Imagine, if you will, four Muppets running for a Senate seat.

To the left is Beaker, a champion of single-payer health care, progressive taxation, and criminal justice reform. Despite his debilitating speech impediment, Beaker captivates audiences through his simple campaign slogan: “Not mee, us.” His campaign manager, Dr. Bunsen Honeydew, describes Beaker as “the harbinger of progressive prosperity for our country.”

Kermit joins him on the left, though he’s more moderate. He favors a public option but not universal health care, reforming but not defunding the police, and piecewise climate change action because “it’s not easy being green.” Jason Segel recently endorsed Kermit, calling him “one man of a muppet.”

Libertarian Rowlf the Dog ardently opposes what he calls “the shock collar of government regulation.” He favors the legalization of marijuana, individual rights, and a government small enough to drown in his water bowl.

Then you have Miss Piggy, millionaire conservative cosmetics mogul. The pro-life, pro-police Piggy has backed tax cuts for her wealthiest constituents and the construction of a concrete pen on the southern border. Piggy most recently entered the world of high fashion with her “sexy lingerie PPE,” or basically just mesh masks.

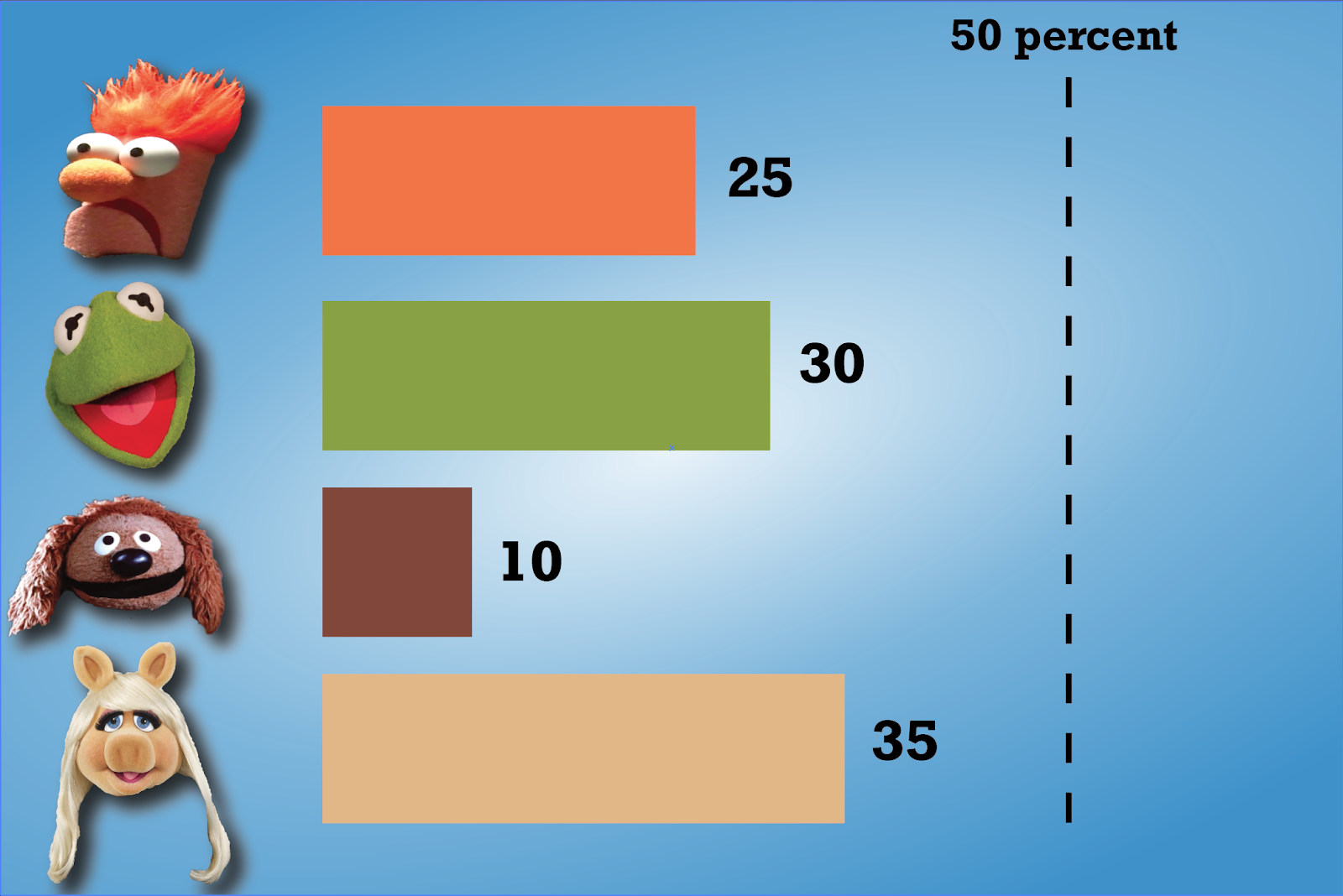

The results look like this:

