As the world combats COVID-19, China has been increasing its maritime activities in the East China Sea. On May 10, the Japanese foreign ministry lodged an official complaint with China over an incident where two Chinese ships chased a Japanese fishing boat close to the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands. A month later, four Chinese vessels, one carrying weapons, entered Japan’s contiguous zone (an area states establish dominion over) for the sixty-ninth consecutive day. These are Beijing’s latest provocations—which have become commonplace in the last few years—over the “disputed” islands.

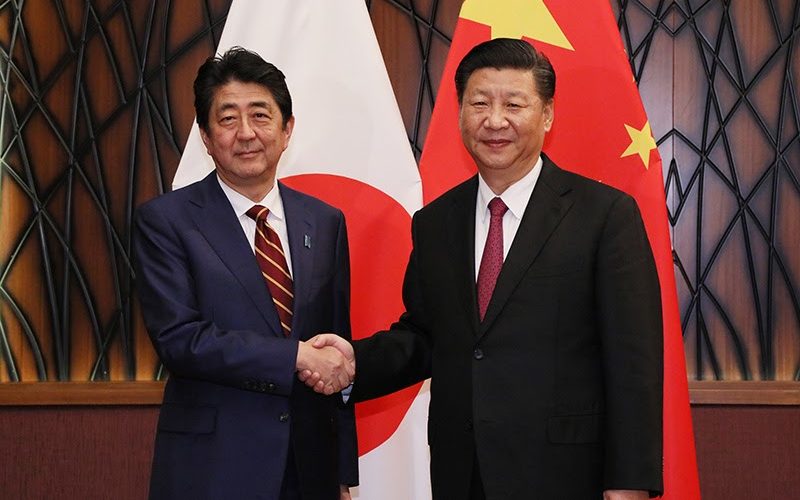

Before COVID-19, there were signs of a thaw in relations between the countries. In 2018, Premier Li Keqiang visited Japan, while Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited China. Both visits were the first of their kind in nearly a decade. President Xi Jinping was scheduled to visit Japan in April, but the trip was cancelled due to the pandemic. The trip would have been the first time a Chinese president visited Japan as a state guest in over a decade.

While the East China Sea issue has become an afterthought during the pandemic, it would be ideal to discuss a resolution now. With China facing increasing scrutiny for “mishandling” the outbreak, it may be more willing to concede to Japan in order to prevent further damage to its reputation. Additionally, China is eager to strengthen cooperation with Japan to revive its economy; continued provocation would threaten this goal.

This grants Japan more leeway in negotiations. For Tokyo, resolving this prolonged issue would end an issue of major public interest. Meanwhile, Beijing can prove its commitment to bilateral cooperation and restore prestige in the world—something Beijing covets to push forward other projects like the Belt and Road Initiative. A resolution would be a win-win.

Historical Disagreements

In 1895, Japan formally incorporated the Senkaku Islands—a group of eight islands, of which seven are state-owned—into Okinawa prefecture. Government documents declared the islands terra nullius, or uninhabited, a legal justification for administering unsettled lands. That April marked the end of the first Sino-Japanese war, culminating in China’s surrender and the Treaty of Shimonoseki. In the agreement, China did not cede the Senkaku Islands along with Taiwan and the Pescadores. This indicated to Japan that China did not consider the islands theirs to give. Thus, Japan continues to deny any dispute over them.

China disagrees. The Chinese government states that the islands were part of China since ancient times. However, international law stipulates that mere discovery is insufficient to acquire territory; continuous and peaceful display of sovereignty with the clear intention of possessing the territory is necessary. As such, China does not have the legal footing to assert that its sovereignty over the islands derives from ancient history.

For more contemporary evidence, China points to the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951, which transferred back to Beijing all the territories Japan had taken. Japan argues that the Senkakus were never part of the treaty (Article 2 returns only Taiwan and the Pescadores), and that the Chinese did not dispute sovereignty over the Senkakus at the time. Instead, Japan asserts they surrendered the islands to the United States after World War II and that the territory remained in America’s possession until the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement returned the islands to Japan.

After World War II, China did not challenge Japan’s sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands. In 1953, the Chinese Communist Party newspaper described the Ryukyu Islands (now known as Okinawa) as consisting of seven island groups, including the Senkakus.

