Amidst the enduring conflict between Israel and Gaza, Iran’s proxy forces—collectively known as “The Axis of Resistance”—are hard at work in embodying Churchill’s adage to never let a good crisis go to waste. Stretching from Lebanon to Yemen and comprising scores of disparate factions including small Islamist militant groups, quasi-state actors, and designated terrorist organizations, these forces have an impressive track record for sowing international chaos. From radically restructuring the political and military landscape in Lebanon, to sparking the deadly Yemeni civil war and orchestrating terrorist attacks throughout Latin America, their global ambitions—fueled by an extraordinarily high tolerance for risk—have recently earned them front-page stories in newspapers around the world.

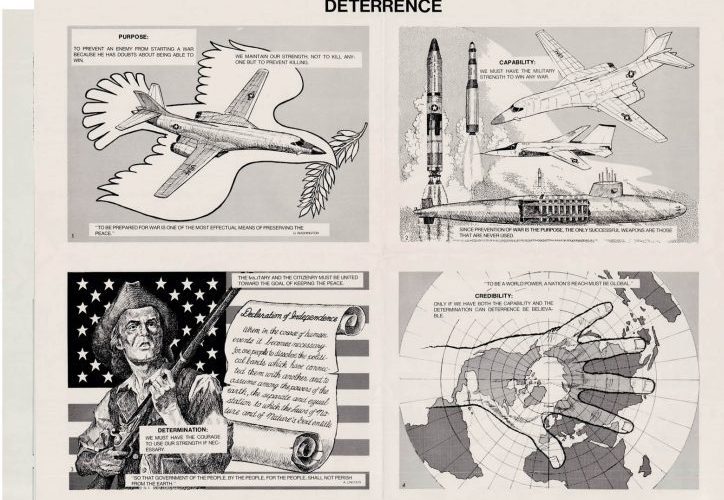

It is this quality which has now emboldened them to attack American military bases throughout the Middle East and cargo ships passing through international waters in the Red Sea. Such brazen attacks, coupled with the Biden administration’s prior reluctance to call for military strikes against these forces, have led many to call for a more assertive American response to create a deterrent. In theory, a strategy based on deterrence seeks to convince an enemy that the benefits of inaction outweigh the consequences of action. In the context of this conflict, the US military could deter Iranian proxy forces from further attacks by raising significant military costs against them. Though well-intended, these calls stem from false assumptions about the feasibility of a deterrence strategy. Refusal to strike these proxy groups is not an example of American timidity, but rather the result of a practical—albeit uncomfortable—approach.

Recent Escalations

Over the past two months, Iran’s Yemeni proxy—the Houthis—have pirated, harassed, and attacked dozens of cargo ships in the Red Sea, an area through which 12% of global trade passes. Although the Houthis use the Israeli invasion of Gaza to justify their assault on international cargo ships, the group has been indiscriminate in the ships it has targeted. While they have targeted American, French, and British navy ships, the Houthis have also assaulted ships carrying goods from Iraq to Turkey, container ships sailing from Greece to Singapore, and a Norwegian crude tanker destined for India.

The threat of these attacks, coupled with the United Nations Security Council’s condemnation of their blatant illegality, spurred the creation of a coalition led by the US and composed of almost a dozen other countries including the United Kingdom, Canada, Greece, Bahrain, the Netherlands, and Spain, whose mission is to safely escort and protect cargo ships through the Red Sea. On January 12th, the US and British navies struck over sixty targets throughout Yemen including missile launching sites, command and control modules, and radar systems resulting in five deaths.

Twelve-hundred miles away, American military bases are under attack in Iraq and Syria. From October 17th to January 9th, observers have recorded an astounding 144 distinct attacks, resulting in over sixty wounded American servicemen and the accidental death of a military contractor who went into cardiac arrest following a false missile warning alarm. In response, the US’ Central Command—tasked with defending America’s Middle Eastern and East Asian interests—has hit back against Iranian proxy forces in Iraq and Syria a total of eight times within the same time frame, resulting in the neutralization of around thirty proxy-affiliated members and multiple missile launching sites.

The unprecedented nature of these attacks—both in quantity and lethality—fuel a growing chorus calling for a more forceful American posture. The Wall Street Journal’s Editorial Board, American defense officials, and Syrian rebel commanders who regularly fight these proxy forces have voiced their disagreements with the Biden administration’s policy of excessive restraint; they contend that a refusal to impose larger military costs on the proxies carrying out these attacks only sanctions future attacks. To counter these assaults, proponents push for a new strategy based on deterrence. Deterrence is a tried and tested strategy that, when successfully enacted, is on par with a diplomatic victory. However, deterrence can only be implemented as long as Iran believes they have more to lose from a military confrontation than the US does. A look into Iran’s objectives and intentions make it clear that this is not the case.

