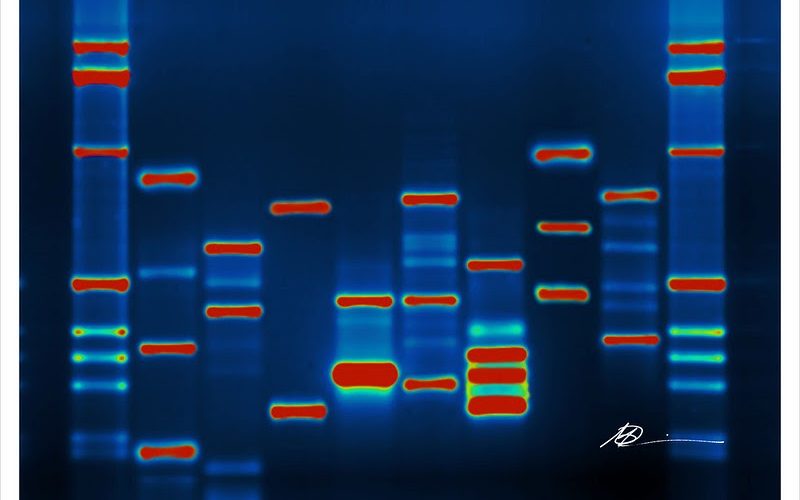

The dawn of genetic testing has allowed scientists to see patients’ entire DNA sequence and identify any changes in that sequence that could cause disease. Genetic testing and sequencing is expected to become commonplace in primary care within the next few years. Genetic screening is also used in oncology and in the context of reproductive and family planning.

As the use of this technology increases, it becomes increasingly important to understand how this will affect patient health and outcomes. There have been several studies examining the effects of genetic sequencing on medical practice. However, sequencing projects that have been touted as groundbreaking had one unifying problem: in most cases, over 80 percent of participants were white and reported a household income of greater than $100,000 a year.

This has resulted in a troublingly skewed pool of sequenced human genomes. Researchers commonly share de-identified patient genetic sequences for collaborative use. If a group discovers a mutation that they believe causes disease, they consult this pool of shared genomes to see if the mutation is widespread. This pool is used both as a control against their results and to see if other patients who had this mutation had the disease of interest. However, this homogenous set of genomes has proved problematic.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016 uncovered that 74 percent of the most commonly seen mutations thought to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy—abnormal, sometimes life-threatening thickening of heart muscle—were actually benign. The authors reanalyzed these genomic variants and found that those that were most common in the general population were overrepresented in African Americans. Simulations revealed that this misclassification could have been avoided if even small numbers of African Americans had been included in original studies. Many patients—if they were found to have these variants—received troubling diagnoses that could have been avoided if a more diverse control population had been included in the original study.

Some studies have examined how patients view genetic testing and their perceptions about testing they have received. In a 2019 study, twenty Latina patients were interviewed about their understanding of genetic testing in the context of breast cancer risk. The most common topics patients brought up included a lack of information about genetic testing services as well as difficulties in obtaining health care. However, patients saw genetic services as positive even though many reported a lack of cultural sensitivity when seeking them out. This small sampling shows that although barriers to genetic testing exist, it is seen as a positive resource and many patients would be open to receiving it if it were more readily available.

Genetic studies that do focus on minorities tend to narrow their scope to focus on only one disease. Broader studies have listed a lack of racial and socioeconomic diversity as an experimental limitation, but did not tailor their recruitment processes to prevent this issue.

A comprehensive review of research metadata found that out of the 110 million patients who participated in genetic research from 2005 to 2016, only 2.4 percent were of African ancestry, compared to 78 percent with European ancestry. This is a twofold problem; some African American patients are unwilling to participate in research, and researchers are not changing their recruitment processes to reach diverse patient populations.

There is context as to why patients of color may be hesitant to participate in medical research. A survey conducted in 2018 reported that non-white participants cited worries about government and police use of data for discriminatory purposes more often than whites.

Several past studies have reported that patients cite a fear of further racialization of genetic information, mistrust of the medical system, and lack of education as the largest deterrents. Genetic information is becoming racialized as more genes that contribute to physical appearance or race/ethnicity dependent traits are discovered. However, a study of African American mothers showed favorable perceptions of genetic testing, and other studies have shown racial minorities’ positive attitudes towards genetic testing if the services were more readily available.

Historically, medical researchers have used Black patients’ bodies without their consent. This has been famously documented by stories such as that of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were taken without her consent during her cancer treatment and used to form the first infinitely reproducing cell line. This led to numerous medical advancements and changed the way cellular research is performed, however her family did not find out about her role until decades after she died.

A more notorious example is that of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which was conducted from 1932 to 1972 by the US Department of Public Health. Hundreds of syphilis-infected Black men were denied treatment to cure the disease so that researchers could observe how it progressed. Is it surprising that African American patients are hesitant to participate in research today?

Understandably, African Americans are less likely than white Americans to report trust in their health-care providers. This distrust is founded in modern day realities: Black patients are 25 percent more likely to die of cancer than white patients, and tend to develop chronic disease earlier in life and have shorter life expectancies. This discrepancy is due to a lack of access to quality medical treatment. Studies have shown that Black patients are less likely than white patients to be prescribed newer medicine that has fewer side effects, and their symptoms are more often reported as less serious than those of white patients. This, among other factors, discourages African American patients from seeking care, as they do not believe their doctors will hear them.

For some lower-income patients the possibility of some insurance discrimination based on their genetic test results is a concern as well. This type of discrimination is legal in the United States, which lags behind other countries in protecting patients from genetic discrimination by all types of insurance companies. The 2008 Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act is the most comprehensive federal legislation, however it only protects patients from discrimination by health insurers and employers. This loophole leaves patients open to discrimination from life, disability, and long-term care insurers and can greatly affect insurance costs and options available to patients and their families.

This vulnerability has made patients more hesitant to participate in research that involves genetic testing, and may lead to decreased sample sizes. Forty-two independent studies have reported considerable concern about insurance discrimination from patients regarding genetic testing. It’s likely that this would apply disproportionately to patients of color, as most forms of discrimination do.

More efforts must be made to increase diversity in future studies by changing recruiting practices to tailor to patients of color. This can include having interpreters and recruiting in hospitals that serve more diverse populations. Research assistants can be trained to be more open and approachable, as well as providing supplemental information to patients with less background knowledge of genetics.

Research is often the first step to changing medical practices. If the patients recruited for research do not accurately represent the patient population, these results are essentially useless for the groups excluded during research. We will never know how the ever-changing medical landscape affects marginalized communities if scientists are not including them in their research about these changes. In order to make not only genetic research, but all medical research, more accurate and equitable, we must include everyone.