History shows that capitalism is color-blind.

Though not even three hundred years old, free-market capitalism has revolutionized the world. Its positive influence on general economic prosperity is undeniable; most successful countries have adopted some form of free market. However, a growing body of scholars criticize capitalism for its supposed corruption by historical inequities, most notably racism.

This theory could not be farther from the truth. Free markets discourage discrimination, actively encourage tolerance, and undermine all sorts of racial supremacy. Historically, capitalism has been a force for equality, not oppression.

The Birth of Capitalism

Born out of Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776, capitalism merged enlightenment ideals of self-ownership and liberty with economic theory.

At the time, mercantilism prevailed as the most widely accepted system of trade. Positing that global wealth is static, mercantilism drove early nations—hoping to accumulate the greatest share of wealth—to maximize exports and minimize imports.

Capitalism flipped this on its head, suggesting that protectionism limits the variety of goods available to consumers, restricts competition, and inflates prices. According to free-market theory, individual enterprises acting out of self-interest could engage in mutually beneficial trade for the betterment of all. David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage later elaborated on the merits of specialization and trade.

Capitalism requires certain conditions to function properly. People must be allowed to obtain and accumulate property, as well as trade it with other consenting parties, within a competitive and free environment. These conditions incentivize innovation, increase worker productivity, and allow people to access goods they cannot produce themselves.

The unique characteristics of capitalism are associated with not just the greatest rise in prosperity in human history, but also the modern shift toward racial tolerance.

Free Markets Need Free People

While some writers have compared capitalism and slavery, in reality, the systems are antithetical to one another and are built on different economic and social functions.

From the capitalist perspective, slavery stymies innovation by eliminating peoples’ prospects of wealth accumulation altogether. Smith commented that—because the fruit of slave labor goes only to the master—slaves are careless about the quality of their work. Slaves’ aversion to innovation helps explain why nearly all of society’s greatest works have been the discoveries of freemen. Slavery also flies in the face of “consensual trade” since slaves do not voluntarily contract their labor.

Smith’s adherence to free-market principles led him to advocate for the cultivation of Britain’s colonies by freemen instead of slaves, a proposal that wouldn’t be realized for another seventy years.

Capitalism’s conflicts with slavery contributed to the British abolitionist movement, which influenced American abolitionism. Quaker businessman James Cropper—armed primarily with the contention that “slave labour could not compete with free labour on equal terms”—was largely responsible for the revival of anti-slavery sentiment in Britain. One scholar even described Adam Smith as a “generative site of abolitionist ideology.”

Conversely, prominent defenders of slavery adopted explicit anti-capitalist rhetoric. George Fitzhugh, a well-known slave master, opened his manifesto Sociology for the South with the line, free society’s “fundamental maxim Laissez-faire and ‘Pas trop gouverner,’. . . are at war with all kinds of slavery.”

Color-Blind Capitalism

In a free-market economy, discrimination carries dire consequences at the macro and micro levels.

At the macroscale, discriminatory employers force laborers to occupy lower-paying positions they are overqualified for, limiting employee consumption potential and productivity. Because consumption drives economic growth, widespread discrimination curtails prosperity for everyone. Simultaneously, reduced worker productivity increases production expenses, results in cost-push inflation, and burdens consumers financially. Further, limiting the labor supply to workers free from discrimination artificially inflates wages, leading to more cost-push inflation, higher prices, and an increased burden.

At the microscale, individual businesses that discriminate against customers miss out on profit and valuable networking. Employment discrimiation limits hires to less qualified and less productive applicants. For these reasons, shops that discriminate will inevitably need to raise prices above those that don’t, reducing their appeal to consumers. Fewer consumers means less profit, higher prices, fewer consumers, and so on. In short, discrimination is a costly business that is rooted out over time by market competition.

