On the seventy-fifth anniversary of the UN’s formation, Secretary-General António Guterres said that it is “clear that the world has high expectations of us, as the main platform for multilateralism and cooperation on a rules-based international system.” To achieve effective cooperation, the UN Charter sets forth one of the UN’s most important missions as developing “friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures to strengthen universal peace.”

But global change has rendered the UN’s institutional framework obsolete. States, deprived of the postwar context of multilateral cooperation, have found it difficult to work together on a common agenda. Today, global challenges such as climate change and COVID-19 highlight the need to reform the UN Charter for the sixth time. Its framework must undergo a reformation, particularly regarding decision-making within the Security Council and General Assembly.

The UN has achieved plenty, such as the implementation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 or addressing ozone layer depletion in 1987 through the Montreal Protocol. But its bureaucracy lacks citizen involvement and affords disproportionate power to a few powerful countries. These are not in line with current global challenges that require significant compromise and contributions from every nation.

The Role of the UN

The UN Charter mandates the sovereign equality of all member states. This principle—embodied by the General Assembly’s one-country-one-vote system—was an attempt to stray from the era when European states monopolized the international sphere through their colonies.

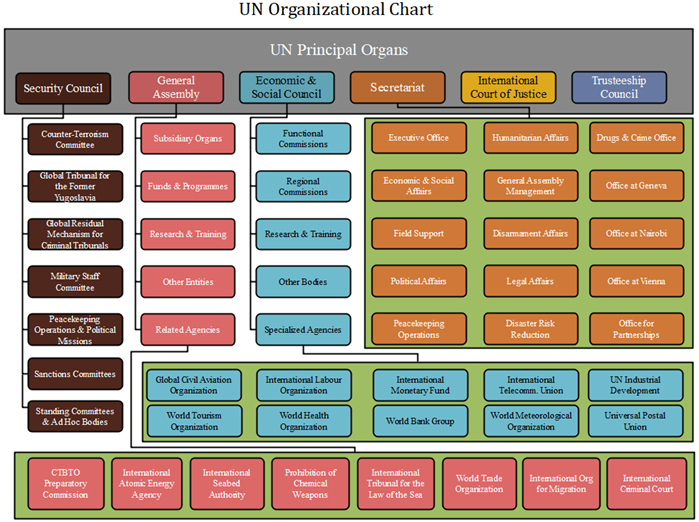

Sovereign equality exists within UN institutions, which include several organs that focus on different areas with varying levels of independence and authority. These sub-organizations form what is often called the “bureaucratic monster” that resists the implementation of decisions and regulations. Due to this complexity and the UN’s weak communication, citizens are often unaware of how these organizations work and how diplomats representing their countries vote. This is something that the current UN Secretariat, led by António Guterres, is trying to reform; the UN has advocated for civic participation and has launched several promotion campaigns that show what it does.

The UN and its leadership have made efforts to combine government and private sector efforts to overcome global challenges such as COVID-19. However, it needs to be more effective when encouraging dialogue among stakeholders, and that starts by reforming the Charter. The UN should proceed with the inclusion of civil society and the private sector in decision-making, especially considering the economic benefits of doing so and the importance of fairly representing civil society.

Reforming the Security Council

At its core, the UN is supposed to be a formal institution of limited powers as well as a generalized system of constitutional principles to govern interstate politics. It can enact nonbinding charters that attempt to organize the international system through voluntary compliance. But absent the approval of the five permanent Security Council (SC) members, the UN cannot implement binding decisions or take any action that would violate a members’ national sovereignty.

The most fundamental issue with the current structure is the disproportionate power given to the SC, which comprises fifteen member states and has binding authority under international law. Although it claims equal sovereignty, the Charter gives SC veto power only to the permanent members: the US, the UK, China, France, and Russia. The SC is unjust given its sweeping legal power, disproportionate focus on traditional security issues, and general disregard for other issues such as humanitarian needs.

Ideological conflicts among the US, Russia, and China stymie the SC’s decision-making. In 1994, Russia vetoed a transport of goods and personnel to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which a year later suffered the Srebrenica massacre. This ethnic cleansing wiped out around eight thousand of the Bosnian Muslim population in the town. Likewise, Russia and China’s decision to veto sanctions on Syria for alleged use of chemical weapons on its citizens allowed the Assad regime to continue violating human rights. This is a serious concern for the UN given the regime’s weapons use violates the 1992 Chemical Weapons Convention, a UN-led endeavor.

Scholars and UN members alike believe that remodeling the SC is a necessary step toward democratic decision making. Secretary-General Guterres stated that the goal must be a “twenty-first century UN development system that is focused more on people and less on process.”

On a similar note, Jeffrey Sachs, the director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, believes that “Asia’s inadequate representation poses a serious threat to the UN’s legitimacy, which will only increase as the world’s most dynamic and populous region assumes an increasingly important global role.” Asia already comprises approximately 60 percent of the planet’s population, and with growing economies such as China and India, there is a high chance it will become the new hub of international relations.

Asia is also home to financial institutions that promote regional development. China, for instance, is pushing economic projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative, which promotes infrastructure development and accelerates economic integration between countries along the route of the historic Silk Road. Beijing also invests in projects in the Asia-Pacific—a region which demands more than $22 trillion for infrastructure through 2030—by way of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank. The bank loaned over $12 billion in 2019 to development, including solar projects in India. There are other initiatives such as the US-and-Japan-led Asian Development Bank, and the $60 billion US International Development Finance Corporation that run similar programs.

Given its influence on global markets, Asia is misrepresented on the SC, holding only one permanent seat while Europe—with only a third of China’s population—has two. Making the SC more diverse will make decision-making more fair.

