On November 2, 1972, Monty Python aired their seminal sketch “Argument Clinic,” in which a man enters said clinic seeking, as hard as it may be to believe, an argument. The receptionist directs him to a room where the inexplicably named Mr. Vibrating awaits him.

The man asks whether he’s in the right room; Mr. Vibrating counters that the man was already told this. The man says he hasn’t been informed, kicking off a repetitive “no you didn’t/yes I did” exchange. The man grows frustrated:

Man: Oh look, this isn’t an argument.

Mr. Vibrating: Yes it is.

Man: No it isn’t. It’s just contradiction.

Mr. Vibrating: No it isn’t.

Man: It is!

Mr. Vibrating: It is not.

Man: Look, you just contradicted me.

Mr. Vibrating: I did not.

Man: Oh you did!!

Mr. Vibrating: No, no, no.

Man: You did just then.

Mr. Vibrating: Nonsense!

On September 26, 2016, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton squared off in the year’s first presidential debate at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York. About seventy minutes in, Trump evaded moderator Lester Holt’s question about domestic terrorism by pivoting to America’s Middle East presence, causing this exchange:

Clinton: Donald supported the invasion of Iraq.

Trump: Wrong.

Clinton: That is absolutely . . .

Trump: Wrong.

Clinton: Proven over and over again.

Trump: Wrong.

Seem familiar?

This contradiction lasted six seconds and accomplished nothing. The candidates wandered from Holt’s question. Trump repeatedly interrupted Clinton. Nothing was established regarding Trump’s position on America’s invasion of Iraq (he supported it).

The same can be said of an exchange seventeen minutes earlier in the debate, when Holt mentioned that “stop-and-frisk was ruled unconstitutional in New York because it largely singled out black and Hispanic young men.”

Trump: But stop-and-frisk had a tremendous impact on the safety of New York City. Tremendous beyond belief. So when you say it has no impact, it really did. It had a very big impact.

Clinton: Well, it’s also fair to say, if we’re going to talk about mayors, that under the current mayor, crime has continued to drop, including murders. So there is . .

Trump: No, you’re wrong. You’re wrong.

Clinton: No, I’m not.

Trump: Murders are up. Alright. You check it.

Clinton: New York, New York has done an excellent job.

Again, nothing is established. Again, the candidates cut each other off. Again, Trump is wrong.

A record eighty-four million people watched this debate, according to Nielsen tracking. The actual figure is undoubtedly higher because Nielsen doesn’t count live streams or people watching at bars, restaurants, parties, offices, and other gathering places. Though debate viewership as a percentage of the voting-age population declined between 1980 and 1996, it has rebounded since, with the Internet providing a new medium more appealing and accessible to younger viewers.

Presidential debates, as the only direct exchanges between candidates, shape the elections they precede. But previous debates, particularly the 2016 Clinton–Trump contests, reveal flawed structures, rules, and practices.

Let’s fix them.

“Sir, that’s the facts”

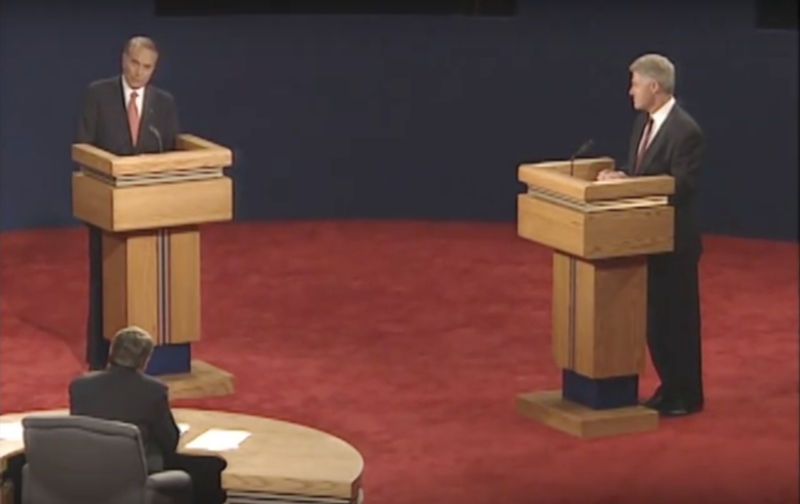

Democrat Bill Clinton debates Republican Bob Dole in 1996. PBS’ Jim Lehrer moderates.

“I am honored to have this role,” Holt said to begin the first 2016 debate. “But this evening belongs to the candidates.”

“I do not believe it is my job to be a truth squad,” third-debate moderator Chris Wallace remarked. “It’s up to the other person to catch them on that . . . I want it to be about them.”