Under first-past-the-post voting—which is used for nearly all elected offices in the United States—Piggy wins despite earning less than half of the votes.

But what if we want a winner with majority support? This time, we’ll let voters rank as many candidates as they like in order of preference. If a candidate gets more than 50 percent of first-place votes, they win. If not, the last-place candidate is eliminated and their voters are reassigned based on their second choice. This continues until a candidate has a majority.

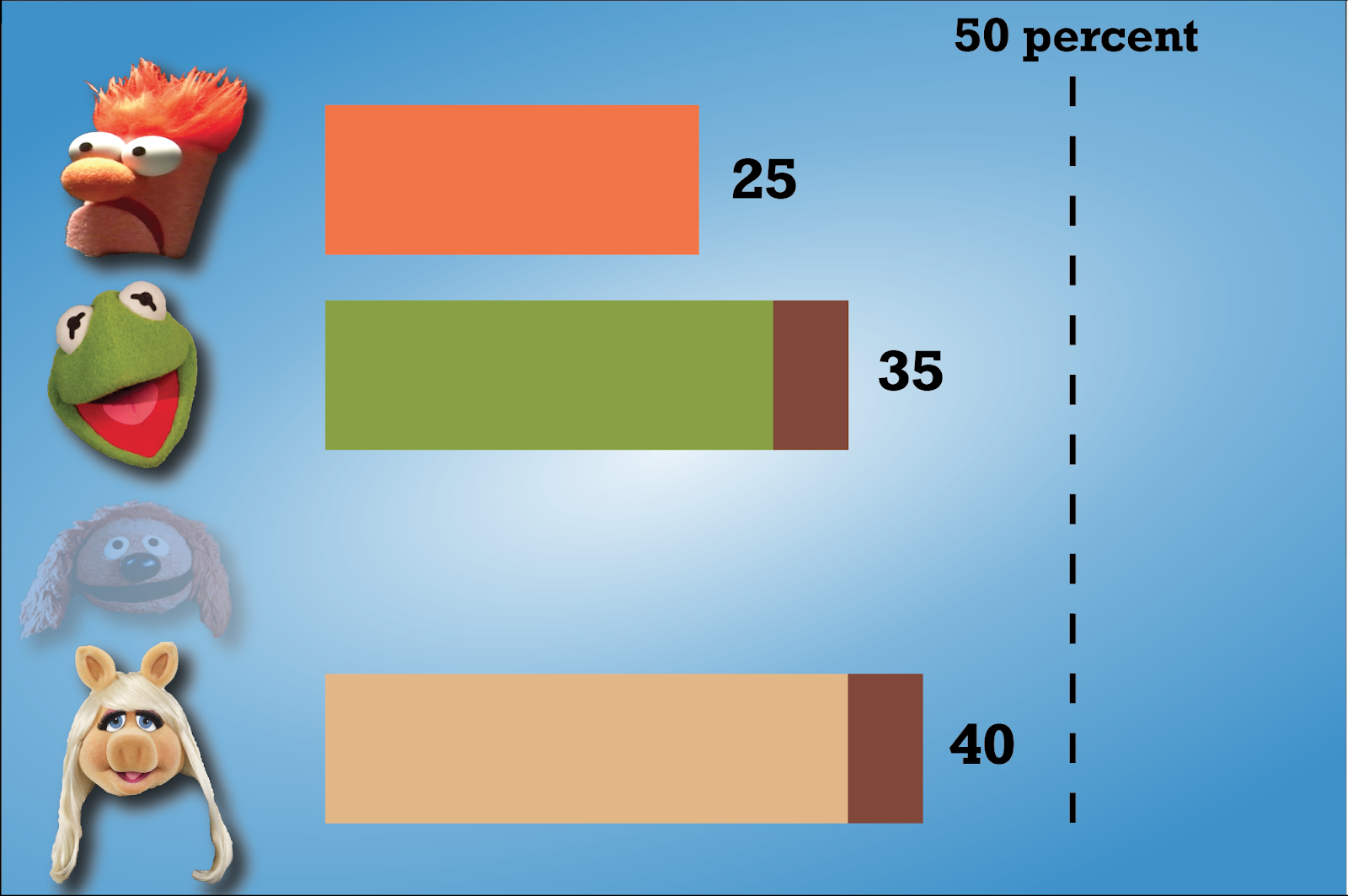

Assuming the first choices from the above example remain the same, Rowlf gets the fewest first-place votes, so let’s reassign his voters:

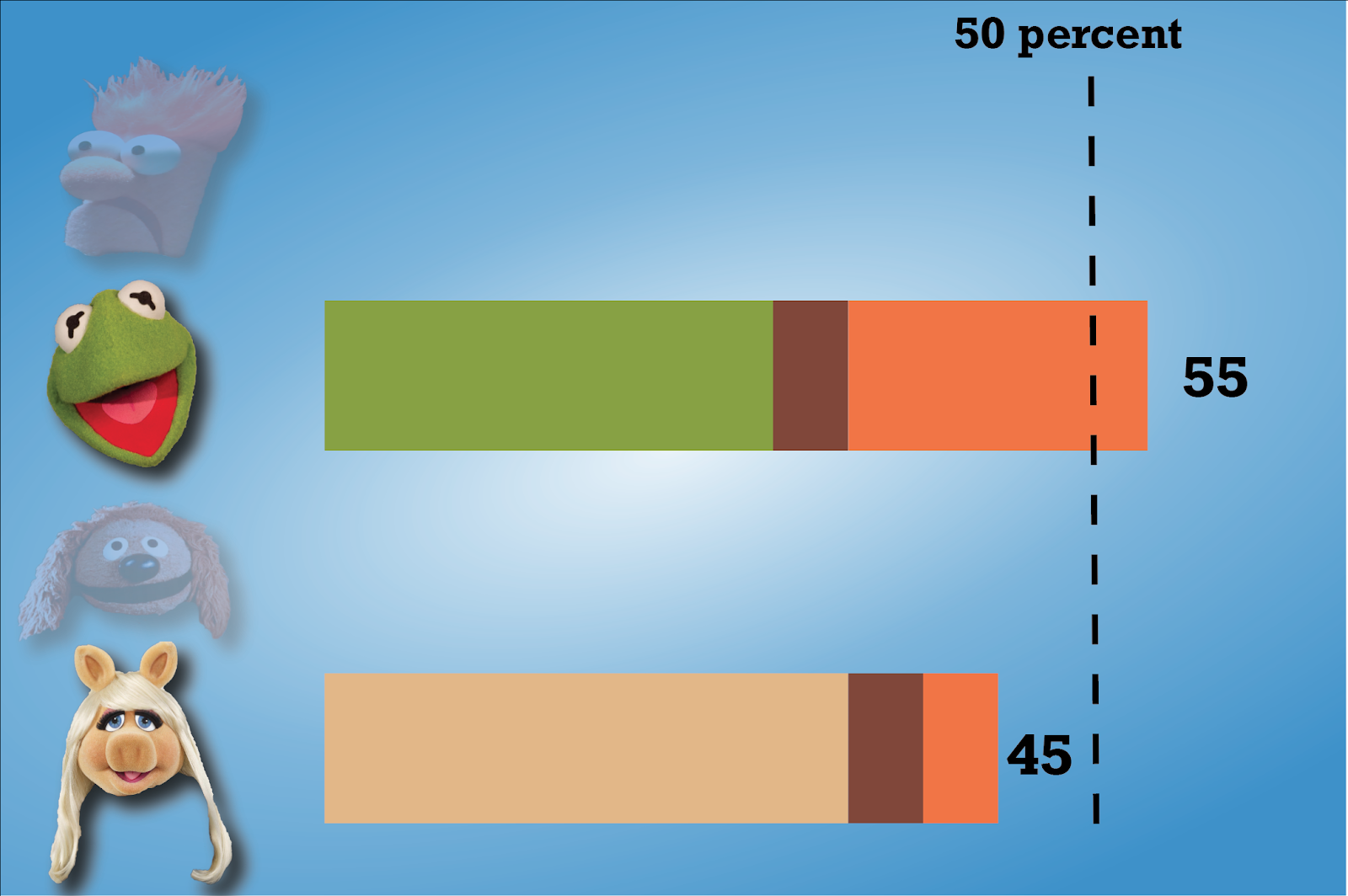

Half the libertarian’s votes go to the conservative Piggy, the other half to center-left Kermit. There is still no majority. So we reassign the progressive Beaker’s voters to their second choice:

Almost all progressive voters prefer a left-center candidate to a conservative one, so Kermit takes the seat. Allowing voters to rank the candidates yielded a winner with the greatest overall support.

