Photo by Sydney Kornegay

On May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officers brutally murdered George Floyd, sparking mass outrage and protests across the United States and around the world.

These demonstrations are not just about Floyd; they’re about all of the victims who have died due to the systemic racism that built this nation. The history of police brutality that stems from our country’s founding—exploiting slaves and Native Americans—has ingrained a legacy of violence towards people of color, particularly Black people. The continuous state-sanctioned abuse Black Americans endure reminds the world of the widespread inequality present in a nation that prides itself on being the land of the free.

As protesters continue demanding police accountability for countless victims, the connective powers of social media mobilize demonstrators during a global pandemic and disseminate valuable information and resources.

#BlackLivesMatter and #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd

In recent weeks, Black Lives Matter (BLM) has coordinated many demonstrations nationwide alongside countless local activists and organizers. Founded in 2013 by three Black activists, BLM is an international human rights movement dedicated to eradicating White supremacy and amplifying the voices of Black communities. The movement—referred to both by its name and namesake hashtag—was created in response to the unpunished murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin.

Since then, #BlackLivesMatter has become a key player in the movement against police brutality and targeted violence; it has organized, mobilized, and raised awareness in the pursuit of justice. In 2014, the movement gained further momentum following the murder of Eric Garner by an NYPD officer. The officer placed Garner in a chokehold and ignored the eleven times Garner gasped, “I can’t breathe.” Less than a month later, BLM organized its first demonstration in Ferguson, Missouri after a White police officer murdered an unarmed eighteen-year-old, Michael Brown.

The movement deployed a massive number of participants and resources on the ground; it also operated as an online campaign, messaging and educating citizens. Social media played a pivotal role, allowing BLM to raise awareness and create spaces for conversation. It also helped the organization increase the number of demonstrators.

In the age of new media, meme pages and Facebook groups direct political engagement and facilitate the organization of demonstrations with unprecedented capacity.

“Within this last week, we have seen a situation that helps us understand exactly how critical social networking platforms have been to the loosely affiliated network of people who consider themselves part of the Black Lives Matter movement,” explains Meredith Clark, assistant professor at the University of Virginia and distinguished researcher on the intersection of race, media, and power.

Clark notes that social media not only disseminates valuable information and aids in organization on the ground, but also connects individuals who are separated physically or socially from the action.

Photo by Simon Brubaker; Cleveland, Ohio

In addition to social media, smartphone video capabilities have changed the conversation around accountability, as most of these murders would not have been brought to light if not caught on camera and uploaded to social media. This gives the power of broadcasting real-time action to users, who share unfiltered events straight from the source.

Diminished Trust

Americas are losing trust in traditional news outlets and their ability to accurately cover pivotal issues. To fill the information gaps created by the structural limitations of traditional media, people are turning to crowd-sourced, peer-vetted information on social media. Now, people share and vet information in real time with the swipe of a finger or the start of a livestream.

“Newsrooms are increasingly more White and male, which produces a certain kind of bias of information under the mask of more objectivity,” explains Elle Rochford, a PhD candidate at Purdue University focused on inequality, social movements, and social media. “We want our news to be coming from sources that we trust and we increasingly don’t trust people in charge, particularly on issues like Black Lives Matter.”

Racial stereotyping presents a significant barrier to accurate reporting by shifting the coverage of race relations. Conservative media outlets have labeled the mostly peaceful ongoing protests as unlawful riots; yet, when White protesters demonstrated against lockdown orders, the same correspondents expressed empathy. Given this reality of racial bias, it is imperative that news consumers turn to Black voices when educating themselves on Black issues.

“I feel as if young people have an immense distrust of the media in terms of accurately reporting and portraying what is truly occurring on the front lines,” adds Shakaa Chaiban, a third-year African American Studies major at Wesleyan University. “To be quite frank, I feel as if mainstream media outlets will never have the ability to provide unfiltered, raw coverage of the truth of what’s happening on the ground, and social media has instead become a vehicle of providing true footage, coverage, and reporting.”