Both are espousing the traditional moderator role: getting out of the way so the candidates can debate each other. There are legitimate concerns regarding active moderators, chiefly that the vast knowledge and split-second decision-making required to fact-check a debate is impossible for one person.

The second presidential debate of the 2012 election justified these concerns. Moderator Candy Crowley asked about the previous month’s attack on American government facilities in Benghazi, Libya. When Democratic nominee Barack Obama said that he had referred to the incident as an act of terror the next day, Republican nominee Mitt Romney claimed it had in fact taken the president fourteen days to refer to it as such. Then:

Obama: Get the transcript.

Crowley: It — he did in fact, sir. So let me — let me call it an act of terrorism . . .

Obama: Can you say that a little louder, Candy?

Crowley: He did call it an act of terror. It did as well take — it did as well take two weeks or so for the whole idea of there being a riot out there about this tape to come out. You are correct about that.

Romney: This — the administration — the administration (APPLAUSE) indicated that this was a — a reaction to a — to a video and was a spontaneous reaction.

Crowley: They did.

Romney: It took them a long time to say this was a terrorist act by a terrorist group and — and to suggest — am I incorrect in that regard? On Sunday the — your — your secretary or . . .

Obama: Candy . . .

Romney: Excuse me. The ambassador to the United Nations went on the Sunday television shows and — and spoke about how this was a spontaneous reaction.

Obama: Candy, I’m — I’m happy to . . .

Crowley: Mr. President, let me — I . . .

Obama: I’m happy to have a longer conversation about foreign policy.

Crowley: I know you — absolutely. But I want — I want to move you on.

Obama: OK, I’m happy to do that too.

Crowley: And also, people can go to the transcripts and . . .

Obama: I just want to make sure that . . .

Crowley: . . . figure out what was said and when.

Unpunctuated legalese might be easier to understand. Crowley’s post-debate remark that Romney was “right in the main” didn’t clarify things.

Another exchange, pulled from a 2015 Republican primary debate, sees CNBC moderator Becky Quick lose control after a less-than-confident attempt to fact-check then-candidate Trump.

Quick: Mr. Trump, let’s stay on this issue of immigration. You have been very critical of Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook who has wanted to increase the number of these H1Bs.

Trump: I was not at all critical of him. I was not at all. In fact, frankly, he’s complaining about the fact that we’re losing some of the most talented people. They go to Harvard. They go to Yale. They go to Princeton. They come from another country and they’re immediately sent out. I am all in favor of keeping these talented people here so they can go to work in Silicon Valley.

Quick: So you’re in favor of . . .

(CROSSTALK)

Trump: So I have nothing at all critical of him.

Quick: Where did I read this and come up with this that you were . . .

(CROSSTALK)

Trump: Probably, I don’t know — you people write the stuff. I don’t know where you . . .

(LAUGHTER)

(APPLAUSE)

After an unprompted, vague, rambling 200-word tangent from Trump on his campaign funding and the dangers of Super PACs, Quick tried to redirect him.

Quick: You know, Mr. — you know, Mr. Trump, if I may (inaudible). You’ve been — you have been — you had talked a little bit about Marco Rubio. I think you called him Mark Zuckerberg’s personal senator because he was in favor of the H1B.

Trump: I never said that. I never said that.

Quick: So this was an erroneous article the whole way around?

Trump: You’ve got another gentleman in Florida, who happens to be a very nice guy, but not . . .

Quick: My apologies. I’m sorry.

(CROSSTALK)

Trump: . . . he’s really doing some bad . . .

(CROSSTALK)

Marco Rubio: Since I’ve been mentioned, can I respond?

(CROSSTALK)

Quick: Yes, you can.

Quick had the facts, but wasn’t confident enough in her knowledge to adequately check Trump’s lies. She and fellow moderators Carl Quintanilla and John Harwood were criticized for clashing with and talking over the candidates, as well as not challenging false assertions.

Ever since moderators assumed a bigger questioning role in 1996, many journalists have argued that they aren’t equipped to fact-check quickly and accurately. Crowley and Quick’s performances—and a 2015 Annenberg Public Policy Center focus group that complained the moderators “tend to take sides, giving one of the candidates an edge”—seem to indicate that moderators cannot hold candidates accountable.

But they can, and they have to.

Trump lied his way to the presidency. His time in office hasn’t indicated that his re-election campaign will be any different. Calling out untruthful candidates has become more important as some of them openly spread misinformation. Moderators must be empowered to overcome the quickness and accuracy constraints of a live debate.

