Content Warning: This article discusses sexual assault and violence.

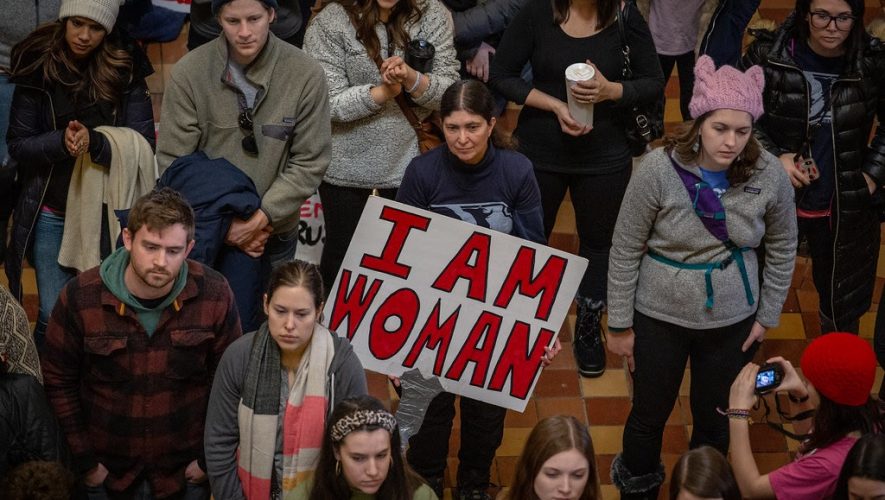

University life should be exhilarating, a time for exploration and enjoyment. But about 11 percent of all students are sexually assaulted during their time in college. For gender-nonconforming and undergraduate female students, the rate is almost 25 percent. This is the problem Title IX is tasked with resolving.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

– Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972

Before Title IX, colleges prohibited female attendance, set admissions quotas, and required women to receive higher grades and test scores than men for admission. If accepted, women were excluded from “male” programs like medicine, faced restrictions such as earlier curfews than males, and had limited access to scholarships.

Two key Supreme Court decisions—Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District in 1998 and Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education in 1999—set the precedent on this mandate. The justices concluded that educational institutions were accountable for sexual harassment only if they had “actual knowledge” of the misconduct and responded with “deliberate indifference.” The harassment also had to be “so severe, persistent, and objectively offensive that it effectively barred the victim’s access to educational opportunity.” The court excluded “minor” sexual harassment that still helped to create a hostile environment for all women, especially survivors.

There was minimal change to the Title IX policy under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. President Barack Obama extended Title IX protections to consider sexual assault as a civil rights matter.

In 2011, the Department of Education’s (DoE) Office of Civil Rights released a nineteen-page document known as the “Dear Colleague” letter. It contained a new federal regulation that required campuses be devoid of sexual harassment and assault. The DoE argued that sexual violence bars equal access to education; therefore, universities must “take immediate action to eliminate the harassment, prevent its recurrence, and address its effects.” Schools that failed to do so could lose federal funding.

The DoE released a more detailed policy in 2014, establishing a controversial standard for proof—“preponderance of the evidence,” also known as “50% plus a feather”—in disciplinary hearings. This standard was more lenient than its alternative, which demanded that a plaintiff prove that their accusation was very likely true. Obama’s policy dissuaded cross-examination and live hearings. The White House and DoE also pressured schools to appoint one person to investigate and decide whether there was misconduct.

Many congressional Democrats and survivor groups applauded the policies for focusing on survivors, as complainants were less likely to face the accused face-to-face. However, some law professors, the American Bar Association, and a former president of the American Civil Liberties Union asserted that the lack of in-person cross-examination would impede fair adjudication.

In 2016, the Republican Party’s platform echoed those criticisms, saying that the Obama administration’s “distortion of Title IX to micromanage the way colleges and universities deal with allegations of abuse contravenes our country’s legal traditions and must be halted.” The Trump administration’s Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, withdrew the administration’s guidance in 2017.

However, it took over three years for the DoE to release new rules on sexual misconduct. Their policy—which went into effect in August—is a middle ground between Obama-era policies and the prior Supreme Court precedent. Some have praised the policy’s reinstatement of live hearings and cross-examination, while National Women’s Law Center leader Catherine Lhamon, former DoE Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Fatima Goss Graves, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi argued that these measures burden victims and let abusers off the hook.

