Are We Ready for Future Pandemics?

In a speech on the eve of the Paris Agreement in 2015, then-US President Barack Obama recognized the need for a better international cooperation structure for possible pandemic control and prevention. He warned that there may be a time “in which we have an airborne disease that is deadly, and in order for us to deal with that effectively we have to put in place an infrastructure not just here, [the US], but globally that allows us to see it quickly, isolate it quickly, [and] respond to it quickly.”

Six years later, Obama’s premonition came true, as humanity deals with COVID-19, one of the most global and deadly pandemics in history.

The current international institutional structure has been insufficient in combatting all the challenges that this pandemic brings. However, it is not the UN, the World Health Organization (WHO), the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, or the bureaucratic aspects of these organizations that have failed, but the lack of strong global leadership and the absence of a common written framework to facilitate international coordination within and across these organizations. More compromises by global actors, as well as a reformed global public health cooperation model, must be set in place.

The Dangerous Lack of International Leadership

With COVID-19 vaccinations increasing worldwide, international cooperation has aimed to address problems in global public health, but these efforts have not been as effective as possible due to a lack of distinct leadership. For instance, the retreat of US leadership during the Trump administration pushed China to be more present in international organizations and attempt to fill the gap that the US purposely left due to its nationalist approach.

This lack of international leadership is unprecedented in the post-World War II world, as the US had led the global institutionalist movement until today.

The Trump administration showed a minimal commitment to international cooperation on public health, making mistakes ranging from public disagreement with other major actors—like China or the European Union—to withdrawing from the WHO. The latter would have left the US and the rest of the world in a worse position to tackle COVID-19.

That said, no other state actor has been able to fill in that gap. Only China shyly attempted to do so at the beginning of the pandemic with its so-called mask diplomacy, pledging medical supplies and resources to countries as a form of international aid. The leadership gap is still apparent today, as the United States and the EU are getting their citizens vaccinated faster than developing countries, such as Brazil or India, struggling to immunize their populations. The so-called Global South is not receiving the necessary assistance from the Global North, which sees itself throwing vaccines away while there is scarcity in other countries.

While facing COVID-19 as a major global challenge, the international community has shown that the way it is structured today does not provide an effective global governance model. However, as has happened in the past, crises provide opportunities for creativity and reform. For change to happen at a global level rather than at disparate national levels, international leaders must take action to tackle a pandemic that seems likely to stay with us for longer than we expected.

The Lack of International Infrastructure: An International Public Health Treaty?

The second reason for incoherent responses to public health crises is the inadequate functioning of existing institutions. This inadequate infrastructure translates not directly to the institutions themselves, but the lack of international cooperation by member states within and outside their frameworks. Member states must outline clearer actions in the shape of an international treaty to address this problem, as has been done for issues like climate change.

Currently, there is no international treaty that makes states follow common guidelines when facing pandemics. There are, however, legal bodies like the International Health Regulations (IHR) of 2005, which tries to make all states collaborate when global health crises emerge. The purpose of the IHR (2005) is “provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”

The COVID-19 pandemic ignored this purpose, as trade and travel routes stopped even within the borders of the EU and its Schengen partners. However, the IHR does set an important base for international cooperation that could be again effective when new leadership comes to the EU member states. Through international cooperation, this supranational organization responds to alleged trade and health rules violations during international public health events.

There are also already multilateral mechanisms in place that could battle these public health challenges or serve as the place to create an international treaty. Institutions such as the WHO, public-private partnerships such as GAVI (which increases access to immunization in poor countries), and other international mechanisms have helped mitigate some effects of the pandemic. These organisms address health at a local, national, and international level, but they lack guidelines that could delineate a cooperative framework.

As the UN specialized agency that focuses on international public health, the WHO should establish an international health treaty. The WHO already has past successes in efficiently targeting public health crises, such as its efforts against smallpox, eradicated in 1980 after the WHO launched an intensified plan in 1967. That collective effort showed that these agencies are effective if the leadership is in place; the infrastructure just has to be strengthened.

Summarized Solutions

COVID-19 highlights the risks of diseases that race across borders and the need for effective national and global responses. The answer lies in international cooperation, as national and regional institutions were overwhelmed during the major waves of the pandemic, as India demonstrates today. That is why we must learn, as one planet, that cooperation is possible, even though the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed even the firmest institutionalists to lose faith. We need to believe more than ever in the concept of good global governance.

If anything, this pandemic has shown that international leadership and a higher degree of cooperation at the public and private levels are musts to overcome challenges in the realm of global public health.

On that note, we cannot rely anymore on the leadership of superpower states alone but must look to international and regional organizations. The EU exemplifies this, through both the COVID-19 pandemic and in other areas such as international environmental policy. Following larger groups of states, such as this supranational organization, could help us combat the lack of leadership that arises when individual states pursue nationalist ends.

Secondly, today is the time to create international partnerships between the public and the private sectors, like the COVAX initiative. For that, the UN or WHO must develop an international treaty to regulate pandemic action and cooperation that includes the private sector, as they can become the most important donors when facing these challenges.

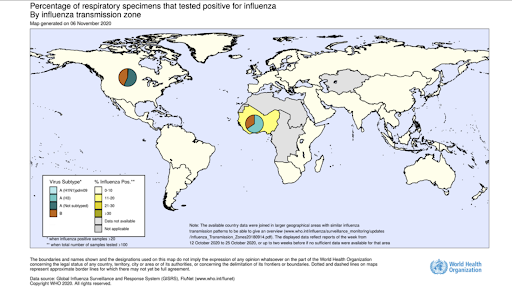

A third pillar to consider is a system that encourages information sharing and monitoring. In the current pandemic, China shared the genome of the coronavirus in January 2020. It is time to expand scientific information sharing. Proper regulations based on international cooperation could address new pandemics and international public health crises.

In sum, we might not look at the global pandemic response yet with an optimistic view, but we can consider this challenge as a door-opener for new forms of cooperation. As Bill Gates pointed out during the 2010 swine-flu epidemic, these crises serve “as a wakeup call to get us to invest in better capabilities because more epidemics will come in the decades ahead and there is no guarantee we will be lucky next time.” But, this is not a matter of luck; there were human factors that prevented us from targeting COVID-19 with a more homogenous response. The international community must learn that this can be a pivotal point that could provide a new opportunity to modernize and adapt our current international system to tackle other common challenges.