Chaiban has been distributing snacks, first aid, and essential personal protective equipment in his home borough of Brooklyn. The organizing and funding for these supply runs was facilitated through social networking channels.

“For our protest supply runs, social media has been incredibly useful and efficient in both informing people around Brooklyn of our whereabouts, where we will be distributing our supplies and resources, and to reach various demographics and audiences to get donations through Instagram and Facebook,” explains Chaiban.

Photo by Simon Brubaker; Cleveland, Ohio

Due to the global pandemic, communities worldwide have restructured themselves around online communication channels; consequently, users are growing more efficient in operating these platforms and spreading information within them.

“Social media has been so important in general and then for this latest murder to happen at a time of pandemic and social distancing . . . I think it made the social media effect even stronger because people were almost completely online,” explains Rachel Einwohner, a professor of sociology at Purdue University focused on the dynamics of protest and resistance. “Social media absolutely has the power to allow people to politically engage in ways that they can’t for health reasons or curfew reasons. If you have to be inside for curfew you can still be tweeting all night.”

Social networks lower the barrier to entry, enabling increased participation and inclusion for groups or people that would have otherwise been excluded from the conversation. Now, people can spread peer-reviewed information—on getting involved, handling tear gas, or donating to community organizations and victim family funds—that isn’t typically found in mainstream coverage.

Clark specifies that peer review on social media is very different from academic peer review.

“Peer review in academia [is] generally blind, you don’t know who the peer reviewer is, it’s just this expectation that they have the experience and the perspective to analyze the information that you’ve presented to them,” Clark observes. “On social media, what you have is people building on the networks of relationships that they have made over the years. So you have trust within some of these networks.”

Social media has also boosted visibility of Black voices through countless user accounts, hashtags, and even internet ephemera like memes. This allows Black Americans and citizens around the world to shape the conversation around police brutality and much-needed reform, without having to navigate the structural barriers to candid racial analysis existent in traditional media channels.

“The structures that are in place in news media make it very difficult for the public to get a clear understanding of what some of the objectives and goals of the [Black Lives Matter] movement are,” explains Clark. Institutional biases and corporate interests can cloud the information that traditional media outlets share.

While legacy media institutions play an essential role in summarizing social movements to readers and viewers, their long-established standard of journalistic objectivity limits their coverage. It can pressure them to frame movements for basic human rights—like Black Lives Matter—as partisan issues. As journalists, we don’t consider the fight to end hunger to be a partisan issue. The murder of Black and Brown people is no different.

Photo by Sydney Kornegay

Journalists working for major news networks are often sequestered at demonstrations and cannot reach the heart of the action. Because of these obstacles, they turn to user-generated content to fill information gaps and contextualize movements.

“I think the public erosion of trust in larger [media] institutions has really contributed to this,” notes Rochford. “Do you trust a large corporation—where you don’t know anyone—more, or do you trust the bail fund that your friend is circulating?”

Streamlining: Memes, Hashtags, Peer Review

Efforts online are efforts on the ground––the two are intrinsically tied and play equally valuable roles in any social movement. In the fight against racial inequality and police brutality, social media users report online what happens on the ground, facilitating conversation and boosting attendance.

“[Black Lives Matter] was born out of on-the-ground activists. And I think there’s this tendency to view online activism as different and separate from on-the-ground activism when it’s largely on-the-ground activists that drive these hashtags, that do the organizing,” explains Rochford. “The hashtags aren’t detached from the bodies on the ground. And a lot of the content coming out right now as part of these protests are people on the ground live streaming. That’s where these images are coming from.”

In addition to real-time content and information sharing, the circulation of flyers and handouts has historically played a significant role in organizing. This moment is no different. As memes replace traditional cultural artifacts, they act as easily digestible vessels of social commentary and an instrumental aid for many in understanding social issues.