Beginning around 1865, southern states enacted Black Codes and Jim Crow laws to preserve racial hierarchies. These laws conflicted with the freedom essential to a capitalist economy. They restricted the type of businesses African Americans could own and buy from, when they could safely visit commercial areas, and even how many people could gather at a specific time.

Alabama made it unlawful for restaurants to serve White and Black people in the same room, prevented White nurses from tending to non-White patients, banned interracial pools, and segregated restrooms. Mississippi went even further, declaring any public support for social equality or intermarriage a misdemeanor punishable with a $500 fine ($12,759 in today’s money) and up to six months in prison.

Despite these legal obstacles to racial reconciliation, the substitution of the South’s slave economy with a more capitalistic one provided African Americans with new opportunities and countered culturally-embedded racism.

Sears: A Case Study

Under Jim Crow, Black Americans operated primarily as sharecroppers within larger systems of convict leasing and debt peonage. White landowners took center stage in the day-to-day lives of Black sharecroppers. They leased equipment, seeds, fertilizer, and food to Black tenants on credit until after the harvest, at which point the tenants had to reimburse the landowner.

Unpredictable harvests and unreasonably high interest rates deprived indebted tenants of what little wealth they had. In effect, Southern slavery continued under a different name.

Without capital, Black sharecroppers had no choice but to shop at local general stores—often run by their landlord—that could lend them products on credit. These stores were strongholds of White supremacy, serving White customers first, racially biasing their loans, and forcing Black Americans to purchase low-quality goods.

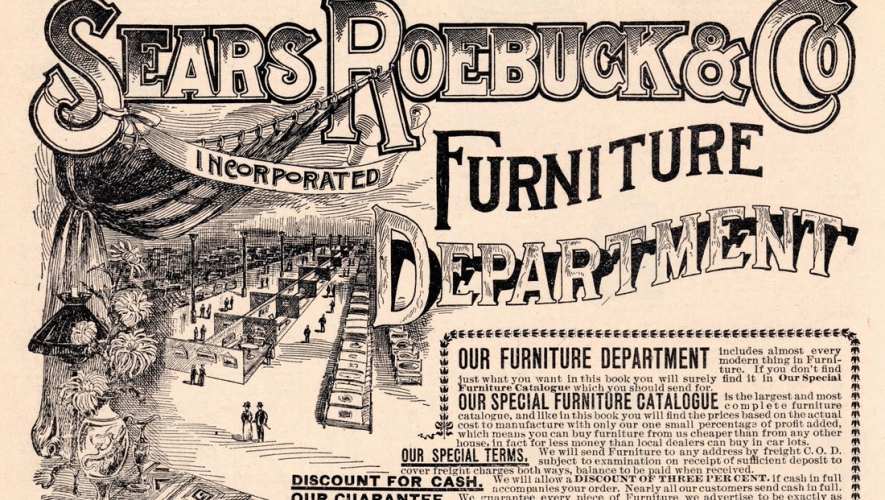

That is, until Sears. Sears started as a mail-order retailer with the ambitious aim of outcompeting Montgomery Ward, an established and popular catalog. Sears’s novel business strategy: letting consumers purchase from a catalog on credit.

For the first time, African Americans could access the same goods as White Americans, and a similar consumer experience. Once Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck —the founders—realized the profit potential of equality, they bought in full-scale to the subversion of racial hierarchy. Sears added instructions to their catalog detailing how to ask postmen for orders, allowing Black Americans to avoid ordering goods through general stores that often refused to provide money orders or stamps. To accommodate barely literate and overwhelmingly Black customers, they also filled orders no matter their legibility.

Even those African Americans that avoided peonage benefited from Sears’s business model: it provided a method of shopping without humiliating interracial confrontations.

Sears and Roebuck were no activists for equality, but they understood that in America’s free-market system, money lies in the hands of consumers. As historian Louis Hyman describes, Sears “wasn’t a self-conscious social enterprise that was designed to fight white supremacy; it was a way of making money. And it did make money! And it helped black people at the same time.”

