimens” was promoted by Southern schools to attract students. Writing about the tragedy, historian Deirdre Cooper Owens remarked on the irony of the enslaved’s cruel existence: “flesh-and-blood contradictions, vital to their research yet dispensable once their bodies and labour were no longer required.”

Even in death, the Black body could not escape the desecration of the surgeon’s knife. Medical schools widely employed “resurrectionists,” or grave robbers who would steal Black corpses from their graves for experiments, sometimes enlisting slaves to sneak into segregated cemeteries. The odious stain of this crime touches many universities, such as the Virginia Medical College and the Medical College of Georgia.

Black and brown people have also consistently found themselves victimized by eugenics, the attempt to create a “genetically superior” population by allowing only “pure” or “desirable” groups to reproduce. A growing movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, eugenics became widely accepted among Social Darwinists, White supremacists, and even progressives in America, while also driving the European fascist movement. It wasn’t a fringe idea; its central tenants took hold not only among “erudite” academics and the wider public, but were also codified into law.

Eugenics were the basis for the acceptance of forced sterilizations, which the Supreme Court endorsed in 1927’s Buck v. Bell. The case concerned Carrie Buck, an institutionalized young White woman who had been sterilized by the state of Virginia. Buck herself was given little consideration during trial; her lawyer made no real effort to advocate for her since he had ties to the institution that had sterilized her.

In writing for an 8–1 majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. found the statute constitutional and in the best interest of all parties, citing the circuit court’s claim that Buck was “the probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring.” Both courts relied on junk science and did not question the notion that the institutional facilities could determine whether someone’s “imbecility” was hereditary, much less whether the state had the right to violate their body to stop their procreation. The court took Buck’s poverty, alleged delinquency, and “promiscuity” (having a child out of wedlock after being raped) and spun a narrative of incurable, hereditary stupidity.

“It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

–Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Buck v. Bell (1927)

This horrendous decision gave states the legal basis to enact sweeping sterilization laws. Over thirty states did so, leading to the sterilization of an estimated sixty thousand people. While many poor and disabled White Americans were also victimized by sterilization, the rationale behind it—that only some are fit for civilization—was inherently racist. California’s laws helped inspire Nazi Germany’s, and five thousand of the eight thousand sterilized in North Carolina were Black. North Carolina did not abandon its program until 1974. The Supreme Court never overturned Buck v. Bell, and the Eight Circuit Court of Appeals cited it in 2001.

Furthermore, sterilizations and the perverse eugenics behind them persist to this day. Sterilizations are used heavily in plea negotiations and sentencing, perpetuating the racist, mythical link between genetic deficiency and criminality. The practices skate by because they are voluntary on paper. In 2009, a woman was forced to undergo sterilization as part of her plea agreement to stay out of jail for marijuana distribution. A Tennessee judge in 2017 offered a thirty-day sentence reduction for prisoners taking “long term birth control.” These coercive practices are allowed to continue for the same reason as the previous atrocities; those in the criminal justice system—overwhelmingly poor, Black, and brown people—are not seen as human.

State medical violence has not been limited to the Black community. Between 1973 and 1976, the United States Indian Health Service sterilized over 3,400 Native Americans without their consent, and attempted to cover up the extent of the crime for years. The native community, whose mistreatment predates slavery, harbors a similar distrust of the COVID-19 vaccine. When Pfizer came to the Navajo Nation for volunteers for their clinical trials, they were met with legitimate fear from a community that has been ravaged by the disease.

“The first thing I thought was just ‘No,’ you know, ‘why is this happening?’” commented Roxanne Tsosie, a Navajo woman in New Mexico who has lost four family members to the virus. Tsosie, clearly not a COVID denier, has reasonable reservations about being treated like a guinea pig: “Hearing about it just runs through the whole quick history in your head. It just kind of makes me sick.”

These are not irrational actors deserving of condescension. They are real people whose concerns need to be addressed directly.

The former incidents cast a massive shadow over the medical profession. Yet no one event has shattered the trust of communities of color as much as the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” In 1932, the Public Health Service (PHS) sought out the assistance of the Tuskegee Institute, the university founded by former-slave-turned-intellectual Booker T. Washington, and a source of pride in the Black community. The PHS was looking for volunteers for a study on the effects of untreated syphilis, and found easy prey in destitute, illiterate sharecroppers who had no hope of medical care otherwise. Enticed through free rides, check-ups, and meals, six hundred men enrolled—399 with syphilis and 201 without as a control group. The men were told nothing about their condition or the true nature of the study, only that they were being observed for their “bad blood.”

