America’s partisan divide is growing. Nowadays, tension within the political atmosphere has made many Americans loathe discussing politics with each other. According to a Pew Research report in October of 2017, “divisions between Republicans and Democrats on fundamental political values reached record levels during Barack Obama’s presidency. In Donald Trump’s first year as president, these gaps have grown even larger.”[1] An unexpected byproduct of this division is the rebirth of a logical fallacy known as “whataboutism.” According to the Oxford Dictionary, whataboutism is defined as “the technique of responding to an accusation or difficult question by making a counter-accusation or raising a different issue.”[2] Essentially, whataboutism means that one who is accused of wrongdoing will simply deflect and attack the accuser of being a hypocrite by comparing the current accusation to a past or current wrongdoing of the accuser. On the surface, this may seem like a cheap tactic used by politicians to try to save face when accused of wrongdoing, but the consequences of whataboutism extend beyond the dysfunction in Washington; it has stymied meaningful debate and sidelined political accountability.

American political debate has become vitriolic people fighting over political values instead of policies, and debates have devolved into senseless name-calling and conceited one-upping.[3] Whataboutism is the perfect tool for one who wants to tear down those who disagree with them by focusing the debate on the negative aspects of their opponent’s party, ideology, or character. The primary reason for the use of whataboutism is that people tend to care more about ensuring a “loss” for those they disagree with than about securing a “win” for their own side. This political vanity can make people feel joy at their political opponents’ expense. In reality, it worsens American political debate because loyalty to truth takes a backseat to personal attacks.

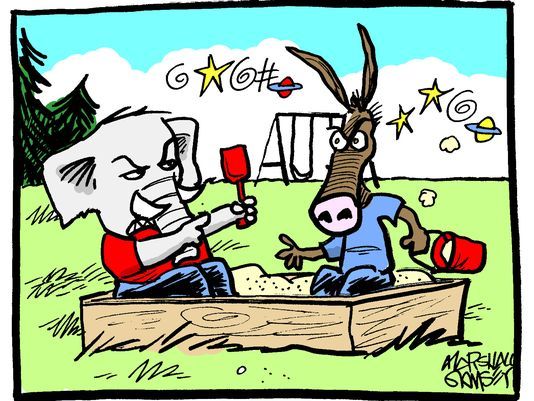

As a result, meaningful conversations about political ideology or policy do not take place within political discussions. This is incredibly detrimental to American society, as it means that voters are not exposed to the kind of facts and ideas that result in pragmatic solutions to larger problems. Instead, Americans are taught new strategies to demean their political opponents. This doesn’t result in a more educated and informed public, but rather a large elementary school playground filled with overgrown children beating their chests, trying to establish their own dominance.

A frequent controversial debate topic that nearly always employs whataboutism is terrorism. In these debates, right-wing supporters frequently cite numerous examples of ISIS or Al-Qaeda related attacks, firmly stating that Islamic terrorism should be the focus of counter-terrorism discussions. Usually this argument is linked to Islam as a whole, typically implying that religion itself is the primary factor motivating these attacks. But rather than directly argue with that claim, it’s more common for left-wing supporters to deflect and point out the right-wing hypocrisy for focusing on Islam-related attacks when there have been multiple right-wing terrorists (“but what about Dylann Roof, James Fields, or Timothy McVeigh?”). And, of course, if the debate veers into the left-wing slamming the right-wing over terrorism, the right-wing usually deflects and accuses the left-wing of hypocrisy, claiming they turn a blind eye to Islam-related attacks (“but what about radical Islamic extremism?”). Here’s the thing: Both sides have a point.[4] It can be argued that the right-wing doesn’t devote enough attention to weeding out and expelling right-wing extremists and that the left-wing’s fight against bigotry toward Muslims sometimes results in downplaying the relevance of religion as a motivation of ISIS attacks. But simply pointing out the hypocrisy of the other side prevents a real debate about how to prevent both right-wing terrorism and Islamic extremist terrorism. When the desire for superiority over political opponents is stripped away, most Americans would agree that terrorism should be prevented regardless of who commits it. But when both sides resort to accusing the other of being hypocritical, the task of coming up with solutions to tackle all forms of terrorism is sidelined.

