In 2010, Cargill, a US private multinational corporation, pledged a zero net deforestation goal in all production sites by 2020. Last year, the company announced it would not achieve this aim.

It wasn’t surprising.

In 2017, Cargill was “one of the two largest customers of industrial-scale deforestation” because of its soy production sites. Some of the company’s most destructive actions are in the Cerrado region of Brazil. Home to many indigenous tribes, the Cerrado is one of the largest, most biodiverse savannahs in the world and is the source of multiple tributaries of the Amazon River. By deforesting the Cerrado’s rainforests, Cargill has displaced indigenous groups, threatened ecosystems, and increased carbon emissions.

While Cargill promised to achieve zero net deforestation in its supply chain, the company assured Cerrado soy farmers that it would not support the moratorium on deforestation. According to Ruth Kimmelshue, head of Cargill’s supply chain, a soy moratorium would be ineffective because other companies would take Cargill’s place and buy crops from the deforested land. Instead, the corporation pledged $30 million for alternative methods to prevent deforestation in Brazil.

Neither Kimmelshue nor any other Cargill representative specified what these “alternative methods” would entail, simply stating that the sum would fund “new ideas for ending deforestation in Brazil.” This vague multi-million-dollar pledge was hardly consolation for environmental advocacy groups frustrated by Cargill’s lack of commitment.

National Wildlife Federation Director Nathalie Walker notes that “what was disappointing was that Cargill was lauded for its actions, and then didn’t follow through.” Cargill turning back on its promise, though gravely disheartening, is hardly shocking. Rolf Skar, Greenpeace USA’s assistant campaign director, remarked that its promise showed little planning from the start.

Cargill’s troubling history of environmental and human rights abuses illustrates a repetitive pattern of exploiting laborers and indigenous land to reap profits with little regard for environmental conservation. It also earned them the title “The Worst Company In The World” in a 2019 report by environmentalist group Mighty Earth.

Cargill’s Mounting Abuses

For years, Cargill deliberately funded farms that relied on child labor to depress the cost of cocoa. In 2006, six former slaves from Côte D’Ivoire filed a lawsuit against Nestlé and Cargill for the trauma they faced due to these exploitative practices. Unsurprisingly, Cargill denied these claims. In 2017, a Los Angeles district court dismissed the case, citing that the evidence did not illustrate US-based involvement in the alleged violations.

Later that year, the plaintiffs provided proof that US offices made payments to the cocoa farms using personal money. Based on these findings, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated the case and found for the plaintiffs. The court condemned Nestle and Cargill for their direct involvement in the child labor crisis in Côte D’Ivoire, which violates customary international human rights law.

Though the court ruled against Cargill, it did nothing to pressure the company into reassessing its supply chain. Cargill has denied its wrongdoing since, asserting that it would not “let these legal proceedings deter [it] from working actively every day to protect human rights.” In January 2016, Cargill requested the lawsuit be dismissed, but the Supreme Court promptly rejected its petition. But on July 2, 2020, the court agreed to hear the case, egged on by—no surprise—the Trump administration. In a brief this past May, the administration urged the court to rule that US corporations cannot be sued under US federal law for human rights violations abroad.

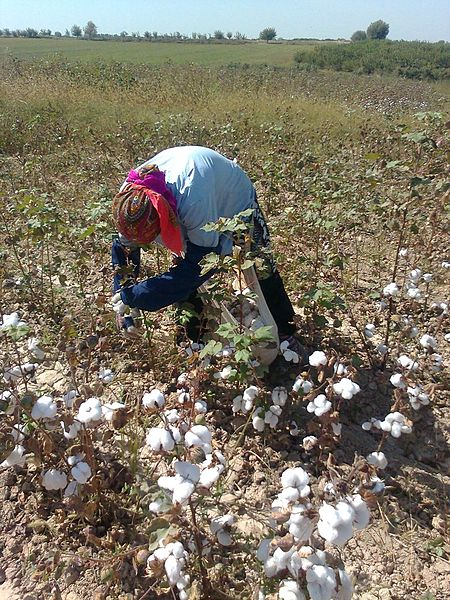

CargillCotton, a subsidiary of Cargill housed in Liverpool, faced a similar controversy by sourcing from Uzbekistan. The country’s cotton industry notoriously employs forced labor; in 2014, it coerced millions of people—doctors, nurses, teachers, and children alike—to leave their jobs to harvest cotton. Cotton profits flow to the Uzbek treasury, with very little (if any) going to workers.