The men were told the study would last six months. Instead, it lasted forty years, in which time penicillin was discovered to be an effective treatment for the disease. Yet not a single one of the men were given this as treatment, as doctors disguised placebos and fake medicine to fool their subjects. To study its effects, researchers let the disease rage unabated in the withering bodies of their patients. The study was only ended when the Associated Press exposed it in 1972, little consolation to the hundreds of families it destroyed. The study’s authors had no qualms about altering their experiment for unethical ends; they offered less consideration to their patients than they would to a test rat.

The repercussions of the experiment cannot be understated. Researchers in 2017 noted that the disclosure of the study correlated with a massive decline in interactions between Black men and doctors, as well as an increase in medical mistrust and mortality. The effects were so great that the authors estimate that the life expectancy of Black men at age forty-five dropped by almost 1.5 years in response to the disclosure. It also accounted for 35 percent of the 1980 life expectancy gap between Black and White men, as well as 25 percent of the gap between Black and White women.

Even before the 1972 revelations, the inhumanity with which Black patients were treated was well known. An infamous scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man displays how Black patients were subjected to callous, sadistic doctors willing to use their bodies to test illegal procedures they would have never dreamed of attempting on White Americans. The narrator, waking in a hospital after being injured in a paint factory explosion, finds himself at the mercy of two surgeons eager to “cure” him with shock therapy.

“Nonsense, from now on do your praying to my little machine. I’ll deliver the cure.”

“I don’t know, but I believe it a mistake to assume that solutions—cures, that is—that apply in, uh . . . primitive instances, are, uh . . . equally effective when more advanced conditions are in question. Suppose it were a New Englander with a Harvard background?”

“Now you’re arguing politics,” the first voice said banteringly . . .

“But what of his psychology?”

“Absolutely of no importance!” the voice said. “The patient will live as he has to live, and with absolute integrity. Who could ask more? He’ll experience no major conflict of motives, and what is even better, society will suffer no traumata on his account.”