“There’s ephemera in every social movement and it’s part of the materiality of voicing a message that is easily lost. During the Civil Rights Movement people printed out handbills and printed out flyers and we still do that sort of stuff today, but so much more of it is digitized,” explains Clark.

“Memes are so easy to create and to mark up but they’re also so quickly forgotten. And you think about how a meme in a moment can entertain, it can provide some levity, it can even provide some fuel for action. But unless we are finding really effective ways to preserve it, we are going to lose the importance of how these smaller things played a role in the movement.”

Memes and meme accounts occupy a unique and important space in contemporary culture, mobilizing people in unprecedented ways. They can shift the conversation around social issues, spread information, and promote tangible actions like signing petitions for law enforcement accountability or donating to related funds.

Patia Borja started her widely popular Instagram meme page as a space to share candid, relatable content and commentary with friends, while reclaiming the Black vernacular appropriated by White-run accounts. Black-founded and curated, the once-private @PatiasFantasyWorld has over a hundred thousand followers and shares a wide range of memes including complex social commentary codified in text-based jokes. A hilarious, occasionally raunchy community center of sorts, the page is a dedicated space for Black voices.

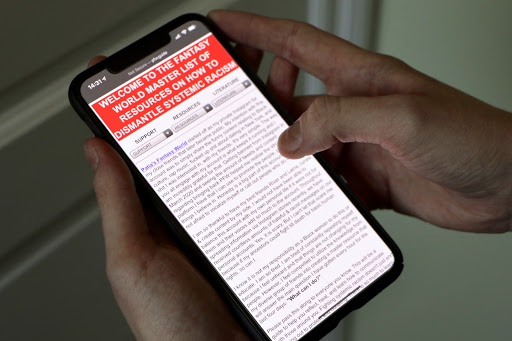

In response to Floyd’s murder, Borja has been using the profile—which she manages with her friends River and Laina—to spread valuable information about efforts on the ground and the ways users can support the movement. She also created the Fantasy World Master List and mobile site, a database of virtually every resource one would need to engage with the movement to dismantle systemic racism. And it has been spread to every corner of the internet using a meme account.

“I thought it was important to have a central place for everything,” explains Borja. The list compiles everything from educational materials and literature to bail funds and GoFundMe accounts.

Borja expressed that she hoped to expand visibility for further-marginalized groups when integrating resources, including those relating to Black LGBTQ+ people or mental health resources: “I think that’s what also kind of led to the database. I was like this is a meme account run by a Black woman. And I’m gonna do this.”

“I think we’re going to add on emergency pages, like things to remember before you go protest. Numbers, know your rights. I wanted the mobile site to be in your pocket, everything you need to know,” she added.

Just like memes, the demonstrations are constantly changing. Resources and information adapt accordingly.

“This shit moves fast. Even thinking about this database, I was in a kind of meme headspace of ‘this is something that’s going to have to be constantly updated,’” Borja notes. “I have created something that I have to keep working on because this thing is a constant––racial inequality is such a constant battle no matter what. Everyone who is not White faces this, in this country especially.”

Borja also notes how the interconnected nature of culture, humor, and politics online contributes to how people engage with information as events occur in real-time.

“I think that’s something super powerful about social media, that people want to think that it’s all about this negativity and drama online, but it is the most useful tool we have because we need to have real time information,” she explains. “We’re not sitting at home watching CNN all day.”

High-profile meme accounts and small personal accounts can play a role in verifying sources and spreading vital information. On Blackout Tuesday, users—attempting to create a day of visibility—posted black squares in solidarity with BLM; however, their actions inadvertently worked against the movement by clogging integral hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter and #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd. Furthermore, the trend allowed users to passively participate by doing essentially nothing while feeling the gratification of “taking a stance” in the name of racial equality. Once people became aware of the harm in these actions, they implored users to take down these posts and untag them. The response was immediate and efficient.