In 2004, CargillCotton’s corporate citizenship report failed to consider its suppliers’ child labor policies. A spokesperson for Cargill claimed that if child labor exists in the supply chain, it’s because families need help managing the fields—a flimsy justification for a grave crisis.

By sourcing from Uzbek cotton, CargillCotton exacerbated Uzbekistan’s labor exploitation crisis. In 2010, The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) petitioned CargillCotton to change its practices, arguing that the company sourced products stemming from child labor. However, the company brushed off the center’s request, stating it would revisit the issue in a year. While the conglomerate did call for an international investigation, the suggestion proved meaningless. To this day, Uzbekistan denies the existence of forced labor in its industries and prohibits investigations.

After this petition failed, the EECHR joined a coalition of non-governmental organizations, business associations, trade unions, and investors to form the Cotton Campaign. This movement advocates for governments to use their leverage over Uzbekistan to end forced labor in the cotton industry.

After the United Kingdom passed the Modern Slavery Act in 2015, the campaign criticized its lack of effective regulatory measures. The bill only mandated that companies report how they combat forced labor, failing to establish formal review mechanisms to monitor these accounts. The campaign contends that this law is toothless, especially for companies like Cargill that aren’t consumer-facing.

The law did little to directly influence Cargill’s behavior, as the company had already started cutting Uzbekistan from its supply chain after mounting pressure from EECHR and the International Labor Rights Forum’s campaign. This may seem like a victory, but the company’s supply chain is still tainted with exploitative labor. Cargill noted in its 2017 Report on Forests that it trades in Zambia. However, the report omitted the gross human rights abuses that occur there.

While Zambia does prohibit forced labor, the government cannot enforce this law because it lacks the proper resources to investigate allegations. Ultimately, Cargill swapped one problematic source for another, doing little to address the Cotton Campaign’s root concern.

Cargill’s deliberate negligence of this issue within its supply chain is a testament to its prioritization of profit over scruples about such practices. The company’s global supply chain runs on unethical practices, yet it does nothing to reform its network. Thus, the issue lies in instilling a conscience into a corporation that has little regard for the atrocities it perpetuates.

The agribusiness giant has been equally destructive at home, where its corn and soybean production has heavily polluted the air and water. With lax federal legislation, particularly under the Trump administration, Cargill has even less incentive to become environmentally conscious.

In March 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency ruled that the Cargill-owned salt ponds in Redwood City, California would not be subject to the Clean Water Act. The CWA protects such areas by limiting pollution and making it unlawful to discharge pollutants that can be easily traced to one source, including discharge pipes, drainage ditches, and municipal wastewater treatment plants.

The Trump administration’s decision contradicts Redwood City’s regulations, which forbid development on the ponds. The regulations are integral to protecting these biodiverse salt ponds, which maintain the Bay Area climate, reduce smog, and prevent tidal flooding. These benefits—which only scratch the surface of the ponds’ utility—would cease to exist without CWA protection. The ruling grants Cargill free reign to build housing units and further develop the area. With even the US government remaining complicit, it seems like a far cry to pressure Cargill to act more conscientiously.

Adding to environmentalists’ grievances, in 2018 Cargill announced the construction of a meat processing facility in North Kingstown, Rhode Island in partnership with Ahold Delhaize. Ahold Delhaize is an international Dutch retailer that owns supermarket chains like Food Lion, Hannaford, and Stop & Shop. The retailer is a signatory to the The New York Declaration on Forests, a participant in the Protein Challenge 2040, and a party to the 2018 Statement of Support for the Cerrado Manifesto. These measures aim to combat deforestation, promote ethically sourced supply chains, and pressure other companies—including Cargill—to end deforestation in the Cerrado region.

Considering Ahold Delhaize’s fervent calls for sustainable food sources, it is disappointing to see the retailer provide Cargill business, as it paves the way for future wrongdoing. Every plant Cargill opens further diminishes its incentive to reassess its business practices. So long as Cargill is equipped with $100 million, state-of-the-art plants, convincing it to consider the ramifications of its practices is nothing short of a Herculean task.

Cargill claims that deforestation and exploitation will continue—even if the company changes its practices—because its competitors haven’t shifted their business practices. Such a statement is gross ignorance on Cargill’s part.

While Cargill does face intense international competition in the Cerrado region and a risk of upsetting the soy farmers with the moratorium, that doesn’t bind the company to continue deforesting lands. The company’s main competitors, Wilmar International, The Louis Dreyfus Company, and COFCO have announced they would no longer purchase soy from producers harming the environment. As environmental organizations have repeatedly urged, it is possible for Cargill to switch soy production onto already-cleared lands. Yet, the company continues to unsustainably source the soy that feeds its livestock, trailing far behind its forward-thinking competitors.

