“Feminist: a person who believes in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes.”[1] The ringing wisdom of acclaimed novelist, artist, and activist, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie sounded in billions of ears upon the release of Beyoncé’s hit single “Flawless***.” This excerpt from a TEDx speech turned novella was authored by one of the most prestigious and intelligent intersectional feminists of the twenty-first century: Adichie herself. However, if the clock were to be rewound just a short century, a woman of color like Adichie would have been shunned for her Nigerian descent, barred from “joining” the popular feminist movement alongside Susan B. Anthony or Carrie Chapman Catt. Given the prevalence of white supremacy during the first suffragette wave, women of color were excluded from the frontlines.[2] Sadly, this problem was not a unique one to women of color, as feminism’s roots in heteronormativity, cisnormativity, and aforementioned white supremacy left it and leave it in a precarious and problematic state—needing broad redefinition and repurposing for collective social good.

While the feminist and queer movements overall were, and are, amazing vehicles of social change for many marginalized individuals, the harboring of negative and pernicious ideals from past times has led to the continuation of a hateful faction of feminism and queer movements today. This divisiveness is exemplified in trans exclusionary radical feminism and feminists—TERFs—and anti-trans queer groups. Even though feminist movements and TERFs didn’t invent transmisogyny nor the societal power structure that harms and disenfranchises people who identify this way, even with better visibility, they, in their birth and early struggles with cohesion, did nothing to address the issues of trans and gender nonconforming individuals. Given the lack of recognition these movements have, intentionally or otherwise, they have, in fact, inflamed and aggravated the struggles of trans people today.

Following the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the immediate goal of feminism—suffrage-focused feminism—was met. The goal of the white, middle class feminists had been achieved. Women now had the legal right to vote, but the problem of the patriarchy was not washed away with President Wilson’s signature. It had just begun. By the 1950s and 60s, after World War I and World War II, women such as Betty Friedan had grown tired of the image of the white housewife and the so-called “feminine mystique;” women began yearning for more opportunities.[3] Friedan spoke for all white women when she investigated the “problem with no name” in her book, The Feminine Mystique, which many womanist leaders would later critique as an entrenched manifestation of “the white woman’s burden.”