China remained silent on the matter until the United Nations Commission for Asia and the Far East published a report in 1969 noting huge deposits of oil and hydrocarbons in the waters surrounding the Senkakus. The commission found that the continental shelf in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea might be among the richest oil reserves in the world. Following these findings, China and Taiwan declared sovereignty over the islands.

The US Energy Information Administration estimated that the region held enough oil and gas to power either Japan or China for the next fifty to eighty years. For China in particular, declining domestic production and increasing demand for oil make the prospect of a regular source especially enticing.

However, as prominent realist scholar Hans Morgenthau explains, “if sovereignty means supreme authority, it stands to reason that no two, or more, entities can be sovereign within the same time and space.” Under this principle, the country with the strongest claim—in this case, Japan—should exercise sovereignty. So why is China still questioning Japan’s administration of these islands?

One major reason is to save face. While China’s original motivations were economic, their aims have become more complex. China harbors deep suspicions toward Japan’s sincerity regarding its imperialist past and the atrocities it committed against China. Past polls indicate that 70 to 90 percent of Chinese hold negative views of Japan. Japan is viewed as an “enemy,” and any concession entails Chinese weakness. The Chinese leadership can’t afford to turn back now.

In addition, the region is strategically relevant. With control of these waters, China could place intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets to tap Japanese communications. This would be beneficial to China, especially considering Japan’s close relationship with the United States. Moreover, the waters around the Senkakus are one of the few routes that break through the first island chain, a region China must secure to defend its mainland against encirclement from the United States Navy. The waters lead straight through to Okinawa and the western Pacific, allowing Chinese vessels to circumvent other routes with American presence.

China’s Rapid Militarization

Against this backdrop, China has challenged Japanese claims to sovereignty for the last forty years, frequently entering Japan’s territorial waters without causing a direct confrontation. These intrusions remained relatively minor until 2010, when a collision between a Chinese fishing boat and Japanese Coast Guard (JCG) ship heightened tensions, as Japan threatened to prosecute the boat’s captain. Relations deteriorated further in 2012, when Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda decided that purchasing Uotsuri, Kitakojima, and Minamikojima Islands—privately owned by a Japanese person—would defuse tensions.

This act of nationalization angered China, breaking the existing balance and prompting aggressive behavior by Beijing. An official Chinese white paper published in 2012 asserted that China “exercised administration over Diaoyu Dao (Senkaku) and the adjacent waters.” A year later, China established an air defence identification zone (ADIZ) in the airspace around the islands, overlapping the ADIZ Japan established in 1969. An ADIZ is an airspace in which the declaring country identifies, locates, and controls aircraft in the name of national security.

A defiant Beijing also issued a statement warning that armed forces would adopt defensive emergency measures if foreign aircraft entered the zone. Experts believed China’s actions were a retaliatory move for the nationalization of the three islands. Fearing a loss of control over the islands, Tokyo expanded its own ADIZ.

Tensions were so high that, in 2013, Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd declared the conflict “the most worrying in contemporary Asia.” While Tokyo and Beijing’s relationship started to improve in 2018, rapid militarization of the region continues.

This game could quickly spiral into an international crisis if an accidental collision were to occur. In 2014, two People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Su-27 fighters came within thirty meters of a Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF) aircraft, raising concerns that it was only a matter of time before an accident occurred. With Chinese vessels and aircraft becoming ever larger and better-armed, the chances are greater than ever.

Xi asserted that China will “absolutely not give up [its] legitimate rights and interests.” As such, Chinese military modernization has accelerated in the past decade. The so-called gray-zone tactics (sub-threshold coercion) employed by the Chinese make it difficult for Japan to respond militarily. By using the paramilitary Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) instead of the PLA, China avoids directly provoking the JSDF. If Japan retaliates, China can play the victim and escalate things further, citing Japanese “aggression” towards the CCG.

China continues to argue that actions around the islands are not violations of foreign waters, but a legal exercise of national sovereignty. Between April and June of 2019, the CCG entered the contiguous zone sixty-four days in a row, then the longest recorded run of entry. In fact, last year saw the most entries into the zone in terms of days and number of vessels.

This was no fluke. Chinese navy vessels have steadily increased in number and variety. According to the Japanese Ministry of Defense, since 2015, vessels entering the contiguous zone carried weapons and were accompanied by intelligence-gathering vessels—something that had not happened in twelve years. Since 2014, vessels have also become larger, with three-thousand-ton or larger vessels frequently spotted. In conjunction with size, China proved its capability to introduce a large number of vessels in August 2016, when two-to-three-hundred fishing boats (some armed) entered the contiguous zone.