Double-Edged Sword: Internet Guide to Staying Safe While Protesting

From updates and announcements on demonstrations, to methods for getting tear gas out of your eyes, to tips on protecting yourself from being targeted by law enforcement, activists have turned social media into a comprehensive protesting resource. Not surprisingly, much of this information is being shared by protesters in Hong Kong or others who have dealt with state-sanctioned violence in response to protest. Legal advice including numbers to call if you’ve been arrested, links to bail funds, and know-your-rights compilations are disseminated en masse, in unprecedented quantities.

People often overlook the danger of communicating using third-party platforms. This includes social networking apps and even text messages through your service provider.

“Anything you say on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, even Discord, Slack—those companies respond to subpoenas immediately. They will turn over your Discord chat tomorrow,” explains Andrew Schriver, an assistant public defender for Medina County in Ohio. “Social media is good for getting things out there, getting an event out there, but it’s very bad for planning anything because the retribution’s immediate . . . All [of] these companies no matter how good of a game they happen to be talking at the time, they will turn your stuff over tomorrow.”

Many individuals are exposed to criminal liability when private and personal information can be shared with law enforcement officials upon request. This is dangerous, especially when written text is taken out of context, as obvious jokes could be weaponized.

“You have to imagine whatever you’re saying on social media being read without context in a very flat format to a jury . . . Some federal prosecutor is going to stand up in a suit and read that in a very serious voice to twelve people who don’t have the context, as a way to prove that you were intending to cause a riot,” explains Schriver. “If you turn over any information to a third party, they’re allowed to turn it over to the police and you don’t have a Fourth Amendment right to that information anymore.”

“The value of Signal and Telegram and things like that, is that they’re encrypted end-to-end,” Schriver adds. Because they’re run by people who are either based overseas or are wholly dedicated to protecting privacy in communication, these companies won’t respond to American subpoenas.

Largely taking cues from protesters operating under restrictive regimes, many users implore protesters to turn off location services, download encrypted messaging apps, and avoid sending information about demonstrations online.

The inability of the Supreme Court to update privacy laws and adopt them to the communication standards and methods of the digital age “exposes a lot of people to a lot of criminal liability,” explains Schriver. “So you Signal everybody.”

It Doesn’t End There: Defunding and Looking Forward

After two weeks of global protests against police brutality, federal and state governments are buckling. As a result, states and cities—including Minneapolis—are banning chokeholds, neck restraints, and tear gas. Colorado’s Senate passed a law tackling police accountability, and Michigan’s Senate passed a training bill aimed at reducing police brutality. At the federal level, Democrats in Congress have unveiled a sweeping bill that targets police misconduct and racial bias, restricts the use of deadly force, and curtails protections that shield law enforcement officials from accountability.

Campaigns to defund and disband police departments have also garnered significant support and sparked action. New York City mayor Bill de Blasio vowed for the first time to cut NYPD funding, while Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti slashed $100–150 million from the LAPD budget. Most recently, Minneapolis City Council members pledged to disband the Minneapolis Police Department and invest in community-led public safety in what seems like a viable step in the right direction.

All of this was achieved in two weeks. Imagine what can be achieved three weeks out. Or four.

Social media isn’t revolutionizing anything. It’s one more tool participants can use, one more method of organization at our disposal. But the only way to revolutionize anything is to get involved. Donate. Participate. Get on the ground. Read, educate yourself and those around you. Boost Black voices. Be an ally. Show up in solidarity, not to pursue your own agenda. Listen to Black and Brown people.

Don’t let action wither because time has passed. Don’t be insensitive and post pictures of brunch when people are on the ground fighting for the right to live without fear, for the right to live, period. Stop appropriating Black culture and pretending to care just for appearances. Be the change you want to see. And don’t stop until tangible reform follows, because it only will with persistence.

“You think about the various intersecting oppressions that exist in this world. You realize that yeah, we might make some major changes in 2020 and the next three to four years, but there’s still so much more that will have to be done,” explains Clark. “Freedom. Angela Davis said it well: ‘Freedom is a constant struggle.’ And it requires that in every generation, and even in every day, we continue to work towards the goal of being free.”