The Texas Heartbeat Act, or Senate Bill 8 (SB8), came into effect on September 1, 2021. The bill—perhaps one of the most uncompromising legislative measures to regulate abortions since the Supreme Court’s ruling of Roe v. Wade—bans almost all abortions in Texas after six weeks of pregnancy, including those that are a result of sexual abuse or incest. The bill is the first of its kind to bestow enforcement abilities on private citizens through civil lawsuits.

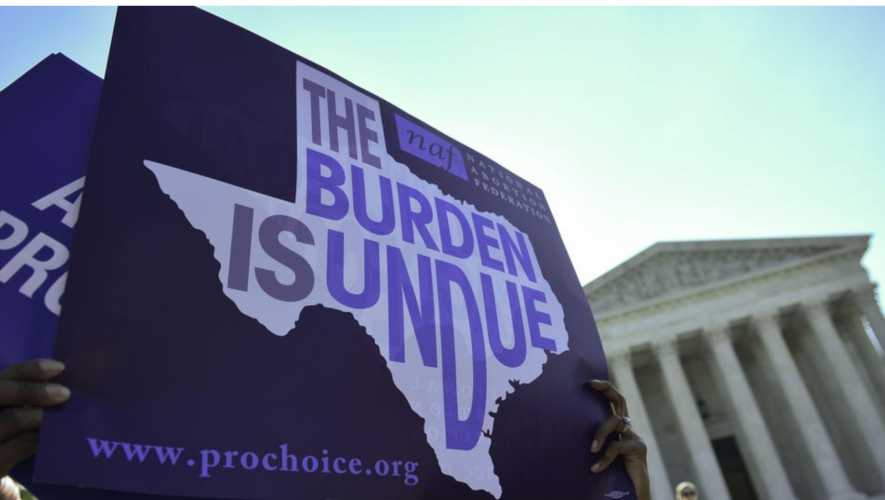

When SB8 came into effect, Planned Parenthood and other pro-choice advocates and media outlets immediately condemned it as unconstitutional. Critics pointed to how the bill ignored judicial precedents established for individual rights—impeding privacy and abortion rights.

However, SB8’s ambiguity shields the policy. Should the bill ever be challenged in court, the plaintiffs would struggle to name a proper defendant in the case because the bill gives enforcement authority to private citizens. As such, legal challenges could bring several administrative issues to the fore.

When comparing the relevant provisions of SB8 with landmark Supreme Court decisions—both in text and context—the bill’s negligence towards abortion rights and Supreme Court holdings and precedents is self-evident.

Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey

Before the landmark Roe decision, Texas considered abortion a criminal offense. Articles 1191 to 1194 and 1196 of the 1961 Texas Penal Code set forth a two to five-year incarceration period for anyone attempting to obtain an abortion in addition to a $100-1000 fine. In 1970, attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington challenged Texas’s laws in the Northern District Court on behalf of Norma McCorvey (better known as Roe).

After the lower courts heard the case, Judge Golberg and two other judges from the District Court declared the Texas code unconstitutional, making abortions a fundamental right. The Judges considered the Texas code unconstitutional because it violated the plaintiff’s unenumerated rights. The Ninth Amendment protects such rights and declares that they are “retained by the people.” Furthermore, the Judges concluded that the code also violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The provision guarantees and reaffirms fundamental rights to all Americans. The Roe ruling was a milestone, laying the groundwork for abortion protection at the federal level. However, the lower courts declined to grant an injunction, allowing the Texas law to remain. Later, the State appealed the decision and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The Court heard Roe in December 1971 and again in 1972. In 1973, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, deemed Texas’ abortion penalties unconstitutional. Justice Hugo Black argued that the Constitution does not explicitly mention the right to privacy, but that the Court found roots of the right to privacy in the Bill of Rights. Furthermore, Justice Harry Blackmun—author of Roe’s majority opinion—argued that fifty years of judicial interpretation of the Due Process Clause upheld the right to privacy.

The right to privacy extended into activities such as marriage, procreation, contraception, and familial relationships. As such, the Court declared that there was precedent defining privacy under the Fourteenth Amendment and it was “broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.”

Though Roe is perhaps more well-known and identifiable, current precedent governing American abortion laws do not reflect all of the case’s provisions. Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) partially overruled Roe. Writing the plurality opinion for the Court, Justices David Souter, Anthony Kennedy, and Sandra Day O’Connor maintained that they would uphold the three fundamental tenets, or “essential holdings” of Roe: first, women have a right to abortion before fetal viability; second, states can restrict abortions after viability; last, states have an interest in protecting the lives of women and their children. The Court defied all expectations of overturning Roe, as most of the Justices held anti-abortion sentiment. Souter, Kennedy, and O’Connor asserted the importance of institutional integrity and stare decisis (respect for precedent previously established by the Court) as the governing attributes in upholding the essential aspects of Roe.