中国海警局は尖閣海域をよく航行させる海監3000トン型(11隻)とは別に漁政3000トン型を12隻建造してる。うち1隻は米バーソルフ級のようなステルスっぽい船型。こういうスピードで増強される組織の相手を海保はしなければならないわけで pic.twitter.com/M7fHOB8gcB

— ぱらみり(健全アカウント) (@paramilipic) March 21, 2016

Restructured operational forces have reinforced these improvements. China has strategically strengthened cooperation between the navy and the CCG. For instance, in July 2018, the CCG integrated into the People’s Armed Police, an organization under the command of the Central Military Commission led by Xi Jinping.

In the air, Chinese aircraft forced the Air Self-Defense Force (ASDF)—a division of the JSDF—to scramble (quickly mobilize aircraft) 851 times in 2016. The entry of aircraft such as Chengdu J-10 fighters and Xian H-6 bombers into Japan’s ADIZ indicates that China is stepping up its aerial presence. Unmanned aerial vehicles have been successfully flown around the Senkakus as well. Since May 2017, Chinese drones have improved their operational capabilities. This creates asymmetry in equipment and pressures Tokyo to take countermeasures, evident from the fact that a drone was able to fly in Japan’s ADIZ for several hours in 2018.

Japan’s Bolstered Defense

Japan is constrained by Article 9 of its Constitution, which renounces war, prohibits war potential, and denies rights of belligerency. Unless the Constitution is amended, Japan’s abilities remain limited.

The government attempted to circumvent these constraints by reinterpreting the Constitution via cabinet approval in July 2014. It aimed to broaden the JSDF’s mandate by arguing that the right to self-defense was guaranteed by the Constitution, evident by the creation of the JSDF in 1954. Therefore, Article 9 was interpreted as a constitutional right to possess the minimum armed forces necessary to exercise self-defense. Further, Abe’s cabinet argued that self-defense was necessary to uphold the Constitution’s preamble and Article 13, which protect citizens’ rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Under this interpretation, as long as enemy territory is not occupied, the JSDF can defend the homeland and support allies.

Naval defenses are mainly under the purview of the Japanese Coast Guard. To support its activities, the government has increased the JCG’s budget by 40 percent, added twenty-one patrol vessels, and increased personnel by 10 percent since 2012. To combat Chinese activities, a guard unit dedicated to patrolling waters around the Senkakus was also stationed in nearby Ishigaki Island (170 kilometers north).

The Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF)—a branch of the JSDF—acts if tensions escalate to the point the JCG can’t handle it. Here too, legal constraints are placed on weapons use. Article 7 of the Police Duties Execution Act allows JSDF personnel to use weapons for self-defense, while Article 16 of the Japan Coast Guard Act grants the authority to request inspection of vessels. Once foreign vessels enter Japan’s waters, the JSDF follows international law by requesting vessels to leave before employing force. In June 2016, a Chinese navy vessel entered Japan’s contiguous zone just outside its territorial waters. In response, an MSDF vessel repeatedly requested that the foreign vessel leave, and got the ship to retreat before serious action was taken.

Article 84 of the Self-Defense Force Act states that, unlike land and sea, air policing can only be done by the ASDF. The primary role of the ASDF is to scramble (quickly mobilize military aircraft) against intruding aircraft in observance of international law, as compliance allows Japan to justify its presence in the region. In fiscal year 2018, the ASDF scrambled 999 times, ninety-five times more than the previous year. This was the second highest number of scrambles since 1958. Shockingly (or not), the ASDF had scrambled against Chinese aircraft 638 times, approximately 69 percent of all responses that year.

Japan has also created specific measures for dealing with attacks on remote islands. The Japanese Ministry of Defense’s white paper clearly states that “should any part of the territory be occupied, the SDF will retake it by employing all necessary measures.” The first-ever special police unit—the 2,100-strong Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade—was created in March 2018 to respond to illegal landings.

To supplement this strategy, the JSDF acquired new destroyers and the E-2D airborne early warning aircraft to detect signs of attack. The Medium Term Defense Program for fiscal years 2019 to 2023 also plans to establish one airborne early warning wing, a squadron of unmanned aerial vehicles, and new air defense radars. To deal with short-range or mid-range ballistic missiles, the JSDF procured stand-off missiles capable of responding from outside the threat zone; furthermore, Japan started research and development on technologies required for anti-ship missiles and hyper velocity gliding projectiles—all of which China allegedly possesses.