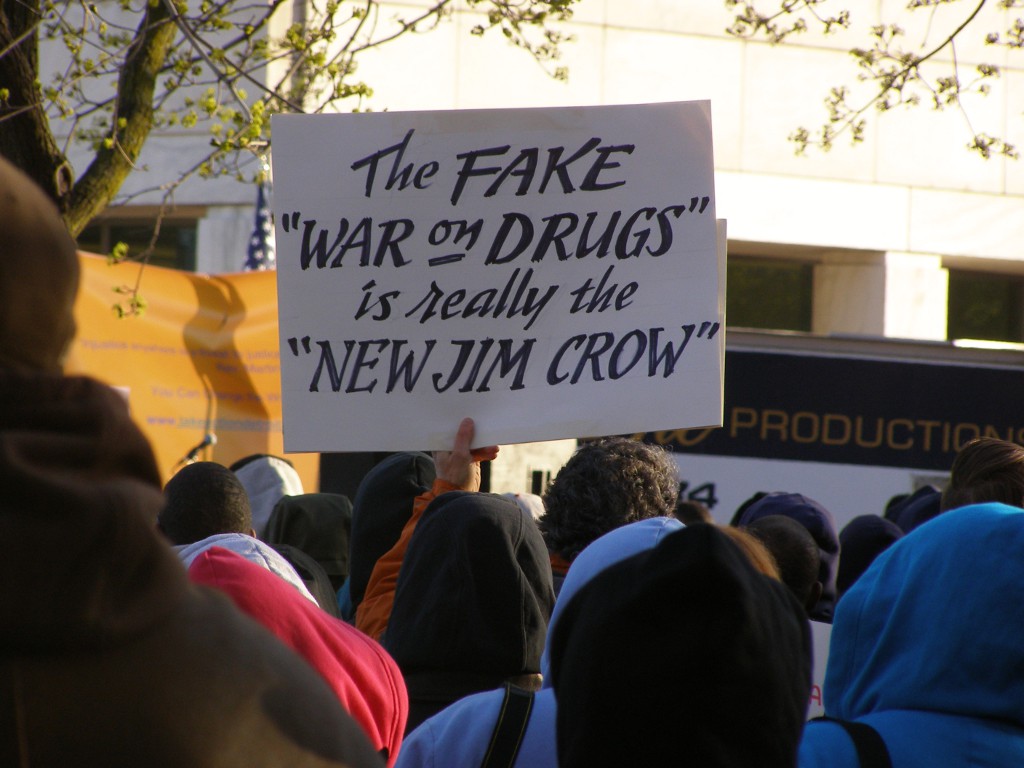

While second-wave feminism, led by women such as Friedan herself, wasn’t statically aggressive to trans individuals, it, more often than not, equated the female existence with things like menstruation and childbirth.[4] With this exclusion of trans women and women of color, many were forced to find or found their own movements, which provided feminist representation for black women, Chicano movements for Latinx and Hispanic women, and trans-friendly feminist movements for all trans, non-binary, and genderqueer individuals. As Linda Nicholson explains in her book Feminism/Postmodernism, feminism as a categorizing structure “represent[s] a set of values or dispositions,” and when existing in this vein, for her, “it becomes normative in character and, hence, exclusionary in principle.”[5] Feminism, by definition, is a tool of exclusion.[6] Even in the present, the feminist movement continues to singe arguably the most marginalized group of people: transgender (trans) individuals. Trans people not only experience discrimination from their own community and communities in terms of mockery and deliberate misgendering, but trans people are also at extreme risk of violence. Between January 2008 and September 2016, trans people were subjected to disproportionate violence, as over 1,750 trans people were reportedly murdered.[7]

Transgender people also make up the majority of suicide and homicide statistics in the United States, with 41% of respondents to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey reporting suicide attempts, compared to the 4.6% rate of average citizens, and the 21-31% rate of gay and lesbian people.[8] Suicides of girls like Leelah Alcorn, a white trans teen who took the news by storm after posting on Tumblr, are more publicized than those teens of color whose names are seemingly blurred into the concrete. Leelah stated in her suicide note that “the only way [she] will rest in peace is if one-day transgender people aren’t treated the way [she] was, they’re treated like humans, with valid feelings and human rights.” And while Leelah’s call to action was powerful and impactful for many, more still needs to be done for trans women and trans teens of color, who experience discrimination not only because of their color, but also due to their gender identity.[9] The only solution is unyielding integration.

The term intersectional feminism was coined in 1989 by American Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, who gave a name to what many non-able-bodied, non-white, non-affluent, and non-cisgender—or cis—women were already identifying with.[10] For Ava Vidal, “the view that women experience oppression in varying configurations and in varying degrees of intensity” is a given.[11] She saw that “cultural patterns of oppression [were] not only interrelated, but bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society… examples of this includ[ing] race, gender, class, ability, and ethnicity.”[12] To this day, intersectional feminist conversations strive to include all people: women and men, cis and trans people, and everything in between. Feminism should have been this way all along, but with very little visibility in the media, trans women, women of color, those with physical and/or mental disabilities, and other marginalized individuals remain unable to talk about their own experiences of oppression. Instead, there are online press conferences with Emma Watson, talks with Taylor Swift.

The problem is not with Emma Watson or Taylor Swift, who have made positive contributions to the third-wave and intersectional movements—the problem is that feminism has largely stayed a white women’s movement—not working for the “other” category in society. While amazing intersectional feminists like Beyoncé, a woman of color, have been allowed to rise to prominence in the public scene today, it is sadly the exception rather than the norm.

