Nature abhors a vacuum. So does geopolitics. Most Americans believe that foreign aid consumes nearly a quarter of the federal budget. In reality, it has historically accounted for less than 1 percent. This widespread misconception is precisely what made it politically possible for the United States to decimate its primary development agency overnight with little public resistance.

When the Trump administration officially shuttered the US Agency for International Development (USAID) on July 1, 2025, it left behind not only thousands of canceled development projects, but a strategic void — one that China and Russia have already begun to fill through infrastructure financing, security partnerships, and political influence. Although the White House presents USAID’s dissolution as a bureaucratic adjustment, its immediate geopolitical consequences show a rapid weakening of US soft power and a widening space for authoritarian influence.

What was USAID?

President John F. Kennedy established USAID through the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act. From its inception, development assistance was framed not only as a humanitarian duty but a strategic tool of Cold War containment. In 1998, Congress made USAID an independent establishment operating within the executive branch as well as under the guidance of the Secretary of State. For over six decades, the agency played a leading role in international emergency response and long-term development. From contributing to the eradication of smallpox to supporting anti-corruption initiatives across the globe, USAID has existed as a central pillar of US soft power. Its design enabled long-term, technical, apolitical development work, and on-the-ground field missions built local knowledge and continuity unattainable through embassies alone.

Crucially, USAID’s institutional structure insulated much of its work from short-term domestic political priorities. Career civil servants, multi-year funding cycles, congressional oversight, and partnerships with local civil society allowed programs to persist across administrations and policy shifts. Although USAID ultimately served U.S. strategic interests, its development model emphasized institutional capacity-building rather than direct political alignment. This separation limited the use of aid as an overt tool of coercion or regime manipulation — distinguishing U.S. development engagement from the more centralized, executive-driven approaches employed by China and Russia.

Trump’s Wrecking Ball

The White House dismantled this framework in a rapid and unprecedented fashion. On President Trump’s first day back in office, he released an executive order demanding a funding freeze on all foreign aid obligations and launching a review of existing programs — one of the hasty cost-cutting measures under the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) — now defunct. Less than two months later, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced the cancellation of 5,200 contracts, or 83 percent of USAID programs, and stated intentions to absorb the remaining programs into the State Department. In total, over 10,000 employees were dismissed, their departures documented in widely circulated images of emptying offices across Washington.

USAID’s work was not merely humanitarian, but a strategic method of expanding diplomacy and American interests abroad. Development programs shape governance norms, protect civil society, and deepen political alignment with the United States over decades. By abruptly terminating a long-standing source of governance support, the United States left behind unmet political needs and signaled disengagement, conditions that reliably generate geopolitical vacuums and invite rival intervention.

China Moves In

China quickly capitalized on the space created by USAID’s collapse. However, Beijing’s development system is structurally different from USAID’s independent, consolidated body. Instead, China relies on a fragmented network of ministries, state-owned enterprises, and policy banks. The China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) coordinates these actors but does not command them. This makes Chinese assistance flexible, politically selective, and capable of rapid deployment where strategic opportunities emerge. China directly targets countries that hold leadership positions in key regional institutions. Countries chairing organizations like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) or the African Union experience dramatic increases in government-to-government aid, allowing China to shape agendas, deflect criticism, and strengthen its influence in the Global South.

Beijing is already attempting to move into spaces previously served by USAID, such as a de-mining project in Cambodia and NGOs in Colombia. CIDCA is also beginning to launch grassroots programs (labelled “small and beautiful,” or S&B), often in cooperation with international organizations such as the UN World Food Programme. These high-engagement local programs are exactly what will foster goodwill in the absence of American development staff. Beijing has announced its intention to scale up S&B initiatives, coordinating with its already prevalent Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) for infrastructural aid.

China’s growing role in the post-USAID environment is not simply a matter of scale, but of strategy. Beijing is filling the vacuum through targeted political aid, intensified regional diplomacy, and localized development projects, collectively repositioning China as the most dependable external partner in parts of the Global South.

Russia’s Turn

When the Kremlin celebrates a US decision, there should probably be some reevaluation. Several high-profile Russian politicians, including ex-President and Putin confidant Dmitry Medvedev, sang praises of Trump’s decision to shutter USAID. Like China, Russia is ready to seize the opportunities left behind.

