“When I get confused on the train lines, I feel . . . helpless. The anxiety is always there; it’s like a shadow,” Casandra Xavier says.

Casandra is a member of the Disability Policy Consortium’s board of directors and was born visually impaired and hard of hearing. On their own, these ailments would make everyday life challenging for anyone. But years of trauma also degraded Casandra’s mental health, permanently tying her physical impairments to intense and chronic anxiety.

Nevertheless, Casandra, who is on permanent disability, does her best to push forward. She makes frequent trips from her home in the North End to Brighton to visit relatives, attend medical appointments, and work out at the gym. And for each of these trips, Casandra relies on the Green Line to get where she needs to go.

But the Green Line is hardly dependable, Casandra says. “Every time I want to use a lot of the Green Line, the announcements are not made for the stops.”

Without audible status updates, Casandra has no way to know where her train is and if it has arrived at her stop. “Because of the mix up with the trains, I would be, like, an hour late, which would then force me to get out of the train wherever I am and call an Uber or a Lyft to finish the route,” she said.

While Casandra primarily takes the Green Line for social and medical reasons, more than 65% of Green Line riders depend on the train to get to work on time. For riders with disabilities, looking to the Green Line for reliability is off the table. This inequity violates the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits government discrimination against people with disabilities, and eventually spurred the MBTA to allocate over $900 million to the Green Line Transformation: a four-stage initiative that promises to make Green Line stations and vehicles one hundred percent accessible.

The Green Line Transformation is an ambitious project that involves improving more than thirty stations and replacing every Green Line vehicle. And the MBTA has a long way to go before it reaches its destination: unrealistic goals and long construction times threaten to derail the Transformation at every turn.

Accessibility for thee is accessibility for me

“We passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, [and] the law said whenever you build something new, make sure it’s accessible,” says Peter Furth, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University. “If you’re in a wheelchair, you should be able to just roll on, roll off . . . That also provides a huge benefit to many other people . . . The accessibility improvements, it would be a mistake to think that ‘that’s not for me.’”

Besides workers with disabilities, the Green Line’s accessibility failures may also restrict educational and employment opportunities for students.

The Green Line runs directly through large universities like Boston College, Boston University, and Northeastern University—which enroll over 150,000 students—many of whom rely on the Green Line for access to the greater Boston area. Efficient travel enables students who live on-campus to commute to work and students who live off-campus to get to class.

Northeastern University in particular relies on the Green Line’s expansive reach because of its co-op work-study program—which ninety-six percent of undergraduates participate in.

Jacob Nudel, a third-year finance and financial technology major at Northeastern, needs the Green Line for his co-op at Rapid 7, a cybersecurity firm at North Station. “I hop on the D line of the Green Line and take it to North Station,” he says. “After work, the lack of sunlight makes it dangerous to bike. Ubers exist, but [they’re] pretty expensive after worktimes.”

Northeastern students who live along Huntington Avenue also need the Green Line to get to campus. The university provides these students with free CharlieCards so that they don’t need to make the twenty minute trek to campus.

“We have a whole bunch of people from the NUin program,” Alexander Young, a first-year bioengineering major at Northeastern, says. “Sometimes in the afternoon . . . it’s very packed inside the [Green Line] because that’s when a lot of people finish classes.”

The Green Line’s subpar announcement systems and the sheer number of students that ride it put students with disabilities at a disadvantage.

The Transformation

The origin of the Green Line Transformation traces back to Joanne Daniels-Finegold nearly two decades ago. Back then, Joanne—who cannot drive—found herself trapped by the very public transportation that was there to serve her.

Joanne is among the six percent of Americans with hyperhomocysteinemia. She has too much homocysteine in her blood, and with this excess comes clotting, joint pain, and increased risks of hip fracture and stroke.

Left optionless by buses’ broken wheelchair lifts, she would push herself 3.5 miles to reach the nearest Red Line station. Then, broken elevators and inaccessible train cars at later Red and Green Line stations limited where she could board and exit. Boston public transit failed her.

And she wasn’t the only one. A group of advocates across Boston, all of whom felt stranded by the MBTA, joined her and the Boston Center for Independent Living, an organization that provides services for people with disabilities, in a class-action lawsuit to hold the MBTA accountable for its failures.

In 2006, they settled and the MBTA agreed to more than 200 stipulations aimed at increasing people with disabilities’ access to Boston public transit.