Some cities and counties use ranked-choice voting (RCV) for local elections, party primaries, or overseas voting, and Maine uses it for statewide elections. But most jurisdictions don’t, and that’s a shame, because RCV would help to solve myriad problems with voting and representation.

Under first-past-the-post voting, candidates can win with a plurality of votes, so the winner doesn’t necessarily represent the popular will. A majority of voters might despise them. RCV ensures that the most-supported candidate wins, either outright or because they are many people’s second or third choice. It also ensures that the office holder has a mandate to govern.

RCV eliminates first-past-the-post gamesmanship, wherein voters select the candidate they think can win and not the one who best matches their political ideology, values, and priorities. This is a large reason why no candidate other than a Democrat or Republican has seriously contended for the presidency in the last century, and why third-party and independent politicians have rarely had a meaningful presence in Congress. Their supporters typically waste their votes on candidates who can only play spoiler for another candidate, not win themselves.

In a diverse nation of 330 million people, two parties cannot provide enough ideological variance to represent the public well. RCV can help to break the duopoly. Reassigning votes lets people select their first choice without worrying about wasting their vote, thus elevating candidates with popular proposals. Third parties could gain traction and win office.

It would also force Democratic and Republican politicians to campaign and govern differently. First-past-the-post creates an environment overflowing with negative partisanship, one in which the parties launch attacks, move further apart, and care only about beating each other. Republicans become more extreme because they are afraid of primary challengers running to their right. As Republicans fall into line, Democrats, faced with inherent electoral disadvantages in the Electoral College and Senate, must appeal to moderates and progressives because they can’t afford to alienate either group.

It wasn’t always like this. From the 1960s to the 1990s, both parties boasted more ideological diversity than they do now. But close first-past-the-post elections led to top-down party leadership, lockstep voting, the destruction of bipartisan deals, and the erosion of checks and balances. The resulting gridlock forces presidents to use executive authority more, thus strengthening the president, making presidential elections more important, driving partisanship, exacerbating gridlock, and so on.

RCV would make a huge dent in this problem. Candidates would be incentivized to reach out to more voters and earn second-place votes too, making negative campaigning and extreme stances far less enticing. Elected officials are more likely to be moderate, encouraging collaborative lawmaking instead of obstructionism. And more women and people of color run—and win—in RCV constituencies.

It likely would increase voter enthusiasm and engagement in a nation whose voter turnout lags behind most other developed democracies. Americans are more likely to sit out an election because they dislike the candidates than for any other reason. More than a third feel like no candidate represents their views. Sixty percent want a viable third party. The defensive and strategic voting that first-past-the-post encourages will not energize these people. By contrast, most voters in this year’s ranked-choice party primaries took advantage of ranking options and voiced their support for RCV, saying they enjoyed voting more and felt more powerful.

Under the Constitution’s Elections Clause, Congress can establish nationwide RCV for congressional elections. States can do so for any type of statewide election, as Maine did. Between now and November 3, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Alaska have a chance to establish RCV for certain types of elections.

In Massachusetts, Question 2 would begin RCV in 2022 for most state and federal offices, but not for presidential and local elections. Not perfect, but a strong start.

Last month, Massachusetts voters got a perfect demonstration of RCV’s value, especially in races with crowded fields. Nine Democrats ran in the Fourth Congressional District primary, the victor of which would face an easy path to Congress. Jake Auchincloss won with just 22 percent of the vote, topping the runner-up by just one point. We will never know whether he would have won an election that accurately gauged the voters’ will. (Seven of the nine candidates, including Auchincloss, support RCV.)

Democracy is supposed to be rule by the majority. Under first-past-the-post voting, we are vulnerable to rule by the plurality. Establishing ranked-choice voting for some elections in some states is a welcome start, and Massachusetts voters should absolutely vote “yes” on Question 2. But to fully realize all the benefits discussed above we must implement ranked-choice voting for every election in every state. Only then can we have the representation we deserve.