The most likely culprit, responsible for the current continuation and perpetuation of the trans exclusionary and largely white movement, are second wave feminists. The second wave of feminism fell from slightly before the Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s until the early twenty-first century. During this time, second wave feminist ideology and regulatory mindsets were bred in colleges, the workforce, and in the home. Lesbian feminists in the 1990s still viewed male biology, or that of perceived cisgendered men, as a “problem” and “mutation.”[13] This in and of itself still champions the biological gender binary, with men having XY sex chromosomes and women having XX sex chromosomes. Yet, in their explanation, these self-described radical lesbian feminists demonstrate a misunderstanding of biology. They theorize that all those with Y-chromosomes are mutants, building off of the false discovery that all fetuses are initially female. Carol Anne Douglas, a feminist theorist, author, and playwright, makes claims that the Y chromosome was created from radiation fusillading an X chromosome, creating the admittedly smaller chromosome. Yet, sex is determined using more than just XX and XY chromosomes; such is the case with intersex and other biologically diverse individuals, who are born with XXX, XXY, XYY, and even just X sex chromosomes.[14]

Biological inquiries become violent in the public sphere for trans people when they are largely policed and their bodies objectified. Consistently in interviews with trans women, interviewers such as Katie Couric and Piers Morgan appear so surprised at the “passability” of women like Laverne Cox and Janet Mock, saying they would’ve “never known” that the women were “born boys.”[15] The trans body is the same as any other physical body, and it is natural. As Mock, an accomplished author and trans activist states, “I… don’t marvel at it that much because there was no other choice than to be myself… I always knew that I was me; I didn’t know that it was about gender or that it was about anything other than just the inclinations I just naturally had, and the things that I was drawn to.”[16] The elements of gender are about more than being born with a penis, a vagina, both, or neither; they are about how one feels about oneself, and how they choose to express that outwardly or not. It is not the duty of another to question or police someone else’s identity, regardless of whether they disagree with it or not.[17]

However, trans representation is improving. Successful shows like Transparent (even with a cis lead actor), Orange is the New Black, and CBS’s new pilot Doubt normalize seemingly “diverse” casts, in terms of race, religion, and gender. But the process is not finished.

In 2017, trans exclusionary radical feminism is still ingrained in the feminist movements because of the overhanging ideas of second wave feminism. TERFs police physical gender and seem to want claim over the oppression of trans women face as oppression of their own, even though trans women arguably face more oppression than cis women given society’s problem with femininity. Lesbian women who appear more male are often even treated better than feminine women simply because masculinity is a societal default, as well as more acceptable—it’s better for a woman to “dress” like a man than to “become” one, like a trans man. In fact, the term “dyke,” which refers to hyper-masculine lesbian women, comes from the term hermaphrodite because they are by some believed to possess or have possessed both sex organs—as intersex people do.[18] The fact is, maleness is always treated more acceptably. It’s just worse for trans women because many wrongly believe they “choose” to become females, which is the largest injustice a designated male at birth could perpetrate—go against the patriarchal structure that would have favored them. When dust turns to dust, a woman is a woman who identifies as a woman; it is as simple as that. A man is a man who identifies as a man; period. Yet, many in our society continue to assume everyone to be cis, everyone to be straight, until proven “guilty” or “perverse.”

But the problems with feminism seem to be getting washed out by powerful and inclusive feminist movements such as intersectional and trans inclusionary feminism. Rather than vilifying the patriarchal structure of society, those that continue to not accept trans women are villainizing penises as the cause of oppression and problems in their own lives, which some trans women don’t even have; they choose to police the gender identities of people they don’t understand rather than working to understand those identities and the true minutiae of gender. Those refusing to see gender as a societal construct fail to realize that when you take away gender, nothing is inherently more important or functional; everything is just biological and existent by nature. The push-back oppression complex itself demonstrates the inherent nature of human beings, which has continued to be fostered by the patriarchal, cisgendered, heterosexual, white favorable structure of society.