The goal of obtaining political superiority goes further than just stifling debate; it prevents political parties and politicians from being held accountable for their actions. Since political parties are constantly trying to establish their dominance, they are less likely to admit any faults on their own side and will use whataboutism as a shield from their opponents. For example, when President Trump was accused of sexual assault by numerous women, one of the primary tactics used by him and his supporters was to deflect by raising the assault allegations made against former President Bill Clinton. Trump even brought multiple women who have levied sexual assault accusations against the former president to the second presidential debate in 2016.[5] Since Trump and his supporters heavily engaged in whataboutism to shield him, these sexual assault accusations were ignored, and there have been virtually no repercussions to the president’s standing as a political figure in American politics.[6] Since both sides are so determined to gain political superiority, they don’t want to devote any attention to dealing with the wrongdoings of their own politicians. And in order to prevent the other side from exploiting a weakness, such as a sexual assault charge, whataboutism is employed as a shield against criticisms from the other side. As a result, no one is willing to accept the flaws of their own side and no one is being held accountable for their actions. Accountability matters not only because it builds trust in political institutions, but also because it forces parties and politicians to be held to a set of common standards and to act in accordance with those standards.

While whataboutism has serious drawbacks, this isn’t to say that pointing out double standards or hypocrisy is inherently wrong. As Fred Bauer from the National Review puts it, “[Whataboutism] is a way of insisting that both sides be held to the same standards” and that penalties for wrong actions “should apply regardless of faction.”[7] The main problem with whataboutism arises when pointing out double standards becomes the only argument. Simply explaining why one side is wrong doesn’t mean the other side is right. It is possible for both sides to have flaws within their parties or ideologies, and supporters of each party should recognize this. A more measured right-wing response to the aforementioned terrorism argument could be, “While there have been terrorists with right-wing viewpoints, and these individuals are reprehensible and heinous, Islamic extremism is more relevant in today’s society given the multiplicity of ISIS and other extremist group attacks that span across the globe.” This argument acknowledges that the other side has a valid point, while simultaneously forming an independent argument that doesn’t leech off of the hypocrisy of the other side. And this form of debate is actually the solution to whataboutism. If there is debate over a controversial topic, the best course of action is for supporters on both sides to form arguments independent of perceived hypocrisy from the other side. And if there are double standards at play, point them out. This also applies to accusations; if one party is credibly accused of some wrongdoing, that party should acknowledge the guilt and then, if there is evidence of it, point out the double standards of the other party. This way, debate can return to focusing on ideas, and politicians can be held accountable for their actions. Unless both sides are willing to acknowledge that they aren’t perfect, whataboutism will flourish within American political discourse, which is a recipe for a deeply divided country and an unethical government that isn’t held accountable by its electorate.

The problem at the heart of whataboutism is the desire to tear down and anger the other side rather than engage in open-minded debate. This deep resentment toward political rivals has led to truth being sidelined and has allowed accountability to take a back seat to ego-driven contests. Both sides must learn to return to properly debating ideas with an open mind and recognize that no side is perfect. So long as whataboutism is used as a tool to facilitate division and prevent accountability, American polarization will only intensify.

[1] “The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider.” Pew Research Center. October 5, 2017. [2] “Whataboutism.” Oxford Dictionaries. [3] Justin Reedy and Christopher Wells, “Political Values Are Dividing Us Over Basic Facts, Not Just Policy Choices.” HuffPost. November 30, 2014. [4] Stav Ziv, “Right-Wing and ‘Radical Islamic’ Terror in the U.S. Are Equally Serious Threats: ADL Report (Exclusive).” Newsweek. May 20, 2017. [5] Daniella Diaz and Jeff Zeleny, “Trump appears with Bill Clinton accusers before debate.” CNN. October 10, 2016. [6] Robin Abcarian, “Will Trump ever have to answer to the women who say he harassed and assaulted them.” Los Angeles Times. November 28, 2017. [7] Fred Bauer, “‘Whataboutism’: What of It?” National Review. July 14, 2017.