Through patterns of industrialization and globalization, humanity has built planet-altering power. Daily activities as mundane as making coffee in the morning increase our chemical and ecological footprint. Sea levels rise at a startling rate of over an eighth of an inch per year and our oceans have lost two percent of their oxygen in half a century.

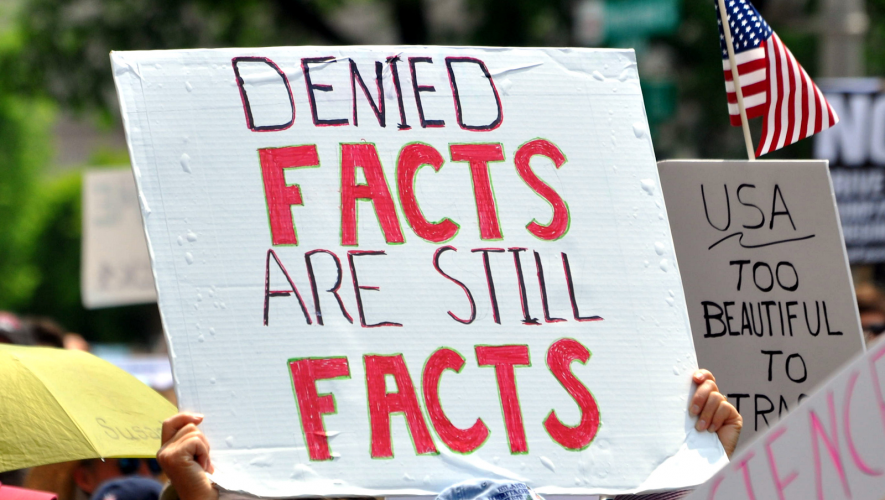

The average American produces seventeen tons of carbon every year, threatening the future of our species. Although two-thirds of Americans believe the United States “is doing too little to reduce the effects of global climate change,” some ignore irrefutable science.

America’s ongoing failure to act decisively on climate change does not stem solely from petty partisan bickering. Despite the concerned majority, many Americans oppose climate science. While this may seem surprising, it is part of a long tradition. Fundamentalism, populism, and anti-intellectualism have plagued American partisan politics for decades, breeding a predictably myopic and individualistic attitude that promotes climate change ignorance.

Hofstadter’s Theory of Anti-Intellectualism

Richard Hofstadter is one of the most prevalent names in the discussion of anti-intellectualism due to his seminal 1963 work, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. Hofstadter characterizes intellectualism as a thought process that “accepts conflict as a central and enduring reality.” It also understands that compromise is a continuous process and that total partisan victory is unachievable. As such, it sees things in degrees and is sensitive to nuance.

Hofstadter’s intellectualism cannot be realized solely through education or intelligence—it is a fundamental system of thought that challenges any and every ideology through debate and discourse, using evidence and fact as its basis of reasoning. Thus, partisanship, ideological politics, corporate interests, and religious fundamentalism have historically been antithetical to Hofstadter’s intellectualism.

Countless instances in American history exemplify a pattern of anti-intellectualism. In 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s baseless Communist fear-mongering sparked the fervent Second Red Scare. After Rachel Carson published Silent Spring in 1962—chronicling how indiscriminate pesticide use damages the environment—pesticide corporations accused her of heralding a return to the “Dark Ages.” Even modern conspiracy theories like Flat Earthism, which riddle pop culture, draw heavily from the rejection of science. These continual rejections reflect anti-intellectualism, since climate change reform would challenge America’s long-standing energy infrastructure and reform industrial regulations.

Hofstadter characterizes anti-intellectualism as a cultural distrust of intellect and a belief that the study of science, literature, and the arts is politically motivated and reprehensible. It draws heavily from emotional appeal and disregards critical thought, facts, and analytical reasoning.

Hofstadter poses that the conflict around anti-intellectualism is that of class warfare because of the many hierarchical barriers—access to education, education quality, socioeconomic status—between “intellectuals” and “non-intellectuals.” The intellectual class is elite in its thinking and functioning; consequently, modern American anti-intellectualism draws largely from a populist platform of anti-elitism.

Anti-Intellectualism as a Political Platform

Hofstader’s characterization of anti-intellectualism provides a lens to analyze climate change denial under a broader populist rejection of science. Strong individualism and a uniquely American hyper-libertarianism assemble a stubborn public attitude that rejects any restriction of “freedoms” and “liberties” under reformed climate policy.