In the rare instances when Cargill inches towards sustainability, it moves only for money. In 2017, Cargill departed from its cattle-feeding operations to focus on meat-processing and diversify its protein-based business. By doing so, the conglomerate could hone in on higher-margin opportunities like aquaculture, plant-based protein, fish, and insects.

Cargill also wanted to capitalize off of rising consumer demand “for brands that are transparent in food marketing and ethical in their sourcing.” The 2015 Nielsen Global Corporate Sustainability Report found that nearly 73 percent of millennials would be willing to “pay more for products from companies committed to the principles underlying the good food movement.” It also found that sustainable companies grew four percent globally while their unsustainable counterparts grew less than one percent. In the following years, Nielsen found that sustainable companies had the “highest year-over-year sales growth.”

Following these market trends, Cargill invested in MemphisMeats, a Nashville-based company working to raise meat from animal cells. If successful, the product would help decrease—and perhaps even eliminate—the need for factory farming. Steve Myrick, Memphis Meats’ Vice President of Operations, notes that Cargill is “remarkable” in its ability “to feed countless millions of people.” His statement has two major takeaways. The first is that a corporation of Cargill’s stature can be a catalyst for good rather than destruction. The second is that Cargill’s economic interests must align with humanitarian interests for its business practices to change.

A Mighty Response

Mighty Earth labelled Cargill “The Worst Company in the World” because that’s what Cargill is. It’s an unchecked company that profits off of human rights abuses and environmental degradation. In the few instances when the company is challenged, it makes excuses and false promises.

American courts have failed to reign Cargill in, and federal law has failed to protect the environment. Cargill’s industry peers have done little to pressure the company to reconsider its actions. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has rolled back environmental regulations and repeatedly expressed support for developing the Cerrado forests further. But as Klara Skrivankova, co-founder of the UK Trafficking Law and Policy Forum, notes regarding the Uzbek cotton controversy, legal provisions—such as UK’s Modern Slavery Act—are not effective without consumers pushing for change. This is precisely the issue in countries like Zambia that, without effective regulatory tools, cannot hold Cargill accountable either.

That’s why it’s time consumers hit Cargill where it hurts: its wallet. Prefacing the 2019 Mighty Earth report, Chairman Henry Waxman writes, “under pressure, Cargill has reformed its practices in many areas—which shows that it can change when it wants to.” Cargill’s environmentally harmful actions are not because of an inability to be conscientious, but rather an indifference to act responsibly.

Shortly after the report’s release, Mighty Earth launched its multi-million dollar campaign to pressure Cargill and its customers to rid their supply chains of environmental and human rights abuses. Through this campaign, Mighty Earth calls on Cargill’s customers to stop remaining complicit. The campaign’s demand is simple: cut business ties with Cargill until the company reassesses its practices.

The campaign also seeks to connect to consumers at the grassroots level to educate them about where their food comes from. Once consumers are taught about Cargill’s environmental and human rights abuses, few would be able to, quite literally, stomach their food. To maximize outreach, Mighty Earth strategically focuses on one Cargill customer per region.

Mighty Earth Massachusetts’ campaign focuses on Stop & Shop (an Alhoid Delhaize subsidiary) since the company is based in Quincy, Massachusetts. The campaign has given concerned consumers the opportunity to engage in direct dialogue with Stop & Shop via phone call campaigns, social media outreach, and petitions to Stop & Shop CEO Gordon Reid in Massachusetts communities.

As a volunteer for Mighty Earth’s campaign, I have seen dedicated campaign organizers educating volunteers about its cause and the inner workings of a corporate campaign. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the campaign moved all events online. The campaign’s virtual platform extends far beyond Massachusetts, attracting volunteers from across the Northeast. Their combined efforts and commitment have not been in vain.

In recent Call-To-Action events this past May and June, I—alongside other volunteers—found Stop & Shop representatives to be receptive to consumer concerns, inquiring about the cause and willing to pass the campaign’s message to upper-level management. These actions have greatly helped to raise visibility for the issue among consumers and company officials. Stop & Shop has already taken to social media to respond directly to Mighty Earth’s complaints, evidence of the campaign’s growing momentum.

In a world where the ability to challenge the status quo seems out of reach, the Mighty Earth campaign gives people the chance to, literally, serve justice. We owe it to ourselves, those afflicted by Cargill, and future generations to voice our concerns when we have the chance.

For more information about the campaign against Cargill and how you can contribute, please visit Mighty Earth’s website or Mighty Earth Massachusetts’ Facebook and Instagram.