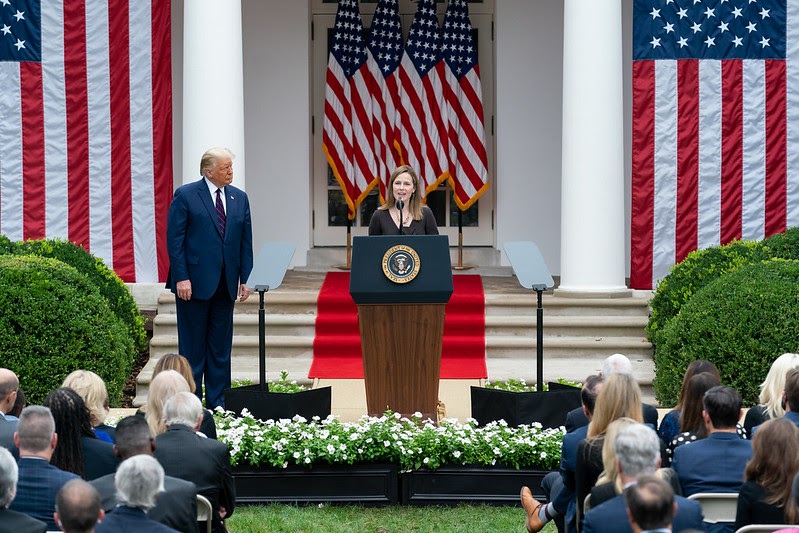

All in all, the LGBTQIAP+ communities, along with feminist communities, are working to incorporate the not at all taboo “T” into the mix. But radical feminists and stigmas among certain gay men still prove problematic in their conservation of foundational ideas from the second wave. Cissexism, the idea that all those with penises are male and all those with vaginas are female, can be just as harmful as sexism. Transmisogyny, the deliberate discrimination against trans people—women specifically—can be just as harmful as misogyny. And oppression by people of the queer community toward others in the community can be just as harmful as oppression by those outside. In-group camaraderie is more important now than ever before, as the future seems to hold not only perceptual challenges for trans and other LGBTQIAP+ individuals, but legal and policy challenges from President Donald Trump, his Vice President, Mike Pence, as well as a Republican-controlled House, Senate, and conservative Supreme Court. Mobilizing everyone around the fact that we are all important and equal in our plights for equality must be a hallmark in the journey forward for the feminist movement everywhere.

[1] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All Be Feminists (New York: Vintage Books, 2014), iBook, 35.

[2] “Suffragette’s Racial Remark Haunts College”, The New York Times, May 05, 1996, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/05/us/suffraggette-s-racial-remark-haunts-college.html.

[3] Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique, 50th Anniversary ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1963), 7.

[4] Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008), 108.

[5] Linda J. Nicolson, Feminism/Postmoderism (New York: Routledge, 1990), 365.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “TDoR 2016 Press Release,” Transgender Europe, November 9, 2016, accessed November 10, 2016, http://tgeu.org/tdor-2016-press-release/.

[8] Ann P. Hass, Ph.D, Philip L. Rodgers, Ph.D, and Jody L. Herman, Ph.D, Suicide Attempts Among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults, report, School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles, January 28, 2014, 2, accessed November 22, 2016, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/AFSP-Williams-Suicide-Report-Final.pdf.

[9] Danielle Moodie-Mills, “Commentary: The Invisible Lives of Transgender Women of Color,” NBC News, February 13, 2015, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/commentary-invisible-lives-transgender-women-color-n305306.

[10] Ava Vidal, “‘Intersectional Feminism’. What the Hell Is It? (And Why You Should Care),” The Telegraph, January 15, 2014, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10572435/Intersectional-feminism.-What-the-hell-is-it-And-why-you-should-care.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Carol Anne Douglas, Love and Politics: Radical Feminist and Lesbian Theories (San Francisco: ISM Press, 1990), 65.

[14] Neil A. Campbell and Jane B. Reece, Biology, 7th ed. (San Francisco: Pearson, Benjamin Cummings, 2005), 287.

[15] Janet Mock Joins Piers Morgan, perf. Janet Mock and Piers Morgan, CNN, February 05, 2014, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/02/05/pml-janet-mock-whole-interview.cnn.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Susan Rohwer, “So He Wears a My Little Pony Backpack? Stop ‘gender Policing’ and Let Kids Be Kids,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 2014, , accessed November 10, 2016, http://articles.latimes.com/2014/mar/27/news/la-ol-stop-gender-policing-and-let-kids-be-kids-20140327.

[18] Richard A. Spears, “On the Etymology of Dike,” The American Dialectic Society, 4th ser., 60 (1985): 318, accessed November 10, 2015, doi:10.2307/454909.