The network broadcasting the debate could staff the telecast with fact checkers. These fact checkers would prepare notes on likely matters of factual contention, particularly claims that candidates have frequently made while campaigning. The debate against Clinton was not the first time Trump made a false claim about his Iraq viewpoint, making it an ideal lie to quickly dispel with tens of millions of people watching.

The moderator would assign each fact checker an area of facts and candidate statements to study before a debate. The moderator wouldn’t need to know all the information, just what information is available. The moderator can then call for a fact check when necessary. If the information comes via video or graphics for easy viewer digestion, even better.

Enter Chris Wallace. On March 3, 2016, Wallace was one of three moderators of a FOX News Republican primary debate. He asked Trump about his comments on reducing the size of federal agencies; Trump responded by saying he’d reduce the Department of Education and the Environmental Protection Agency. Then:

Wallace: But Mr. Trump, your numbers don’t add up. Please put up full screen number four. The Education Department, you talk about cutting, the total budget for the education department is $78 billion. And that includes Pell grants for low-income students and aid to states for special education. I assume you wouldn’t cut those things. The entire budget for the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency, $8 billion. The deficit this year is $544 billion. That’s more than a half-trillion dollars. Your numbers don’t add up, sir.

Trump: Let me explain something. Because of the fact that the pharmaceutical companies — because of the fact that the pharmaceutical companies are not mandated to bid properly, they have hundreds of billions of dollars in waste. . .You are talking about hundreds of billions of dollars . . .

Wallace: No, you are not.

Trump: . . . if we went out to the proper bid. Of course you are.

Wallace: No, you’re not, sir. Let’s put up full screen number two. (APPLAUSE) You say that Medicare could save $300 billion a year negotiating lower drug prices. But Medicare only spends $78 billion a year on drugs. Sir, that’s the facts.”

Trump: I’m saying saving through negotiation throughout the economy, you will save $300 billion a year.

Wallace: But that doesn’t really cut the federal deficit.

Trump: And that’s a huge—of course it is. We are going to buy things for less money. Of course it is. That works out . . .

Wallace: That’s the only money that we buy—the only drugs that we pay for is through Medicare.

Though this exchange may have happened because FOX News owner Rupert Murdoch instructed his moderators to target Trump, it doesn’t disprove the larger point: moderators can, through intent, preparation, and effective presentation, fact-check candidates in real time. Fact checkers should prioritize information from reputable sources, including government-gathered data, peer-reviewed research, and accurate, fair-minded news organizations. In an ideal world where candidates spoke truthfully about their actions and the effects of implemented and proposed policies, moderators could lean back and let the debate unfold. We do not live in that world. Journalists’ first priority is adherence to the truth; they cannot abdicate it with tens of millions of people watching.

“The rules are your friend. Use them so this doesn’t become a debate.”

President Barack Obama prepares for a 2012 debate. Senator John Kerry stands in for Obama’s opponent—Republican Mitt Romney—in rehearsal.

On November 6, 2005, NBC’s The West Wing aired an episode depicting the sole debate between the show’s presidential candidates—Republican Arnold Vinick and Democrat Matthew Santos.

Both candidates chat with top campaign personnel before walking on stage. Vinick refers to the agreed-upon rules as “stupid” and says that they limit him. Santos is told, “The rules are your friend; use them so this doesn’t become a debate.”

After both candidates take their places behind their podiums, the moderator explains the rules—two-minute answers, one-minute rebuttals, and a thirty-second rebuttal to the rebuttal at the moderator’s discretion. Vinick shakes his head during the recitation of the rules, drawing a laugh from the audience.

Vinick begins his prepared opening statement, pauses, and pivots. Citing the famous Abraham Lincoln–Stephen Douglas debates of 1858, he argues that the rules prohibit real, substantive discussion. He invites Santos to debate freely with him, with the moderator asking questions and ensuring fairness. Santos accepts.

The debate is a lively, informative one, built around a fully free exchange of ideas and candidates holding each other to answers. Despite some audience noise and candidate interruptions, it succeeds; voters understand the candidates’ positions on the issues.

The show broadcast the debates live, once each for the East and West Coast. That, plus the casting of real journalist Forrest Sawyer as the moderator, gave the episode the feel of a real debate. But the similarities between that debate and our reality end there. The West Wing was concentrated political idealism, arguably one of the reasons it resonated with viewers. It showed what could be accomplished when two knowledgeable, principled, reasonable, and respectful candidates engage in a civil exchange of ideas.

But in our world Donald Trump brags about his penis during debates, so let’s talk format.