Sears and Roebuck may be the protagonists of this story, but capitalism enabled their prioritization of profit over prejudice, undermining White supremacy in the process.

Streetcars: A Case Study

Capitalism’s war against Jim Crow didn’t end with Sears.

Plessy v. Ferguson lives in infamy as one of the most despicable court cases in American history, with a legacy of hate, destruction, and oppression. The majority upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine, allowing for ostensibly equal racially segregated facilities. But while most schools teach Plessy’s outcome, few relay its origin.

Homer Plessy—the defendant—was recruited by professionals from New Orleans’ mixed-race society and the East Louisiana Railway company to challenge the Separate Car Act of 1890, which required “equal, but separate” train cars for the different races. Like Sears, early railway companies were not stacked with proponents of racial equality. Instead, businesses simply sought to avoid the economic costs of discrimination—specifically, adding train cars to accommodate segregation.

Louisianan railways weren’t the only ones to resist segregation. In Georgia, Texas, Florida, Alabama, and Tennessee, streetcar companies refused compliance with laws similar to the Separate Car Act. Only after years of government pressure did the cost of refusal outweigh the cost of discrimination.

The Augusta Railway and Electric Company outright ignored Georgian segregation law for almost a decade, despite a nearby police commissioner pressing them to comply. Even when outrage erupted in response to the shooting of a White man on a crowded streetcar, the company still resisted. City council members and local newspapers’ calls for compliance forced it to abide by segregation in technical terms, but these institutions should have watched what they wished for.

Hoping to anger White passengers and generate anti-segregation sentiment, the Augusta Railway and Electric Company carried out enforcement in the most literal ways possible; for instance, conductors denied the requests of White passengers to smoke in the back of the car, requiring them to remain in the front and anger other White passengers. Streetcar companies in Savannah, Georgia were no different. The Seaboard Air Line and Thunderbolt lines both avoided segregation for years.

In Houston, Texas, a slightly different story played out. It isn’t clear whether Houston Electric Railway officials initially fought the passage of Houston’s segregation ordinance, but they certainly demanded it be overturned. Black citizens of Houston boycotted the railway almost immediately after the ordinance’s passage, spurring company manager H. K. Payne to beg the city council for an amendment.

Like in Texas, Floridian streetcar companies opposed segregation after the Black community boycotted their services. The Jacksonville Street Railroad Company didn’t enforce segregation for years after it was legally mandated and wrote a letter to the city council requesting alterations to discriminatory laws.

Alabama’s streetcar companies followed the Georgian and Texan models. When Alabama passed its first segregation laws, streetcars in Mobile refused to segregate riders, and streetcars in Montgomery initially enforced segregation but eventually caved to boycotts.

Memphis Street Railway officials bitterly contested Tennessee segregation mandates. The streetcar company employed a unique strategy, making plans to abide by segregation law before purposefully pleading guilty to violating it and requesting its constitutional review. Eventually, in a victory for the streetcar company, the law was ruled unconstitutional.

Encouraging Equality

Skeptics of free-market capitalism’s relationship with racial tolerance point out that people don’t always behave rationally. That is, they may discriminate even if it is not in their best interest to do so. To a certain extent, this is a fair critique.

Capitalism is not a cure for racism. Racism can survive within capitalist systems if its participants are willing to absorb the costs. But this critique also goes too far, implying that because some people don’t act rationally, no one does. In a free-market system, those who incur costs for irrational actions will be outcompeted by those who make rational choices. Only rational, indiscriminate actors will be left standing. Government intervention may be necessary to preserve competition, but should be used in moderation.