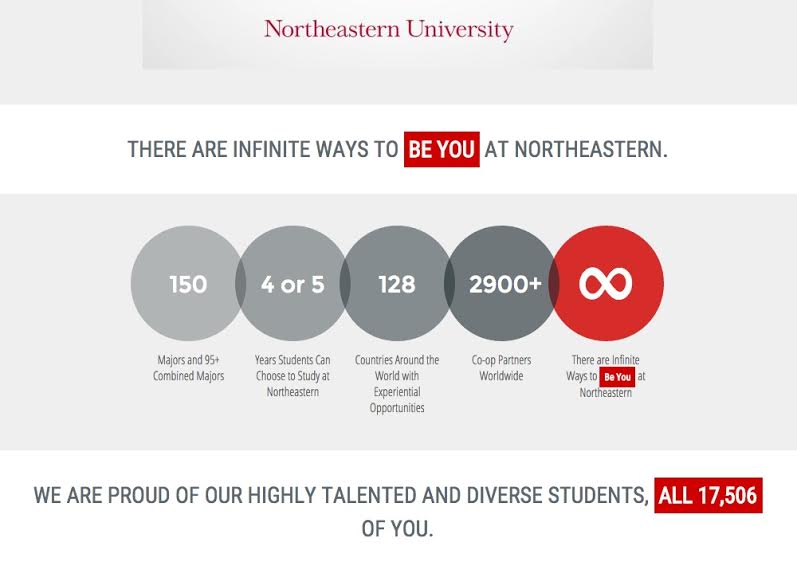

The new Title IX mandate is the bare minimum requirement for colleges and universities, establishing what they must and must not do rather than what they should do. It leaves flexibility for institutions to tailor their policies to their campus’s culture and issues. In September, Northeastern used that flexibility to publish an updated Title IX policy that aims to return its standards to those of the Obama era. It added informal resolution mechanisms—like mediation—for student-to-student allegations. It also permits both parties to retain private advisors for help during hearings.

Furthermore, Northeastern adopted its Policy on Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment to address conduct outside Title IX’s current scope. For example, Section II of the policy extends the school’s definition of sexual harassment to include unwelcome sexual conduct severe enough that it effectively denies the victim equal access to education and activities. In practice, this returns the definition to what it was under Obama-era regulations.

The university now addresses sexual or gender-based violence cases that occur off-campus—including abroad—and allegations against those not affiliated with the school. These policies are particularly essential for an institution in a city with numerous colleges and universities and with substantial travel opportunities for students.

Northeastern’s policies are largely the same as they were four years ago, with the notable exceptions of live hearings, cross-examination, and uniform evidentiary standards for different types of behavioral hearings including Title IX. These policies still have holes in them; for instance, Northeastern allowed a perpetrator to transfer during their appeal in 2011. More recently, it allowed an alleged assaulter to graduate despite pending Title IX charges.

That said, Northeastern’s enforcement problem remains the biggest obstacle for survivors seeking justice.

Northeastern has a tumultuous history with sexual assault and harassment that cannot be resolved without properly considering campus culture and administrative response. During the 2015–16 school year, the university prevented a student from being a complainant in her own case, telling her she could only serve as a witness while campus police would serve as the complainant. This atypical move meant that the student could not present the same “evidence, witnesses, and character references as the alleged assailant.” She also wasn’t allowed to access her own police report, even though the alleged assailant was.

Northeastern’s mishandling of this case was not an isolated incident. In 2011, a student alleged that she was raped by another student. According to a complaint she filed with the DoE, Northeastern administrators “discouraged her from reporting her assault and failed to inform her of her rights.” Though the hearing was scheduled for a date more than four months after her report, the student wasn’t given important written testimony until the day before. The hearing was adjudicated by “untrained undergraduates” who allowed her assailant to directly question her.

Despite these unfair obstacles, the assailant was found responsible for sexual assault. But the school allowed him to remain on campus until the end of the semester before enforcing sanctions. It was only two years later—after pressuring the school for information—that the victim discovered the assailant had successfully argued for an appeal and transferred from the university.

“Being raped was horrible, but in the end, that’s not why I left [the school],” she said later. “It was the way Northeastern treated me.”

In 2014, the DoE investigated Northeastern for Title IX violations along with eighty-four other institutions, determining that the university would need to amend its Title IX policy to ensure “prompt and equitable resolution” of complaints, as well as properly train all employees responsible for implementing the policy.

As Northeastern’s new policy is largely similar to the old one, it will likely entail the same shortcomings in enforcement. Sticking to it won’t address the institutional failures that have plagued our campus for decades and hurt so many survivors. The university’s policies alone cannot prevent it from mishandling cases; in many ways, the university’s policies have in fact been the reason for mishandling. When the university suppresses a survivor’s complaint or fails to properly investigate an allegation, it denies that survivor a just trial and shields their assailant.

The university’s inconsistent enforcement of Title IX makes fair adjudication a privilege, not a right. Considering Northeastern’s emphasis on consistency in policy, its inconsistent application is glaring. Until the university recognizes and treats Title IX as a right, survivors are forced to gamble on privilege and hope for a fair process.