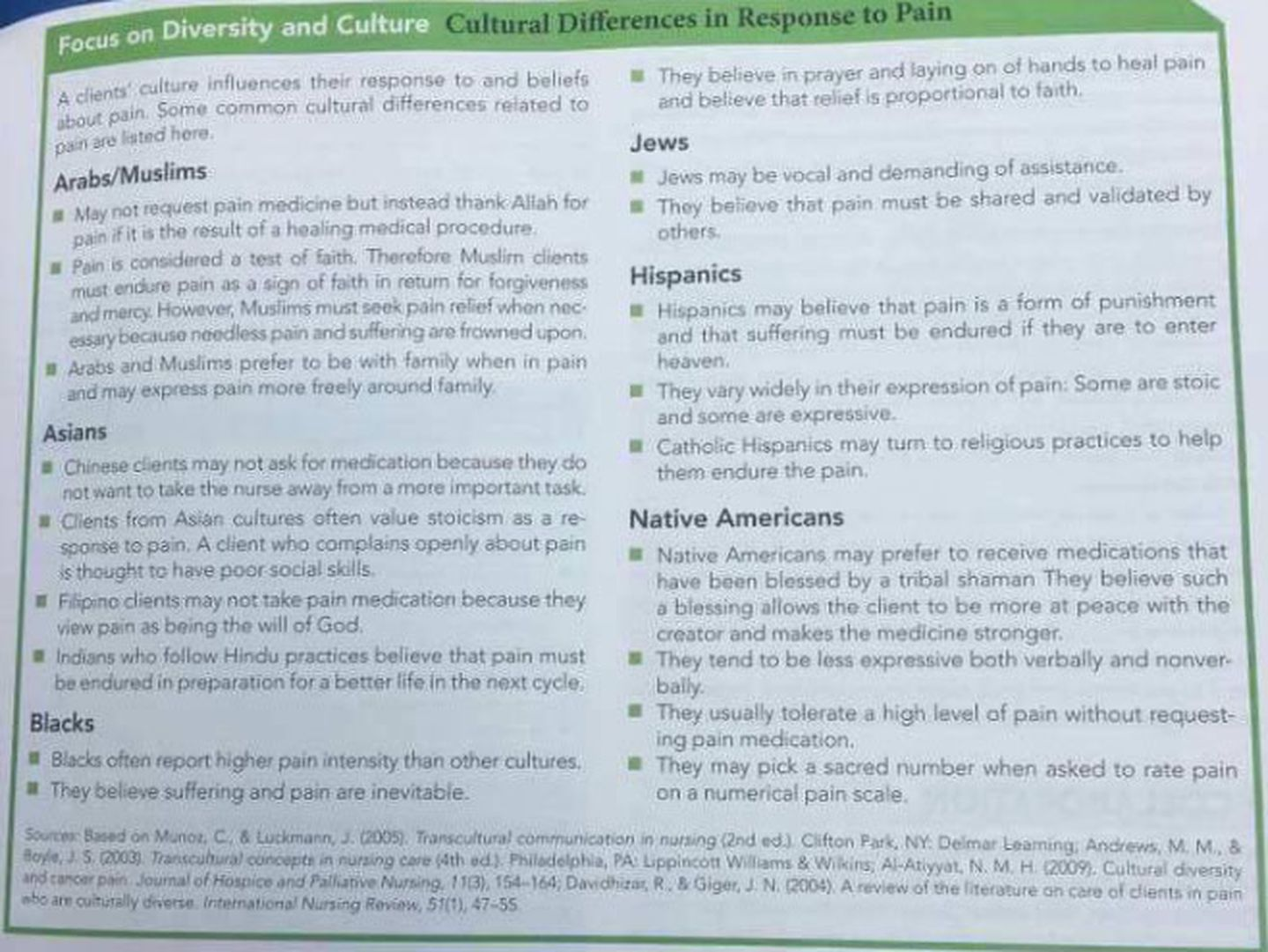

Even when they are not being directly exploited, Black Americans have learned to expect lesser treatment and dehumanization from healthcare professionals. The medical field is saturated with harmful stereotypes about Black people, like the belief that they have a higher pain tolerance. A 2016 study showed that half of medical trainees held false beliefs about Black patients, assuming they had less sensitive nerve endings, thicker skin, or blood more prone to coagulation.

Black Americans are not taken seriously when they profess to feel pain; they are consistently prescribed pain medication at rates much lower than White Americans. Doctors who held false beliefs about Black anatomy were also shown to be more likely to give Black people inaccurate treatment recommendations. The problem is so pervasive that some Black people have learned they must exaggerate their pain in order to convince doctors.

These antiquated ideas have been reinforced by older members of the medical community and textbooks that students use. Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning traffics these stereotypes openly, stating that Black people and other ethnic groups are more acclimated to pain, and that it is part of their culture. An old textbook, a relic of another time? No, it was published in 2015, and was widely circulated until the following page went viral in 2017.

Any and all conversations about the COVID-19 vaccine should be centered around evidence and a sensible discussion of the science of vaccines. Informed discourse will always be more effective than moral scoldings. All people want is what’s best for their health and that of their loved ones; it’s merely a matter of making a solid case that the vaccine is a means to this end. Explain the science, and do not resort to trite dismissals of concerns with “just trust the scientists.”

While not everyone is a doctor, most people are smart enough to understand the basics of why vaccines are necessary, and appreciate not being talked down to. Yet conversations also shouldn’t devolve into a confusing mess of medical jargon and technobabble. Esoteric language that makes people feel like they’re being misled is just as damaging as condescension. These tactics are race neutral, and should be applied to anyone who is concerned about the vaccine (provided that concern is not rooted in outright conspiracy).

The relevance of race lies in awareness of a certain group’s apprehensions, not in presenting a specialized way people of color should be spoken to about the vaccine. An attitude of enlightened White saviorism is detrimental to the goal of spreading vaccine awareness, and will perpetuate long-standing racism.

Everyone needs to take the coronavirus vaccine. Marginalized communities of color are no exception. Yet their concerns should not be brushed off as nonsensical conspiracy as those of COVID-19 deniers can. The long history of medical racism and structural violence toward these communities must be understood if we are to get everyone on board.