Moscow lacks a large development apparatus or the financial capacity to mirror China’s infrastructure lending. Where USAID historically separated development assistance from partisan alliance, Russian engagement collapses this distinction entirely. Using political influence operations, security partnerships, media networks, and selective development assistance, Russia aims to weaken democratic institutions and expand its strategic reach.

The freeze of USAID immediately created conditions conducive to Russian expansion. Cutting off funding for civil society groups in Eastern Europe undermines pro-democracy initiatives and reinforces the Kremlin’s narrative of Western abandonment. Programs supporting independent media and anti-corruption across nations like Ukraine, Georgia, and Armenia were halted abruptly, exactly the initiatives Russia has long sought to undermine. As these sectors lost US technological assistance and funding, Russian-backed actors gained strength while local governments were left more vulnerable to political pressure.

Russia is determined to solidify the opportunity of US withdrawal permanently. The Foreign Ministry is developing legislation that would establish an official structure for an international development model based on USAID and focused on strengthening Russia’s global influence. The head of Rossotrudnichestvo (Russia’s foreign aid/cultural outreach branch), Yvgeny Primikov confirmed this move, as his department has long been under fire for operating as a cover for Russian propaganda and intelligence operations. Despite challenges to finance a robust global development operation, it is clear that Russia intends to enhance its international profile while America scales back its own.

If China fills the vacuum through infrastructure and targeted development financing, Russia does so through political absorption, expanding influence where democratic resilience has weakened without American support. The result is a creeping authoritarian advance that spreads not through capital flow, but through the erosion of transparency, civil society, and independent institutions once supported by the US.

Case Study: Serbia

In Serbia, the collapse of USAID has intensified tensions within an already fragile democracy, enabling President Aleksander Vucic and his regime to suppress civil society without guardrails and twist US withdrawal into a justification for authoritarianism. Pro-government media outlets parroted Elon Musk’s assertions that USAID was a “criminal organization” aimed at destabilizing countries and meddling in elections. When these programs were frozen and later dismantled, Serbia’s anti-corruption institutions lost not only funding but also the external legitimacy and diplomatic protection that once deterred government retaliation.

Within weeks, Serbian authorities were sent under the pretext of a criminal investigation to raid four NGOs without warrants, seizing documents and confidential personal information about their staff and finances. Three of these groups formerly received only small amounts of funding from USAID, and a third received no aid from the United States at all. Serbian authorities targeted Civic Initiatives, an organization that recently provided legal aid to detained student protestors. These attacks stem from Vucic’s growing frustrations as he attempts to quell a massive student-led movement across Serbia calling for free and fair elections, government transparency, and media freedom. The raids indicate how the absence of USAID’s institutional presence weakened the protective buffer that once shielded NGOs from overt political pressure.

The deterioration of democratic norms extends beyond civil society organizations to Serbia’s independent media. Late August 2025 marked a record high of assaults on journalists, including physical assaults during protests and harassment linked to coverage of corruption and governance issues. These attacks reflect a media environment in which journalists, already strained by resource cuts and hostile rhetoric, now face heightened risks without the safety, training, and resilience programs USAID once supported.

This increasingly hostile environment has opened space for Serbia’s historically close friend, Russia, which views Serbia as its foothold in the Balkans. An RSF investigation uncovered how Russian state media, including RT — formerly Russia Today — continues to disseminate Kremlin-aligned narratives across Serbia and the wider Western Balkans. Despite EU sanctions, Moscow continues exploiting weakened media ecosystems to amplify pro-Russian messaging and sow distrust in Western institutions. With independent outlets under pressure and a consolidated media ecosystem, these Russian narratives pervade Serbian society with little resistance.

