We have to look past the circling buzzards.

After Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in September, many observers lamented the Republican leadership’s rank hypocrisy in immediately filling her seat despite stonewalling Merrick Garland four years earlier.

But the critical problem wasn’t the GOP’s disregard for the rule they’d concocted. It was their normalized use of ridiculous rules of engagement.

Amy Coney Barrett was nominated by a president who lost the popular vote by almost three million votes, then confirmed by a Senate majority representing 13.5 million fewer people than the minority. Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh, all installed under these circumstances, are empowered to interpret the Constitution for life.

These appointments happened because the mechanisms that translate our votes into representation do not work. And it’s not just the presidency and the Senate. From who gets to vote to how they’re grouped to how the votes are tallied, the mechanisms are broken. Some snapped under the pressure of demographic shifts, others were dismantled recently and intentionally.

The point is not necessarily that these flaws benefit Republicans, although they do. It’s that in order to translate the public’s will into policy, democratic institutions must represent the public. Ours don’t. And as far as national policy goes, none of us will be fairly represented until all of us are.

You don’t pick politicians. They pick you.

To ensure proper democratic representation, people must choose their representatives. It’s axiomatic, and yet we can’t get it right.

Washington, DC, residents can’t vote for the congresspeople who control their budget. US citizens in Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the US Virgin Islands also lack voting representation in Congress, and cannot vote for a president empowered to send them to war. Some Supreme Court justices defended these undemocratic precedents because the “alien races” were not ready for Anglo-Saxon democracy.

The federal government ought to honor each jurisdiction’s preferred path to equal representation, be it statehood, amended special status, or some other solution. Only through full voting rights can they pressure the rest of the country to stop treating them as second-class citizens.

Residents of states have full voting rights on paper, but not always in practice. For instance, every state except Maine and Vermont strips the voting rights of felons. Seventeen states restrict voting for felons in prison, twenty require them to clear parole or probation, and the rest strip the right temporarily or indefinitely even after a person clears both. These laws disenfranchise roughly five million Americans, nearly half of whom reside in states that penalize people after they complete their sentence. Black people, who are disproportionately victimized by mass incarceration, have lost the right to vote at nearly four times the rate of non-Black people.

Felon disenfranchisement is easy to accommodate because the felons are tucked out of sight, first physically, then socially. That doesn’t make it logical, ethical, or acceptable, nor does it scrub the reality that disenfranchisement deliberately deprives Black people of influence. An inalienable, meaningful right to vote is one that cannot be lost, even after a conviction.

Not that it’s the only way politicians manipulate whose vote counts. For decades, Republican officials have deployed voter fraud as a smokescreen for all kinds of voter suppression, and President Trump epitomized this. For one, they want to require voters to present a photo ID.

It’s a solution without a problem. Voter ID laws supposedly combat voter impersonation fraud—a person pretending to be someone else to vote unlawfully. Unsurprisingly, this is rarer than being struck by lightning; after all, who would risk prison time to cast a few extra votes? Even the conservative Heritage Foundation, which falsely claims voter fraud is a serious problem, can list no more than thirteen impersonation cases over the last four decades, a minuscule fraction of ballots cast.

Voter fraud is a pretense to require the sort of ID that poor, older, and non-White voters find it tougher to obtain. These laws seem race-neutral, but the outcomes are not, and Republican legislators know that. In 2016, a few months before racially biased voting laws boosted Trump and GOP candidates nationally, a federal court invalidated a North Carolina law for targeting Black voters “with almost surgical precision.”

But the Supreme Court has not been so kind. For decades, the Voting Rights Act compelled jurisdictions with histories of voting discrimination to pass federal scrutiny when they changed their voting laws. The Court gutted this mechanism in 2013, contending that preclearance had worked in halting voter suppression and was thus outdated. Doing so, as Justice Ginsburg pointed out, was “like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you aren’t getting wet.”

By rejecting reasonable proactive restrictions and leaving citizens to sue after the unjust elections happen, the Court ushered in a wave of discriminatory voter ID laws. Laws making registration and voting easier were scrapped. An estimated two million people lost their voting status.