Initially, the MBTA honored many of its commitments; a 2010 joint assessment between the MBTA and the Boston Center for Independent Living found that workers repaired station elevators, shortened gaps between station platforms and trains, and commissioned more accessible buses.

However, in 2013, Joanne and her team called out the Green Line as a cause for concern. While the MBTA replaced some inaccessible cars with low-floor alternates—enabling easy roll-on-roll-off access—these cars are only accessible at stations at least eight inches off the ground and, even then, require a bridge plate.

Scott Page, the Boston Carmen’s Union Green Line delegate, pointed out that there are external lifts available to patients with disabilities on low-level platforms. And while the MBTA’s assessment claimed that employees performed daily maintenance checks on lifts, riders’ experiences suggested otherwise.

By 2015, more than thirty Green Line station platforms remained inaccessible to people with disabilities. “Green Line surface stops . . . represent the area of greatest need within the rapid transit system,” wrote Laura Brelsford, assistant general manager of system-wide accessibility at the MBTA.

Three years later in 2018, the MBTA put the Green Line Transformation into action.

“From the MBTA’s point of view, [we prioritize] first safety, and then standard of care. We need to make sure that we can eliminate any [dangerous] track conditions that are out there for passengers, and that’s where you’ve seen a lot of investment over the last three years,” said Angel Peña, chief of capital transformation at the MBTA.

After improving track safety, the MBTA aims to install elevators at stations without them, raise all platform heights to at least eight inches, and replace outdated vehicles with souped-up “supercars.” “We have the type sevens, with the high floor on the inside, the type eights have the low floor on the insides, and the brand-new type nines…also have the low floor,” Page says. But the MBTA’s type ten supercars put these trains to shame. More than one hundred feet long, they can hold twice as many passengers and boast fully accessible low-floor boarding at every entrance, rather than just at the middle doors like the type eights and nines.

Finally, by consolidating close-by stations, giving trains traffic priority, and investing in better track and storage infrastructure, the MBTA looks to reduce travel times and extend the Green Line’s reach beyond Boston.

“If stations are further apart, you have to walk a little bit to get to the station, but you’re rewarded with a faster ride,” professor Furth, an expert in civil engineering, says. “A second thing that they are doing on the Green Line is transit priority . . . We can provide accessibility and speed.”

In 2020, the MBTA upgraded fifteen percent of all Green Line tracks, installed floodgates and steel doors at Fenway station, and started renewing the Lechmere Viaduct, which connects the Green Line to Cambridge. In 2022, the MBTA consolidated four inaccessible Green Line stations along the B-branch into two fully accessible ones at the Amory and Babcock stations, nearly completed the Lechmere Viaduct rehabilitation, and replaced miles of track and signals along the D-branch.

When the Transformation is complete, the MBTA promises greater accessibility for every car and station along the Green Line, shorter travel times, and simplified navigation throughout the Greater Boston area. “Our future is having an accessible, larger car that will help . . . get all of our passengers on board right away,” Peña said.

Poor plans and delayed developments

However, MBTA data reveals that the Green Line has some ways to go before it reaches its lofty aims.

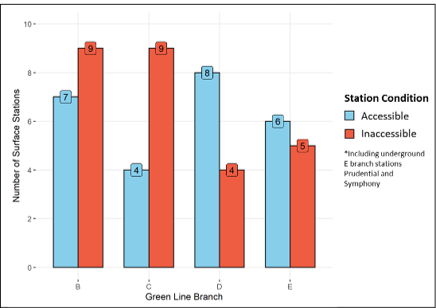

In 2015, when Laura Brelsford, the MBTA’s assistant general manager of system-wide accessibility, made specific note of Green Line surface stops as a cause for concern, thirty-one of the Green Line’s fifty-three surface stops were wheelchair inaccessible. Since the Transformation’s initiation in 2018, the MBTA has renovated or consolidated six into accessible alternatives. At this rate—about six stations every four years—it will take nearly two decades until every Green Line surface stop accommodates people with disabilities.