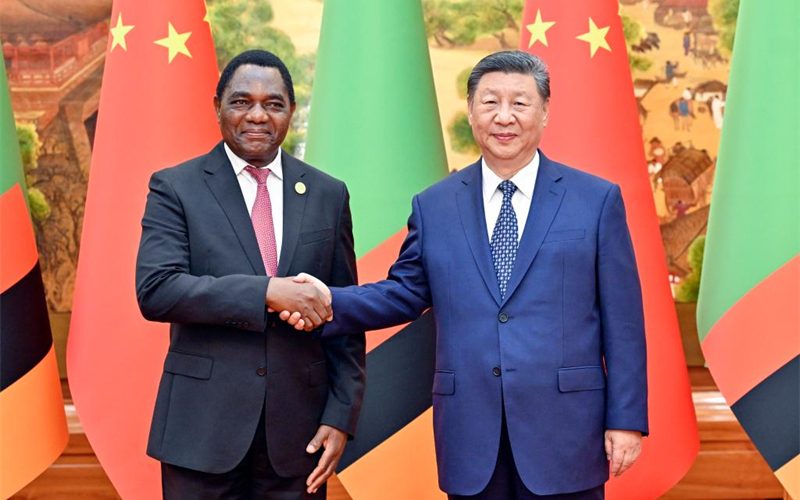

Case Study: Zambia

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the collapse of USAID has created a vacuum defined by a rapid reorganization of development projects. Zambia illustrates this shift clearly. For years, USAID operated alongside Chinese initiatives by supporting debt transparency, agricultural resilience, health systems, and governance reforms. With the abrupt US withdrawal, these institutional guardrails disappeared, leaving ministries and civil society organizations without the technical expertise, oversight mechanisms, and momentum towards self-sufficiency that they once relied on.

Through China’s BRI, Beijing has already financed Zambian railways, power plants, and highways. This approach is far from altruistic. China has been widely criticized by the international community for a lack of transparency in funding and contracts, as well as the economic and social impacts of its activities. China has also been accused of “debt-trap diplomacy,” ensnaring countries with high-interest debt that they are unable to repay, and using this as leverage to influence political outcomes and gain control over valuable mined resources.

Through confidentiality clauses, non-competitive procurement, and collateralized debt arrangements, China attempts to conceal the true extent of its involvement from the international community. A 2019 study estimated that Zambia’s loan commitments to Chinese creditors equaled approximately 43 percent of the nation’s gross national income. Without US programs supporting transparency and oversight, Zambia is increasingly susceptible to the structural risks that come with Chinese lending.

The vacuum extends beyond financial governance into the cultural sphere. USAID’s collapse eliminated exchange programs, media partnerships, and educational initiatives that once supported independent journalism, civic literacy, and local relationships. China has moved decisively into this space. Beijing has dramatically expanded its cultural diplomacy across Africa through opening Confucius Institutes, funding Mandarin-language programs, and supporting festivals and educational exchanges designed to strengthen cultural familiarity with China. These initiatives complement Beijing’s economic presence and help shape public opinion in ways that reinforce its long-term political influence.

In stark contrast to USAID, which primarily provided grants and aid, over half of BRI projects are categorized as zero-interest loans or “concessional loans.” Concessional loans are subsidized through China’s foreign aid budget to compensate for the difference between their interest rates and the commercial standard. Despite the appearance of BRI as a robust aid network, Beijing largely expects to be paid back. This framework is designed for countries initially unable to afford such projects, expanding the timeline of Chinese influence and supporting the claims of “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Zambia hosts two Confucius Institutes which face repeated criticism for unabashedly promoting Chinese state narratives and diverting attention from negative political commentary. These branches align cultural engagement with Beijing’s broader strategic objectives, including media consolidation. With US-backed media and educational programs gone, Chinese initiatives face limited counterbalances and occupy a growing share of Zambia’s informational landscape.

USAID’s withdrawal does not merely shift development leadership, but the governance environment itself. In the absence of US institutional support, China’s opaque financing structures and centralized cultural diplomacy become the path of least resistance, reshaping Zambia’s future not by overt coercion but by availability, scale, and US disengagement.

The Bottom Line

The dismantling of USAID is not simply the administrative reorganization or budget transparency initiative that the White House construes it as. Region by region, the vacuum left by the United States is accelerating the rise of authoritarianism, weakening democratic institutions, and emboldening rival powers to expand their political, economic, and cultural footprint. Looking back to JFK’s reasons for creating the program, the desecration of foreign aid as “America First” is both ironic and dangerous. China and Russia are not filling this space because their models are more effective or desirable, but because they are aggressive, coordinated, and unconstrained by the guardrails and norms that once shaped US development engagement.

The danger lies not only in the disappearance of US aid, but in the loss of a development model that checked political interference: the exact constraint absent from Chinese and Russian intervention.

If Washington continues to treat foreign aid as expendable, it risks surrendering the infrastructure of soft power that underpins global stability, democratic resilience, and American interests abroad. Rebuilding that capacity will require more than restoring budgets. It demands a recognition that development assistance is not charity but strategy, and that vacuums in global governance rarely remain empty for long. The question now is not whether other powers will fill the void left by USAID’s collapse, because they already have. It is whether the United States is willing to reclaim its role as a global leader before the consequences become irreversible.