And all of this is to say nothing of strategic voter roll purges, the moving of voting sites, and the limiting of voting times, which make it harder for people, especially people of color, to cast ballots. Especially in the South, commonplace and racist voter suppression perpetuates generational disenfranchisement, a reminder that American democracy has always been defined just as much by who it has excluded as who it has included.

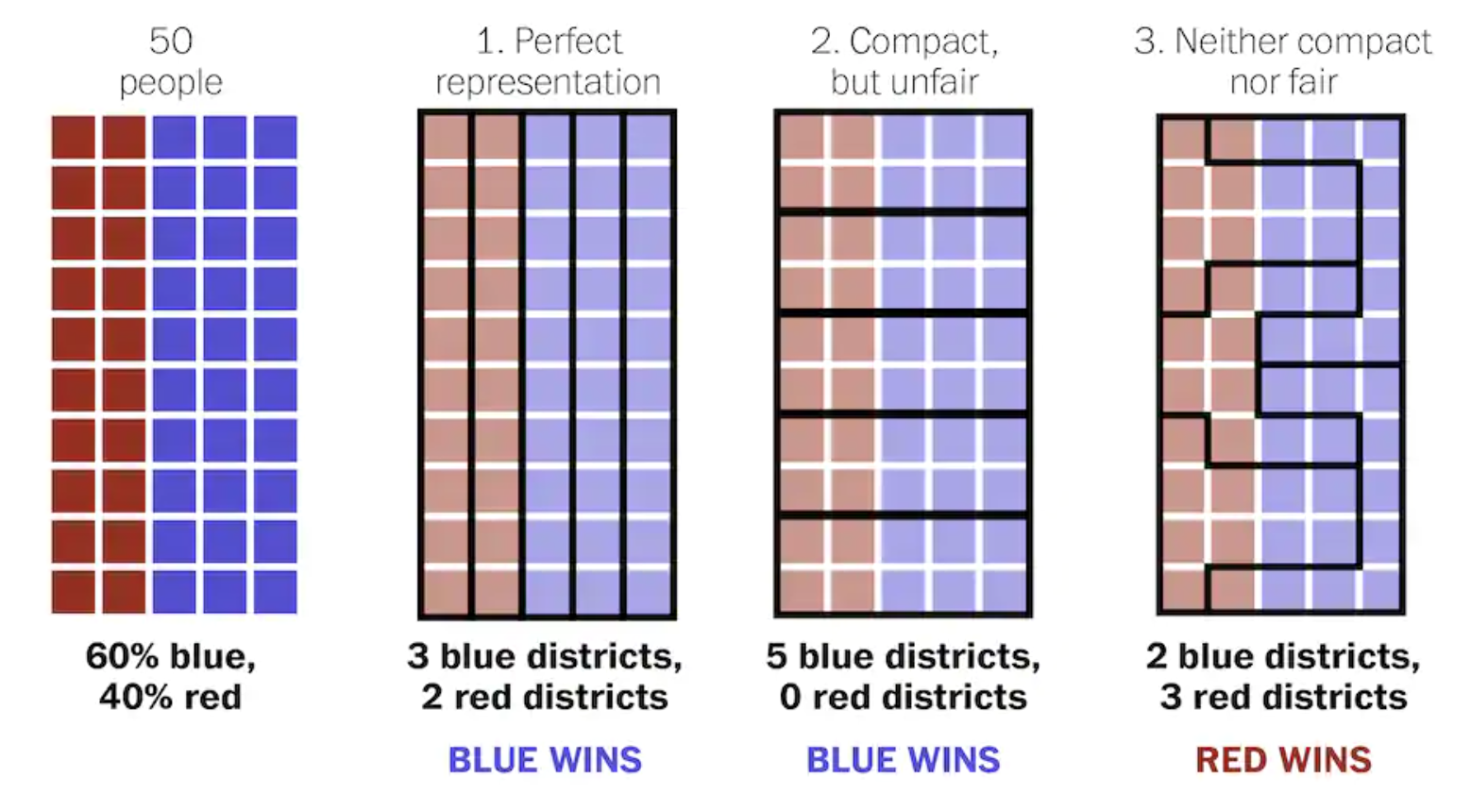

Nor is it the only state-level policy that diminishes certain voters. Lawmakers gerrymander districts, drawing boundaries to spread their supporters, pack their opponents, and reap the resulting advantages.