Format is a broad term, encompassing the debate’s setting and rules. Typically, debates are divided into six fifteen-minute sections. Each section focuses on a topic chosen by the moderators, with questions asked either by the moderator or by undecided voters in a “town hall” style. Each section begins with two-minute answers by each candidate, followed by ten or eleven minutes of open discussion.

In the chess clock format, each candidate has forty-five minutes of speaking time, which is displayed on a clock. The moderator prepares a list of eight topics which are given equal time. Once the moderator introduces a topic, any candidate can respond, but they must hit their clock before speaking. Candidates can seize the floor at any time by hitting the clock, though they cannot hold the floor for longer than three minutes. Their clock counts down as they speak, and once a candidate’s time is exhausted they cannot speak anymore, even to give a closing statement.

The chess clock format promotes direct exchange between the candidates, who must hold each other to answers and truthful statements. Instead of trying to prevent interruptions, the chess clock accepts and formalizes them.

It also allows debaters discretion over how they use their time. Currently, a candidate must speak at equal length on every topic; with the chess clock model, they could allot more minutes to topics on which they have strong feelings, or issues that play into their strengths or their opponent’s weaknesses. This encourages them to move beyond their campaign stump speeches to more detailed, substantial answers. Candidates also wouldn’t have to speak for two minutes if they didn’t have two minutes’ worth of points to make.

But allowing unlimited interruptions would encourage candidates to shout over one another even more than they do now.

The reformed standard model more closely mirrors the current format, but with a few differences. Each candidate is allowed two “points of personal privilege” or “challenge flags.” These allow them to deviate from the format to clarify responses or respond to attacks when the format wouldn’t otherwise allow it. This model also slightly alters the answer–rebuttal times and changes the way questions are picked, allowing for candidates, the moderator, and the public to each select several questions.

Both models address some structural problems and ignore others. The following model combines the best of both.

- Split the debate into six fifteen-minute sections. The public and the moderator choose three topics apiece. The moderator crafts the questions within each section. Each section is given equal time.

- The public’s choices are ascertained through polling on the problems that matter most to voters (Gallup’s “Most Important Problem” is one example). To ensure accuracy and transparency, pollsters must publish detailed explanations of their methodologies.

- The candidates alternate who begins a section. A coin toss determines the first speaker in the first section.

- Candidates receive equal portions of speaking time (forty-five minutes for two candidates, thirty minutes for three, and so on). They need not use all of it, but if they do they are done for the evening.

- Candidates hit the chess clock to end their speaking time. This allows them to divvy up their time as they see fit without permitting interruptions.

- Speaking turns are limited to half of the time allotted for a section (7.5 minutes) to prevent the candidate who speaks first from holding the floor for the whole section. Candidates, recognizing that long answers might bore or confuse viewers, probably won’t get near the limit.

- If all candidates are done speaking before a section’s time elapses, that section ends early. The unused time does not roll over to future sections.

- The moderator can mute the candidates’ mics if they repeatedly interrupt their opponents or the moderator, or if they continue speaking after time—theirs or the section’s—is up. The moderator can also redirect the candidates if they aren’t answering the question.

- A candidate’s clock doesn’t stop while the moderator corrects a false assertion or redirects them to answer a question. This should incentivize on-topic, truthful answers and discourage candidates from fighting the moderator.

- No opening or closing statements. They allow candidates to give rehearsed speeches, the sort they’d give during campaign stops or in TV ads. Structured debate—wherein candidates tackle questions they don’t know in advance—promotes specific, issue-driven answers and engagement with opponents.

Who and Where and Why

While Trump and Clinton exchanged barbs onstage at Hofstra University, law enforcement officials escorted Jill Stein off the campus. Some of her supporters were arrested; Stein was similarly handcuffed at the second debate in 2012. Stein’s crime: lacking event credentials.

Since 2000, the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD)—the nonprofit that has organized the events since 1987—requires candidates to poll at fifteen percent or higher in at least five national polls before appearing on the debate stage. The pre-1987 organizer, the League of Women voters, used the same standard. The two third-party candidates who registered at all in 2016—the Libertarian Party’s Gary Johnson and the Green Party’s Stein—peaked at thirteen and seven percent, respectively, and spent most of their campaigns languishing well below their polling peaks.

Supporters of third-party candidates argue that the CPD’s rules create a vicious circle that perpetuates a two-party race, that candidates seeking popularity from debate exposure are barred from debating because they aren’t popular already. They contend that their candidates could muster support by voicing their opinions and proposals to tens of millions of viewers.