However, Casey overturned Roe’s trimester framework, which prohibited states from applying regulation on abortions during the first trimester, but allowed limited regulation in the second and total in the third. Casey adopted the viability analysis due to the significant advancements in medical technology. The Justices cited studies that proved that fetuses could be viable at week twenty-three or twenty-four of pregnancy, earlier than the twenty-eight-week mark.

By replacing the trimester framework, the plurality opinion replaced Roe’s strict scrutiny analysis with an “undue burden” standard, which applied when assessing the legality of a state’s abortion regulation. O’Connor first introduced the “undue burden” standard in her dissenting opinion in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health. She proclaimed that state regulations could not place substantial obstacles on abortions. However, she added that the state had the right to regulate abortions should there be a legitimate purpose to do so. As such, Casey broadened the state’s authority to limit abortions.

Certain legal opinions have questioned Casey’s “undue burden” test. Mary Ziegler, a law professor at Florida State University, claims the standard is ambiguous and difficult to apply, as certain historic laws have made it hard to receive abortions, and used the guise of the states’ interest to justify harsh regulations. Blackmun also criticized the “undue burden” standard, describing it as “manipulable” in his Casey opinion.

The ambiguity surrounding what regulations constituted an “undue burden” arguably empowered states to test the extent to which they could limit abortion accessibility. For example, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 2 (HB2) in 2013, which added strict and expansive requirements and restrictions on abortion clinics. The law stated that clinics unable to comply with the updated standards would have to close, leading to the closure of twenty-three of the state’s forty-two clinics. The Supreme Court eventually struck down the law, noting that HB2 did not intend to protect women’s health. Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority opinion highlighted what legal scholars feared: the lack of clarity surrounding the “undue burden” test would allow states to adopt opportune regulations that eliminate abortion access.

The Texas Heartbeat Act

SB8 requires all physicians who plan to perform an abortion first to determine the presence of “cardiac activity” in an unborn child. Should physicians find the fetal heartbeat of an unborn child, they cannot “perform or induce an abortion.” The provision of the legislation allows for any private persons residing in Texas to sue someone for performing or assisting the process. The list of potential defendants extends to counselors, lawyers, financers, and those who provide transport to the clinic, including taxi drivers or ride-sharing companies. The bill is explicitly “pro-life,” as reflected in the language of the provisions. For example, the bill refers to a fetus or embryo as an “unborn child.”

SB8 is exceedingly detrimental to reproductive rights in Texas. The law criminalizes abortion as early as six weeks into a pregnancy; most women only find out that they are pregnant after six weeks. Consequently, 85 percent of Texas abortions occur after this mark. According to Casey and Hellerstedt, SB8 creates an undue burden on abortion access, violating the Fourteenth Amendment.

“Undue burden” arises because the law charges those facilitating abortions with harsh fines and potential incarceration. These penalties will cause some to pause services that support abortions, such as taxi drivers refusing to drive patients to abortion clinics. Furthermore, the six-week restriction could deny abortions to women before they know they’re pregnant and is an explicit undue burden. In fact, reports surfaced immediately after the bill passed that many abortion clinics, including Planned Parenthood and Whole Woman’s Health, halted operations.

Upon SB8’s passing, many pro-abortion institutions filed an emergency application to the Supreme Court, seeking an injunction. The Supreme Court voted 5-4 against providing an injunction because of the plaintiffs’ inability to name a defendant. Justice Sonia Sotomayor accused the Court majority of ignoring fifty years of precedent that should strike down the law. She called the opinion “stunning” and criticized the majority for having their “heads [buried] in the sand.”

Sotomayor also highlighted that the law insulates the state “from responsibility for implementing or enforcing regulatory regime.” Many legal scholars argue that SB8 intentionally shields the state from review or subsequent injunction. Firstly, states benefit from the concept of “sovereign immunity,” which protects them from getting sued directly by a plaintiff attempting to block a state law. Additionally, any plaintiffs in the case of SB8 cannot follow the typical path for legally challenging legislation. Because of sovereign immunity, citizens normally sue state officials acting on behalf of the state to acquire an injunction.

Despite the Court’s refusal to hear the case, it did not rule out a future hearing. As such, SB8 remains active in Texas. Simultaneous to SB8, the Texas Legislature passed the Human Life Protection Act (HB1280). The bill prospectively bans all abortions with no exceptions should the Supreme Court overturn Casey.

In December, the Supreme Court heard Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which challenges restrictions on state regulation of pre-viability elective abortions. The case assesses the constitutionality of Mississippi’s law, which bans abortions after fifteen weeks, much before viability.

However, the Supreme Court can redefine current jurisprudence surrounding the Fourteenth Amendment by overturning its ruling in Casey. It may attempt to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause doesn’t protect the right to privacy because the Constitution does not explicitly mention the right. Considering the differences in jurisprudence on the Court—which mostly consists of justices who criticize Roe’s constitutionality—it is likely that the Dobbs’s decision overturns current precedent and establishes new, more limited ones.

If the Court holds that pre-viability regulations are constitutional, Texas’s SB8 and HB1280 will likely stand. These developments should concern pro-choice supporters and activists throughout the country.