They’re choosing their voters, and thus deciding elections, years in advance. It’s democracy in reverse.

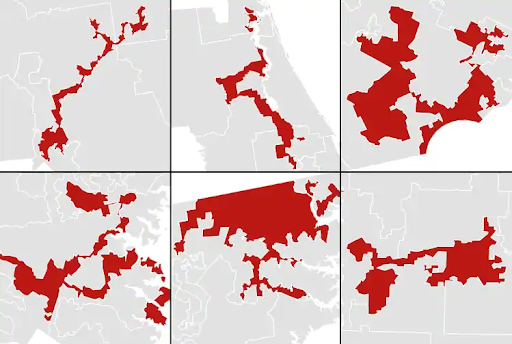

Both parties do it, but Republicans stand out in their scope and shamelessness. A coordinated redistricting effort after the 2010 census handed the GOP a massive advantage in numerous House races, one they are poised to refine after the 2020 census. One glance at some of these districts and the goofiness is obvious.

Redistricting ought to be carried out by independent citizen commissions which, while imperfect, are infinitely better than brazenly partisan politicians warping maps to protect their power.

We aren’t getting the candidates we want. Not really.

You’d think a system built on voter consent would require that candidates win a majority to be elected.

No dice. Most US jurisdictions use first-past-the-post voting, under which candidates need only a plurality. A candidate can win even if a majority of the public detests them and would gladly rally around someone else. Some voters forgo their top choices in favor of a palatable candidate they think can win.

Under ranked-choice voting, voters rank candidates in order of preference. If one candidate wins a majority of first-place votes, they win the election. If not, the last-place candidate is eliminated and their voters are reassigned to their second choice. This continues until one candidate wins a majority.

Ranked-choice voting is the best salve for swelling partisan polarization. Voters could pick third-party and independent candidates without wasting their votes. Democrats and Republicans would be incentivized to appeal more positively to more voters instead of attacking each other, and the intra-party ideological diversity and moderation we’ve lost in recent decades could return.

But more importantly, ranked-choice voting ensures that the candidate with the most support wins. It gives the best possible representation to the greatest number of people. It bestows a mandate to govern.

One person cannot perfectly represent thousands of constituents. And ranked-choice voting has its flaws, namely that it won’t reassign everyone’s vote because the process ends once a candidate wins a majority. But it is vastly better at translating voter preference into elected representation. Congress and the states can and should make it universal.

You don’t vote for president. You vote for strangers.

On November 7, as news outlets called Pennsylvania and the election for Joe Biden, it was hard to ignore Biden’s seven-million-vote margin that, were it the deciding factor, would have spared the country some suspense.

The president of the United States wields unimaginable power and influence, yet we elect them with an archaic system that has virtually no modern analogue. It’s an undemocratic inheritance from founders who feared universal public engagement in civics.

By tying each state’s votes to the number of congresspeople it wields, the Electoral College grants disproportionate influence to smaller states at the expense of larger ones. Wyoming voters, for instance, command more than three times the influence of voters in each of the twenty-one most populous states.

Besides the blatant unfairness of valuing votes unequally and allowing popular vote losers to be president—which has happened twice in twenty years and is likely to happen more often—the College also creates swing and safe states. In safe blue or red states, voters supporting the favored party assume their vote isn’t needed, and voters opposing the favored party assume a loss is certain. Demolishing the College equalizes votes and would likely skyrocket the country’s abysmal turnout.

The solution is a national popular vote. And no, this wouldn’t allow California and New York to decide. That misconception is so far removed from common sense that the objective truth of “everyone’s vote is equal and states don’t play a role” is somehow answered with “but some states will have more power.” It also wrongly assumes that populous, diverse states would be ideological monoliths.

A national popular vote would force candidates to appeal to voters nationwide, as national candidates abroad do. As-is, American presidential campaigns focus on the same eight or so swing states and ignore everyone else. And yes, this includes largely rural states, which are overlooked because they aren’t swing states.

