Though it is a significant political and economic union that prides itself on democratic state cooperation, the European Union sees astounding quantities of tax evasion across its member states. While its international reputation evokes welfare for the poor, national healthcare systems, and free college education, these public goods face the danger of disintegration as EU corporate tax policies remain weak in addressing massive tax avoidance across the region.

Tax evasion is a global phenomenon: around 8 percent of the world’s total wealth is held in tax havens. In Europe, Switzerland is dominant in hidden wealth management, attracting new business globally with an emphasis on customer secrecy. A 2015 study shows Switzerland houses approximately $2.3 trillion of foreign wealth.

In the global south, this fraction is often much higher, with Africa’s offshore wealth nearing 30 percent. For regions with consistent conflict and inequality, such as Russia, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, the fraction of hidden wealth approaches a whopping 50 percent, money that could help with maternal death during labor, infant mortality, or public education. Many of these offshore wealth operations are closely connected with EU member states, Switzerland, and European overseas territories. The EU’s failure to combat corporate tax evasion creates massive public wealth losses in the world’s most impoverished communities. The EU should leverage its economic power and close alliance with the United States to initiate global action to hold multinational corporations accountable.

Tax Fraud 101

In 2007, Starbucks’s United Kingdom accounts showed their tenth consecutive annual loss, despite the company being the second-largest restaurant or cafe chain globally. UK tax accounts show that since Starbucks opened in the UK in 1998, the company has profited over £3 billion ($4.8 billion) in coffee sales, opened 735 outlets, but paid only £8.6 million in income taxes, well below the expected quantity of profit tax. That same November, former Chief Operating Officer Martin Coles told analysts that the UK unit’s profit was the main source of capital funding Starbucks’s expansion in other overseas markets.

The UK caught Starbucks red-handed in a massive international tax avoidance scheme. Its major methods boil down to inflating costs and transferring profits to shell companies. First, Starbucks records 6 percent of its sales profits as “royalties” for the use of its own brand and business model. Then, it transfers the profit to the Netherlands and Switzerland, where earnings from royalties are taxed at rates as low as 2 percent. On top of this, Starbucks inflated its recorded expenses such as staff, roast processing, and coffee bean purchases, relative to the average market prices. It also shifted profit from one balance sheet to another via intercompany loans, finally placing it in tax havens or offshore hidden accounts. Upon UK tax authorities’ investigation, Starbucks’s spokesperson and auditors have all declined the accusations and refused to comment further.

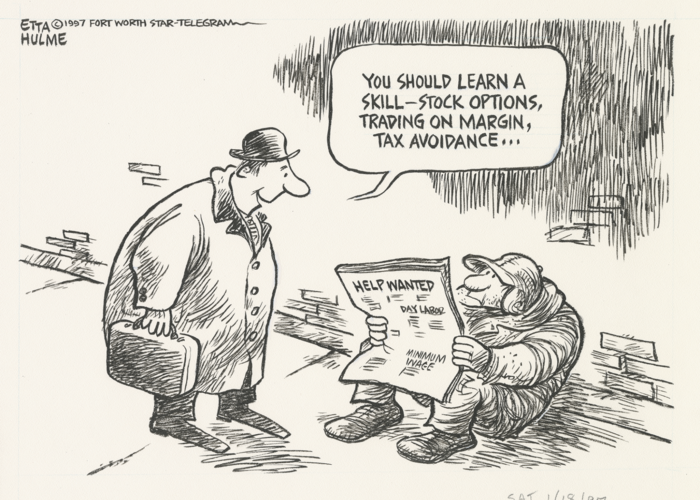

The European Union is riddled with companies like Starbucks, doing the best that they can to extract money that should fund public goods and repurpose it for their own gain.

Key Drawbacks and Mistakes

In the EU, member states retain the power to decide their own national tax rates. The incentive to attract more business and financial activity creates competition for low tax rates and other forms of corporate benefits. However, national actions against tax fraud are ineffective, allowing corporations to exploit this independent-tax-code model.

The Hidden Wealth of Nations by Gabriel Zucman explores the history of tax havens and regulatory efforts to combat wealth loss.

When France passed an anti-fraud law, French wealth quickly poured out to foreign banks who happily took depositors’ money and kept them anonymous. A century later, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) instituted on-demand exchange of information, which mandated that countries release client information when concrete evidence of illicit acts are presented. However, the OECD initiative proved to be ineffective. In reality, concrete evidence is often found through thorough investigation of foreign accounts, so this strategy was insufficient in stopping tax avoidance.