However, true adherence to the core principle of sovereign equality requires removing the veto power and diversifying the country rotations. This will lead to more inclusion and fewer countries boycotting decisions. To that end, instead of state representation, the UN could include regional organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations or the European Union to make the body more diverse and proportional.

Inclusion and Democracy

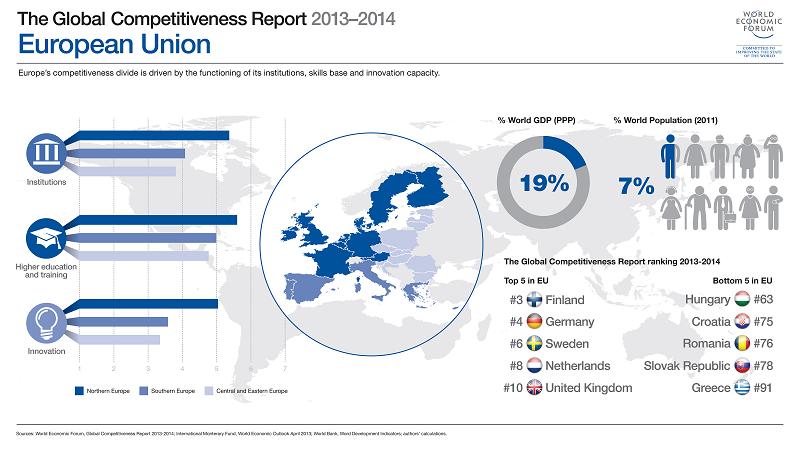

The European Council, the executive body that made Europe a model of integration, employs a more democratic model. Although it uses the same representation method as the UN General Assembly, it differs in that its decisions are binding. Member states also get a vote in proportion to their population and monetary contributions to the EU.

The UN can employ a similar organizational style to be more democratic and respect the diverse demographics that its members represent. The SC already employs a one-country-one-vote system, so making the General Assembly proportional will make the UN look more like the EU—a proportional parliament and a more executive commission.

In the EU, three institutions represent different perspectives, something the UN model disregards. The European Parliament is the legislative branch composed of democratically elected representatives from every member state; the European Council is the body composed of governments of individual member states; the European Commission is the overarching body which proposes new laws and represents the organization at international conventions.

The UN lacks the equivalent of a European Parliament—directly elected representatives who are accountable to voters. While not the world government, the UN is the forum for discussion on global issues related to health, human rights, climate change, and other challenges that require international cooperation. A democratically elected body can act as a catalyst for a more consensus-driven, inclusive UN.

The UN General Assembly’s disproportionate system can also be reformed by switching to the European Parliament’s “weighted voting” system. Under it, the UN’s 193 members would be allocated voting power proportional to their population, GDP, and contributions to the UN budget. To an extent, this will favor wealthier and more populous states. The UN should therefore establish a subsidiary body—the Parliamentary Assembly—which, like the US Senate, would allocate the same number of seats to each country regardless of its economy and population.

Public–Private Partnerships and the UN Parliamentary Assembly

A more representative UN would incentivize international cooperation outside the traditional scope of UN jurisdiction. One way is through public–private partnerships, a form of “international networked cooperation” (a term coined by Northeastern University Professor Denise Garcia). This includes the COVAX program, which harnesses the power of 172 governments—together with private organizations and nonprofits such as the Gates Foundation—to issue and distribute a COVID-19 vaccine across the globe. Fifteen African countries have already received vaccines from this institution.

The UN must also include ordinary citizens in its decision-making and legislating. One proposed solution is the Parliamentary Assembly, already supported by 150 civil societies, 123 countries, and more than 1500 parliamentarians. This institution would be similar to the European Parliament and can easily be established through the UN Charter, which empowers the General Assembly to establish subsidiary organs with a simple majority vote.

The Parliamentary Assembly would not only allow citizens to choose their representatives in the national elections—which EU citizens do for the Parliament every five years—but would also force representatives to fulfill campaign pledges in order to get reelected. It could emulate the work done by national citizens’ assemblies, already making a significant effort to influence national policies and laws. Members of such an assembly are part of civil society and can advise their political representatives.

One example is Ireland, where citizens’ assemblies have lobbied the government to pass laws. In 2012, the ninety-nine-person Constitutional Convention of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly recommended legalizing gay marriage. Its success by way of a 2015 public referendum marked the first time a citizens’ assembly had accomplished the feat.

In 2017, the Citizens’ Assembly also successfully advocated for legalized abortion. Likewise, the Parliament of the German-speaking community in Belgium has included citizens’ assemblies in its decision-making on a permanent basis. Similar efforts are popping up everywhere from South Australia to Madrid to Gdańsk.

The formation of a new advisory body should not provoke fierce opposition; precedent has been set by more than four thousand NGOs who already have consultative status in the UN Economic and Social Council, the UN’s central body for sustainable development. The ideal assembly would cover issues of global concern and consult other parts of civil society such as expert groups and scientists.

Reform Should Happen Now

The UN has already garnered significant global commitments through initiatives such as the Millennium Development Goals and the newer Sustainable Development Goals targeting global challenges. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic indicates, much more has to be done.

For starters, the UN should address the democratic deficit hindering progress on collective decision-making by focusing on institutional reform. In order to achieve a just, democratic system that includes every state, the UN should continue demanding reform, resources, and equal representation.

It is time for leaders to be held accountable for their actions and view global issues beyond their country’s self-interest. States cannot advance in isolation—as the pandemic and climate change have shown, we must address global challenges as one world and as one community.