Though the College can be abolished via constitutional amendment, a more feasible solution is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, wherein ratifying states commit to casting their electoral votes for the winner of the national popular vote. The compact takes effect once states holding a majority of electoral votes ratify, at which point the College is retained but rendered irrelevant.

Fifteen states and Washington, DC, which total 196 electoral votes, have passed it. Though the path to 270 would require a few states to cede their outsized influence, the compact would take effect if it were ratified by the nine states where it has passed one or both houses of the legislature. It’s tough but doable.

The Constitution allows state legislatures to select electors as they see fit. The tricky part comes in its prohibition of compacts between states, but court decisions have clarified that this applies to compacts that boost state power at the expense of the federal government or other states. This compact does neither; it is state legislation changing state laws to make every state equally irrelevant to the process. It leaves all voters on equal footing.

Democracy poses many hard questions. Whether the country’s leader should be the most popular choice is not one of them.

The Senate isn’t deliberative. It’s busted.

If a legislature represents cows better than it represents people, it’s time to redesign it.

Such is the case for the US Senate, where Wyoming voters wield sixty-seven times the influence of their California counterparts. A majority of the country’s population is represented by just eighteen senators. While a few other nations feature disproportionately selected legislatures, none are as skewed as ours.

The Founders adopted the two-senators-per-state rule at a time when the country was just the East Coast, and when its population was one-eightieth of what it is now. Today, the Senate favors smaller, predominantly White states so much that it has normalized minority rule.

These problems are exacerbated by the filibuster, an accidental rule responsible for a Dr. Seuss reading on the Senate floor. By allowing senators to speak indefinitely and stall votes, the filibuster ensures that legislation cannot pass without a sixty-vote supermajority to end debate.

It turns smaller states’ outsized control of the chamber into a chokehold. Though some contend it protects debate and the rights of political minorities, it actually allows them to obstruct the majority. There’s a reason the principles it represents have been all but abandoned in European democracies.

In recent decades, Senate productivity has plummeted as filibuster use has skyrocketed. Substantive gun violence, health care, and climate change reforms, among others, were either filibustered outright or dropped because a filibuster would have killed them. While abolishing the mechanism is necessary to break the deadlock, the body needs a bigger remedy.

Congress could divide large states to level out representation. A federal law would give populous states—those with X times more people than the least populous state—consent to divide as long as the state and its residents agreed to it. While it would be tough to avoid gerrymandering—citizen commissions could help—and solve logistical and administrative challenges, it is a promising and constitutional solution.

There is also the nuclear option: abolishing the Senate by constitutional amendment. Though amendments cannot deprive states of equal Senate representation, abolition would be constitutional. Every state is equally represented in a body that does not exist. Senate-specific functions would be given to the House, with the same majorities required to confirm nominees, impeach officials, ratify treaties, and the like.

Per one estimate, 70 percent of Americans will live in just fifteen states by 2050. Thirty percent of the public would control 70 percent of the Senate. This imbalance does not ensure “everyone’s voice is heard.” It doesn’t “preserve states’ rights.” It isn’t federalism as it’s meant to be. It’s just unrepresentative government. It’s one party holding the country ransom despite lacking popular support.

No solution is perfect. But with minority rule in the Senate growing ever worse, the status quo is unacceptable.

You aren’t represented.

Democracy relies on peaceful revolution. At set intervals, we overthrow the government at the ballot box and replace it with one we like better.

Maintaining a vast, populous, diverse democracy is hard enough when everyone is represented fairly. When they aren’t, you risk a less civil regime change.

Every US citizen should be allowed to vote, no matter where they live, what ID they have, or what mistakes they’ve made.

Everyone should be able to rank candidates to best express their preferences.

And everyone’s vote and representation should be weighed equally regardless of where they reside.

These are basic principles, yet we’ve been getting them wrong for more than two centuries. Some were implemented through misguided design, others were shoehorned in later. But either way, we need to address them. We don’t get to jump up and down complaining about political polarization, toxicity, and stagnation without recognizing that it’s a mechanical problem. We have these battles because our rules of engagement take us there. And they’re getting worse.

American democracy probably doesn’t represent you properly. But with a few small tweaks and some large ones, it can.