There are historical paradoxes related to this critique that seemingly complicate the “capitalism promotes equality” argument. For instance, despite the South’s forced adoption of truer capitalism, employment segregation in some industries worsened between Jim Crow and the start of World War II. But these purported debunkings do not reflect peoples’ willingness to absorb economic cost; they reflect a cultural racism so entrenched and extreme that it led many to believe discrimination is rational. Scientific racism, a form of social Darwinism, was widespread during this period. Many White Americans falsely believed that African Americans were inferior workers with limited intellectual capacities. Such misguided information allowed White firms to discriminate in employment while simultaneously maintaining that they maximized productivity.

Employment segregation worsened in this period not because of free-market forces, but because most of high society believed one race to be inferior to another. In other words, segregation would have worsened during this period regardless of the economic system in place.

Free-market forces actually countered this deeply embedded cultural racism. Even as Southern segregation worsened, Northern agents recruited Black employees in the South. This strategy expanded the Black middle class by providing new economic opportunities. It also exposed businesses to the falsity of racial stereotypes, the real productivity of Black workers, and the importance of racial tolerance. In Cincinnati, businesses that hired African American workers before 1916 doubled their number of Black employees when World War I increased demand for labor. Once businesses became aware of discrimination’s costs, they moved—to a certain extent—toward integration.

World War II and post-war advocacy accelerated these trends. They provided a significant shock to the economy, increased demand for Black laborers nationwide, reduced southern employment segregation, and raised Black wages. After the war, an established Black middle class experienced further integration thanks to its influential purchasing power.

Counterfactual racist beliefs have dominated all of history. These beliefs resulted in discrimination and segregation under every economic system. But free-market forces—accelerated by economic shocks—uniquely contributed to their dissolution and moderated their impacts. By punishing discrimination, the free market encourages equality.

Have Faith in Freedom

Despite capitalism’s successes, socialism is experiencing a resurgence in popularity, with four in ten Americans reporting that some form of it would be good for the country. Particularly, Democrats have a more positive view of socialism than capitalism, with many citing its promotion of equality to justify their position. Major publications have bought into this narrative, pushing pieces that attribute contemporary corporate practices to bookkeeping by slave owners, among other reductio ad hitlerum–esque arguments.

But when it comes to fairness, only free-market forces have tangibly opposed discrimination. Socialist plans, while purportedly committed to racial harmony, have provided few opportunities to marginalized communities.

The Soviet Union was no kumbaya of ethnic harmony. While officially endorsing “[c]omplete equality of rights for all nations,” the country ethnically cleansed German, Korean, and Chinese people. As much as one-fourth of the Ukrainian population—suspected of being kulaks (prosperous farmers)—would eventually starve thanks to discriminatory government food production quotas. More than eleven million died of famine and dekulakization.

Cuba has also faced challenges with equality. Cuban leadership was 71 percent White in 2005, a stark contrast with its 62 percent Black population. Even worse, a majority of Black Cubans were unemployed, and they overwhelmingly blamed “racial discrimination” for their plights, which included twenty-five years of worsening impoverishment. Writing in 2016, Kimberly Lyle, who is of Cuban descent, asked her readers, “[d]o we care that black Cubans still can’t enter many hotels or restaurants?” Ironically, Castro announced shortly after Cuba’s communist revolution in 1959 that racism had been solved.

Compare the case of Cuba to that of America. Despite America’s social flaws, between 1960 and 1993, the Black American median family income rose sixfold. This precipitous rise can’t be explained by the Civil Rights Movement’s legal victories since similar economic gains were made between 1939 and 1960. Instead, it is attributable to free-market forces—accelerated by economic shocks—that combated prejudice and granted opportunity. In 2013, when Gallup asked Black Americans if they thought that racial job, income, and housing disparities mostly stemmed from discrimination, a majority said they thought it was mostly due to something else. Today, there continue to be many reasons for Black optimism in America.

Prejudice is a universal phenomenon. The difference between socialism and capitalism is that socialism empowers governments to act on or ignore their prejudices, while free-market capitalism restricts government power and incentivizes equality. We must have faith in freedom—and reject calls for anti-capitalistic top-down economic control—for American prosperity to reach all its citizens.