Bending to Pressure

The current Iranian strategy can be best described as a pressure campaign, as its ultimate goal is to compel the US to increase pressure on the Israelis to end their offensive. A victory for Iran seeks to preserve Hamas’ hold over Gaza (an entity they financially, politically, and operationally support) by placing the US in a situation where supporting Israel’s military campaign means accepting the new status-quo in the Middle East: continuous proxy attacks on American bases. Before the current war between Israel and Gaza, Iranian proxies targeted American bases throughout Iraq and Syria about a dozen times in 2021, twice in 2022, and twice in March of 2023. The divergence between the low level of prior attacks and the high level levied against the US since October draws a clear connection to the ongoing war in Gaza.

Iran has for years positioned itself not only as a key funder of Hamas, the terrorist organization responsible for the October 7th attacks in Southern Israel, but also as a regional power intent on reasserting their primacy throughout the Middle East. From Iran’s point of view, Israel’s invasion of Gaza provides a unique opportunity to reshape the status-quo of American presence in the region and requires a response for domestic and international audiences. Iran will act, regardless of justification, because years of precedent created the expectation that they must.

Many who advocate for a stronger American response claim that Iran’s intention is to kill American servicemen. Yet, out of 144 individual attacks against American bases from October 17th to January 9th, precisely 0 have resulted in the death of an American service member. Either Iran’s proxy forces are incapable of killing American servicemen in their own backyard (which would negate any necessity for counterstrikes) or they are not yet interested in doing so. The closest Iran’s proxy forces came to killing an American soldier came only after the Israelis assassinated a senior general in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which was a substantial deviation from the commonly accepted rules of engagement. Regardless of whether the Israelis intended to deter further attacks, such an escalation resulted not in the concession on the part of proxy forces, but instead compelled them to intensify their attacks.

Immediately following the Israeli assassination, proxy forces in Iraq launched an assault on an American base that left a soldier in critical condition. This instance marks the closest an American soldier has come to dying due to a hostile attack since the botched evacuation of troops from Afghanistan in 2021. Because of how rare the intentional killing of an American soldier has become in the past three years, the Iranians may have used this specific attack to communicate with the US that any targeting of an IRGC senior general—whether by the US itself or Israel—crosses a red line. Prior to the assassination of its IRGC general, Iran likely did not intend to kill American soldiers (which they would have no trouble doing if it served their interests) but instead intended to coerce the US to pressure Israel into ending their military campaign.

Realizing Deterrence

Nonetheless, Iran’s determination not to kill American troops should not be confused with an unwillingness to do so. Advocates of a more forceful American posture assume that once struck by American forces, Iranian proxies would be hesitant to counter strike for fear of a larger, more powerful, American reprisal. Not only has this assumption been disproven following Iran’s response to the assassination of their IRGC general, but the Biden administration’s own statements confess that attacks against proxy positions will not deter them but are instead intended to “degrade their capabilities.” The US’ ability to deter Iranian proxies rests on the US being more willing than Iran to bear the costs of continued escalation: a reality that simply does not pan out.

The Biden administration has made it clear that their goal is not to drag the US into yet another conflict in the Middle East. Such is evident by the administration’s constant attempts to pressure Israel into scaling down the war in Gaza.

These attempts at deescalation stem from the mechanisms with which foreign policy is communicated, which is often zero-sum; there are finite limits to the number of diplomats, amount of resources, and political will of our leaders. This forces the US to prioritize, and the Biden administration holds the view that allocating aid to Ukraine—which is already at danger of nearing an end—and revitalizing the much-anticipated diplomatic and military pivot to Asia takes precedence over conflict in the Middle East. In other words, it will be exceedingly difficult for the US to convince Iran that it would bear the burdens of continued escalation.

Iran would have more to lose by acquiescing to a forceful American reprisal than they would by doubling down, both because their proxies made the first move to target American forces and because of their physical proximity to the conflict. America, conversely, would have much more to lose; both the Biden administration’s reluctance to engage in a new Middle Eastern conflict and the importance of America’s other international commitments makes it highly unlikely for the US to continue down the escalatory ladder if a tit-for-tat were to ensue.

Iran recognizes the US government’s predicament, and this awareness is precisely why they challenged the status-quo in the first place—because they know they can. One can be justifiably irritated that the American security ecosystem in the Middle East allows for the repeated targeting of American troops, but this should not cloud our judgment when thinking of ways to respond. A pragmatic approach which soberly acknowledges the current situational landscape makes it clear that deterrence is not a favorable strategy for the US to pursue against Iranian proxies at this moment. If the US were to act more assertively, the ensuing events would not indeed take the shape of a deterrent but would instead surmount to a dangerous series of escalatory responses which Iran is predisposed to win.

It would be unwise to believe that the current American response to Iranian proxy threats—that of excessive restraint—is equivalent to a neglect of duty. Instead, we must see this strategy for what it truly is: the best choice picked from a sea of bad options. Solely looking at Secretary of State Blinken’s arduous meeting record over the past months, which includes dozens of consultations and in-person visits with Arab heads of state, should be enough to demonstrate that it is not due to sheer luck that the region has thus far avoided conflict, but instead is being held together by the muscular forces of diplomacy. If this delicate balance is disrupted, it will be not because of an overemphasis on strategic restraint, nor due to a careful evaluation of a deterrent’s feasibility, but by an impulse to act for the sake of action.