However, modern anti-intellectualism is what truly prevents climate reform from gaining political traction—it channels a populist anti-elitism that oversimplifies or disregards humanity’s ecological footprint, attributes climate statistics to natural planetary change, and rejects experts using confirmation bias and the public’s fear of the unknown.

In his 1991 book, Three Kinds of Anti-Intellectualism: Rethinking Hofstadter, Daniel Rigney expands on anti-intellectualism’s definition. He discusses what he calls “unreflective instrumentalism,” beliefs and behaviors that value knowledge only when it leads directly and immediately to material gain. Unreflective instrumentalism greatly conflicts with climate policy, as it allows corporate interests to take the reins of democracy.

Corporate machines—the only industries that truly stand to gain from the rejection of climate science—take advantage of the public’s ignorance to perpetuate materialist consumer culture. Rightly viewing the broad changes of proposed climate reform as threats to its profits, corporate America pushes instead for corporate-friendly environmental legislation. These institutions focus on short-term losses, ignoring climate change’s long-term, irreversible effects.

Corporate interest groups foment anti-intellectual culture by delegitimizing climate science. These institutions produce overtly anti-climate media streams that irrationally conflate climate reform with an infringement of rights. When the US Virgin Islands Attorney General subpoenaed a non-profit think tank to support his Exxon Mobil fraud investigation, the American Legislative Exchange Council equated it to an attack on free speech. The corporation-dominated political interest group asserted that this was “one of the greatest risks to free speech today,” spinning the narrative from a fraud case to a First Amendment one.

However, corporations are not the sole vehicles for climate change anti-intellectualism; many politicians have benefited from engaging in these populist narratives, directly contributing to an ideological culture that hinders climate reform.

Donald Trump’s presidential platform, which is rife with populist narrative, serves as proof of anti-intellectualism’s political sway. In April, Trump showcased this rhetoric once again by claiming that an anti-malarial drug could combat COVID-19; one month later, he mischaracterized peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters as “thugs.”

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s anti-intellectual dog whistling extends into climate change. He claimed that wind turbine noise causes cancer and that climate change is a “hoax” created by the Chinese government. His campaign advisor echoed this rhetoric, characterizing federal climate change programs as “politicized science.” Trump’s success illustrates that anti-intellectualism is closely tied to political positioning and rhetoric.

Populist anti-intellectualism is a deeply problematic, highly effective political platform. While it has helped politicians like Trump gain traction, it discourages productive democratic discourse, inhibits constructive belief revision, and prevents necessary reform. For climate change, this is especially dangerous, as anti-intellectualists attempt to silence the voices of desperate climate scientists.

Anti-Intellectualism and Climate Partisanship

This discussion of Hofstadter begs an important question: does anti-intellectualism play a direct role in partisanship and the two-party divide in American climate politics? Nisbet, Cooper, and Garrett’s 2015 psychological study indicates that it does.

The study recruited 1,500 participants throughout the country and gauged their behavioral and psychological reactions to science topics that challenged their existing partisan beliefs. It revealed that conservatives were more likely to experience negative affective responses and exhibit stronger resistance to persuasion than their liberal counterparts. The authors concluded that conservatism is a relatively strong predictor of an anti-intellectual distrust towards scientific experts.

Gordon Guachat’s 2012 study tested a 2005 claim that American conservatives have become increasingly skeptical and distrustful of science. He found that fundamentalist conservatives were the only major demographic to experience a significant decline in their trust of science since 1970. This pattern relates heavily to the partisan, divisive rejection of climate science.

The Pew Research Center corroborates this relationship through a 2020 survey, finding that Republicans of every level of science knowledge were less likely than Democrats to acknowledge human-caused climate change. In fact, the most scientifically knowledgeable Republicans were less likely to recognize climate truths than less-educated party members.

Although further investigation is needed, these studies, taken together, indicate striking parallels between anti-intellectualism, climate policy, and conservatism that may explain a partisan pattern of climate change denial.

America’s pivotal role in climate change cannot be understated. As the nation with the largest consumer culture in the world, our every step threatens to tip the ecological balance.

Hofstadter’s anti-intellectualism explains the divisiveness and failures of the climate movement thus far. Confrontational partisanship and hyper-polarized attitudes dominate our political ideologies. Along with a societal emphasis on individualism and populist anti-elitism, these factors create a foundation for anti-intellectualism and the rejection of science.

This modern anti-intellectualism stalls climate reform legislation, benefiting corporations, lobbyists, and corrupt politicians. As the climate crisis continues to escalate while we fail to act, humanity has arrived at a precipice—decisive and immediate action, along with worldwide cooperation, is necessary to prevent catastrophic global collapse.