The claims of restricting the race to two candidates are valid, but best directed elsewhere. As long as states assign all of their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the state vote irrespective of margin, third-party candidates suffer more from state laws than from CPD policy. As for the entry standard, perhaps something can be done.

The CPD could lower the standard to ten percent for the first debate. This is a challenging but not impossible bar to clear; it would have allowed Johnson into the first debate in 2016. The bar would be raised for subsequent contests. If third-party supporters are correct that their candidates’ popularity suffers from lack of exposure, the candidates’ first-debate showings will boost them enough to qualify them for the others. If not, the Democratic and Republican candidates can debate twice one-on-one after proving that they’re the only candidates in the race capable of winning.

But the question of participants doesn’t end with the debaters. A network journalist has moderated every debate, and there are advantages in having TV journalists do the job. They’re used to questioning candidates directly, on TV, in front of large audiences. But they’re also used to a medium prone to sensationalism, one that prioritizes the most entertaining narrative even if it’s not the most relevant or important to voters. They know how their performance affects their journalism careers and the profiles and reputations of their networks.

It could be valuable to introduce a different type of moderator, someone with appropriate knowledge, experience, and credentials who lacks a vested interest in TV stardom. Print journalists, university presidents, retired judges, historians, and professors of journalism, political science, public policy, or other humanities could succeed in the role.

The venue can also be re-examined. Since 2000, every debate has been held in a large, audience-packed hall at a college or university. Though the moderator typically entreats the audience to remain silent, the audience doesn’t always comply, and any applause, laughter, or other reaction influences the audience watching at home.

The large venues also allow for a post-debate “spin room” in which reporters cluster around campaign personnel, party officials, and campaign surrogates to get their take on the exchange between the candidates. This opinion-driven media circus can supersede fact-based coverage in the vital few minutes after the debate when the residual audience ensures high ratings.

Small venues would limit or preclude studio audiences and media not essential to the broadcast. For instance, the moderators, fact checkers, and broadcast technology personnel are essential; reporters from other networks are not. This could reduce the peripheral spectacle and focus everyone’s attention on the main event.

Pragmatic or Pipe Dream?

In the first season of HBO’s The Newsroom, the staff of the fictional Atlantis Cable News’s (ACN) equally fictional flagship show News Night staged a mock debate. The show’s producers and reporters each played one of the 2012 Republican presidential candidates.

The format—which ACN was pitching to officials from the Republican National Committee (RNC)—relied on an active moderator holding the candidates to truthful, on-topic answers. After anchor Will McAvoy questions the “candidates” in this manner for a while, one of the RNC officials halts the exercise.

“I am not allowing the goddamn press to make fools out of our candidates,” he yells. “We’re not agreeing to this format.”

The Annenberg Working Group on Presidential Campaign Debate Reform found that respondents’ biggest criticism was moderators failing to do their job, including complaints of bias, not controlling candidates, and failing to call out non-answers. But this presents an inherent contradiction: an active moderator is accused of bias, and a restrained one is faulted for not controlling the debate enough. There may be no way out here.

But this isn’t the problem with the rules proposed in this article. It’s that the candidates wouldn’t submit to it.

Candidates aren’t required to debate; they do it because they think it will boost their chances of winning. Even though candidates would play by the same rules, and a candidate who withstands tough questions looks competent and strong, they likely would be more wary of the looking bad than hopeful of looking good. The CPD would have to sell significant reforms to cautious campaigns.

The precedent here is grim. When the League of Women Voters ceded its debate sponsorship in 1988, it cited a closed-door agreement between the Bush and Dukakis campaigns that “gave the campaigns unprecedented control over the proceedings.”

The demands of the two campaign organizations would perpetrate a fraud on the American voter . . . the candidates’ organizations aim to add debates to their list of campaign-trail charades devoid of substance, spontaneity and honest answers to tough questions. The League has no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.

–League President Nancy S. Neuman

So meaningful reform remains a pipe dream. But it’s one worth dreaming.

A 2014 survey revealed that a plurality of voters considered the debates the most helpful factor in choosing a president. Though we focus on undecided voters during debate season, these events can also change the minds of supposedly decided voters.

The Lincoln–Douglas debates may indeed be the stuff of history books and nothing more. Mass media and the Internet may not allow for them. But that doesn’t necessarily mean we can’t have debates of that caliber.

Debates can tell voters how candidates will do the job. They can expose candidates with an insufficient grasp of world events and public policy. They can educate Americans on government and politics. They encourage us to become active participants in our democracy.

They’re not completely broken. But they need repairs, and discussing them while they happen is too late. We need a serious conversation about reform.

So let’s debate it.