With all of these lessons taken to heart, the EU initiated the European Union Savings Directive in 2005, which required every member state to cross-inform national tax authorities of foreign client account details.

Due to the EU’s strict democratic system, major decisions can only be made on the basis of unanimity. This made authoritative enforcement of the directive virtually impossible as tax haven states inevitably deadlocked negotiations. In the end, lobbyists watered down this EU-wide policy to negligence. The directive granted tax haven countries such as Luxembourg and Austria favorable terms and the directive did not apply to non-EU member states who are heavily involved in the European tax fraud process, such as Switzerland and Singapore.

The directive gave Luxembourg and Austria the choice to either identify foreign citizens’ accurate income streams or make foreign citizens pay a tax to remain anonymous, called the “withhold tax.” In 2011, the EU raised the withhold tax from 15 percent to 35 percent.

On the surface, providing a withhold tax option seemed to be the perfect compromise. Offshore banks could maintain customer secrecy while tax authorities received their lost national revenue. And, the tax only affected households unwilling to report their off-shore interest income—tax evaders—while leaving compliant households unaffected. Most significantly, the directive only applied to accounts held by individuals, not organizations. Assuming tax evaders would like to spend this money eventually, no matter how many shell companies, hedge funds, or intercompany loans the money flows through in disguise, it would eventually arrive as personal income in a privately-held checking account. Therefore, the design left general international trade unharmed while targeting money laundering by high corporate officials.

In reality, due to differing tax rates across countries and the fact that the withhold tax was flat—it applied equally to different levels of wealth—the new directive created confusing and disproportionate reward-punishment incentives. In some cases, tax evaders paid less withhold tax than they would have legally paid through the normal taxation process, rendering the tax negligible. Moreover, the directive violated EU countries’ fiscal sovereignty by stripping their right to choose appropriate tax rates. It also only applied to wealth-generated interests, not dividends and other forms of investment revenue. This made shell companies, trusts, and hedge funds the obvious substitute for tax evasion.

Lessons Learned

Tax haven countries have no interest to cooperate with the rest of the world in disclosing their client information. And their clients, often rich and powerful, may aggressively lobby to prevent such changes. Therefore, the EU should implement a powerful enforcement mechanism to secure compliance. This could be in the forms of high economic sanctions, country-specific tariffs, or other mechanisms that compensate victim nations for the cost that tax havens impose on global public goods. Further, since multinational corporations transfer profit across borders as a core strategy to evade tax, companies should be taxed by their global profit. This could readily decrease the effect of profit manipulation, and combined with a global information registry it would ensure that there is no hidden vault for evaded wealth.

Current Developments

Thankfully, in 2021, the OECD initiated a new global tax regulation named the two-pillar solution. This new directive aims to ensure a fairer distribution of taxing rights among jurisdictions over the largest and most profitable multinational corporations, and put a floor on tax competition by creating a global 15 percent minimum effective corporate tax rate.

Pillar One targets multinational corporations who exceed €20 billion in revenues and have profitability exceeding 10 percent. It intends to reallocate parts of their profit to the countries where the sales and services occurred.

Under Pillar Two, a much wider group of multinational corporations—those with over €750 million of annual revenue—would be subject to a global minimum corporate tax. Now, even if the jurisdiction has lower tax rates than the global minimum, those profits would still be taxed at 15 percent. In October 2021, 137 countries agreed to impose this new directive, paving the way for the most significant overhaul of international tax rules in a century. The EU reached unanimity in December 2022 after cutting off EU funds to Hungary and Poland, who eventually dropped their objections.

The OECD estimates the minimum tax could boost government revenues by $200 billion annually. The reform would likely lessen international tax competition, clarify national tax revenue, reduce convoluted maneuvers in the international tax system, and help increase global GDP by up to 1 percent annually.

The OECD needs strong political backings from both the EU and the US to push the directive to the rest of the world. Unfortunately, despite the Biden administration’s best efforts, the legislation faced massive GOP rejection and died on the congressional floor. As a host and major beneficiary of many multinational corporations, it is time for the US to shoulder its responsibilities and stop US-based multinational corporations from exploiting vulnerable communities. Not only would this directive boost government revenue domestically, its contribution to foreign economies would facilitate more economic activity and lift global standards of living, a goal the US has touted for years.

Following the breakthrough would be years of efforts to incorporate these rules into national law. While many legislatures have agreed to the “big ideas” of such policy, there’s no consensus on the specifics of executing these pillars. Nonetheless, the U.S. government must acknowledge its keen responsibility to bring momentum behind this long-overdue resolution against corporate tax evasion.