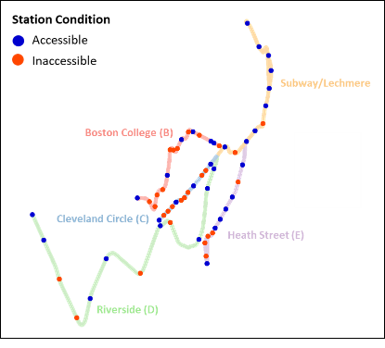

Because Green Line branches aren’t equally accessible, certain riders may have to wait far longer than others before Green Line travel becomes a realistic option. According to the Green Line’s schedules and maps website, more than half of surface stops along the B and C branches are wheelchair inaccessible.

At the same time, riders on the B and C branches report having fewer alternative modes of transportation—and a greater reliance on the Green Line—than riders on any other branch; about fifty percent of B and C-branch riders lack a car and, without the Green Line, forty percent depend on walking or ride-share services to get around, per the 2015-2017 MBTA Systemwide Passenger Survey.

Despite the urgent need to renovate B and C-branch stations, the Transformation is committing resources to the D-branch, which MBTA data shows already boasts the largest fraction of accessible stations and riders who are most likely to own at least one car. This choice means that, while the D-branch will become the first fully accessible Green Line branch, the B and C-branches will not get the attention that they need until construction on the D-branch is complete.

Tim Lasker, president of the Office and Professional Employees International Union, representing over 400 MBTA employees, attributes the MBTA’s slow progress and poor planning to inexperience. “There are a lot of people enthusiastic about what they do but that don’t have the background or experience to do it,” Lasker says. “They have a horrible track record of completing the work in a time-efficient fashion . . . Sometimes it’s setting the wrong goals, and [sometimes it’s] not being truthful about the work that’s involved.”

Besides these challenges, the Green Line Transformation takes a relatively narrow approach to improving accessibility in the first place. Even when every Green Line station has been renovated, many passengers with disabilities may not benefit at all.

For instance, the MBTA considers Haymarket a fully accessible station and the Green Line Transformation doesn’t plan on on making any improvements to it, but the station is far from perfect; Casandra, who is visually and auditorily impaired, says that, “at Haymarket, me and my mobility instructor, we both couldn’t hear the speaker clearly, it was muffled.” Without clear announcements, Casandra had no way to tell if an incoming train was traveling inbound or outbound.

Among Green Line stations next on the Transformation’s agenda—Eliot, Waban, Chestnut Hill, Beaconsfield (D-branch), and Symphony (E-branch)—the MBTA intends to improve lighting fixtures and signage but not station speaker systems.

Aliska Gibbins, a professor of mathematics at Northeastern University, stopped using the Green Line altogether once she became dependent on a wheelchair for mobility. While the stations that she frequented are officially wheelchair accessible, lackluster employee support makes riding the Green Line tedious and embarrassing.

“The Red Line and the Orange Line, they have workers around . . . [but] the Green Line, no one was really there to tell me what was available. The only time I would find out what to do is if I talk to a driver, but then I’m holding up everyone on the train,” she says.

Instead, Gibbins relies on the MBTA’s RIDE program: a door-to-door ride-sharing service for people with disabilities. “You have to book, by six o’clock the night before, you tell them when you want to get to your location and when you’re ready to leave,” she says. Then, “a worker will take a van or a sedan… [and] drive me.”

Data, experts, and experiences paint a pessimistic picture of the Transformation: it is progressing slowly, it was poorly planned, and, from the outset, its goals were never going to address the diverse needs of its ridership. But they also suggest ways to turn things around.

For instance, Lasker says that hiring more experienced workers and improving contract management are two ways to speed up planning and construction. “Their contract management is horrific . . . the financial people and the legal people, [they] don’t hold the contractors’ feet to the fire,” he says. “The whole hold up with the Green Line extension: they were [proposing] like multi-multi-multi-million-dollar stations. What were they thinking?”

Two more ways, Casandra says, are to ensure that stop announcements are clear on all trains and stations and to improve disability awareness training.

The Green Line Transformation is an ambitious project. Renovating over thirty stations, replacing thousands of feet of track, and upgrading the entire fleet of Green Line vehicles is no easy feat. And the MBTA’s decision to pursue these goals demonstrates a real commitment to improving accessibility, Lasker says. But so far, he critiques, the Transformation has suffered from the same setbacks as other MBTA projects: overly optimistic goals, poor planning, and slow construction.

“Accessibility . . . is something that I have to praise the T for because they have a very good [Americans’ with Disabilities Act] department. They have spent literally millions and millions of dollars on working on accessibility,” he says. But, “they [only] tend to manage by putting out fires.”