Unlike China, Japan has physical limits to the number of forces at its disposal. This has led the JSDF to restructure units and move them southwest. Currently, there are several major units around the Senkaku islands, mainly housed in Okinawa. Of the group, the most noteworthy reformation was the ASDF establishing the 9th Air Wing in January 2016 and forming the Southwestern Air Defense Force (responsible for all air activities in the region) in July 2017. It was the first realignment of the ASDF since the Cold War.

4/All of this signals #Japan’s response to Chinese activity in & around the E China Sea—the biggest trouble spots for Japan being the Tokara Strait, the Miyako Strait, and the Senkakus. (Shown on the pic below👇)

Makes sense why Japan picked those places for new bases, eh? pic.twitter.com/aAlWb8nCd2

— Michael Bosack (@MikeBosack) March 17, 2019

Another significant move was the establishment of new bases on nearby islands to monitor the Miyako and Tokara straits. While not specific to the Senkakus, these bases serve as the “southwestern wall” to prevent Chinese action in the East China Sea. These military bases house 700–800 troops, anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries, and radar/intelligence gathering facilities.

Considering its legal and physical constraints, Japan’s response has been remarkable. However, a 2018 report by RAND suggested that it was unsustainable. Japan has already taken extraordinary measures, such as reorganizing defense structures, doubling the number of fighters, and increasing defense spending. China’s quantitative superiority—1700 fighters compared to Japan’s 288—could further pressure Japan’s already-stretched JSDF.

This quantitative gap becomes worrisome when considering the ASDF’s rotation policy, which is critical for maintenance. Currently, the ASDF rotates planes from other bases in the north while planes from the southern bases are out for maintenance on the mainland. At some point, Japan’s southernmost bases will have fewer aircraft to scramble Chinese aircraft.

China can also pressure Japan by increasing the number of patrols around the islands. China increased patrols around Taiwan from 1100 times in 1999 to 1700 times in 2005. Fighters flew around Taiwan an average six to twelve times per day, even reaching twenty-four flights at times. Since China only flies around the Senkakus three times on average, an escalation to these levels would overwhelm the ASDF. Additionally, increased scrambles mean less training for pilots, a point of concern for the ASDF.

3 Chinese coast guard ships patrolled on Chinese territorial waters around Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, Sun pic.twitter.com/CP2mhpZe6N

— People's Daily, China (@PDChina) April 25, 2016

Preventing Accidents

In 1972, the International Maritime Organization, the UN’s shipping regulator, enacted the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea. The Convention applied to all ships, not just navy vessels, and set the “rules of the road” to prevent collisions. It designates rules for speed, sailing in specific situations, and communications between ships.

But it didn’t specify how to handle the impending collision of armed navy vessels.

The lack of specific regulations regarding navy vessels led to the enactment of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) at the Western Pacific Naval Symposium in 2014. Japan, China, the United States, and eighteen other countries set forth a code of conduct for such encounters. While non-binding, China’s signing of a multilateral code of navigation was significant progress. The Code advises against several actions which may lead to serious ramifications, including “aiming guns, missiles, fire control radars, torpedo tubes or other weapons in the direction of vessels or aircraft encountered.” Using lasers—which China had before—is also discouraged.

A major step forward would be expanding the scope of CUES, applying it to coast guard ships and making it legally binding. Although stiff Chinese resistance is expected, Japan and other countries must persuade Beijing that freedom of navigation—as stipulated in Article 87 of the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea—is far more advantageous than a closed sea which would aggravate conflict.

Japan and China have several bilateral mechanisms in place to prevent collisions. However, considering the increasing number of Chinese intrusions, there may soon come a time when these mechanisms prove insufficient. This is because most mechanisms are subject to political tension and aren’t backed by concrete commitments.

The Japan–China Defense Ministerial Meeting is the highest-level exchange to discuss this issue. Positive byproducts of these meetings include officer and unit exchanges. Most recently, a field-grade officer exchange program was held in 2018 for the first time in six years, while April 2019 saw the first visit of Japanese destroyer “Suzutsuki” to China in seven-and-a-half years. On that visit, the MSDF Chief of Staff also attended a high-level symposium hosted by the Chinese government. Though these are welcome exchanges, the meetings only maintain the status quo and avoid discussing a permanent solution. In addition, these meetings are not consistent enough to prevent accidents.

The Maritime and Aerial Communication Mechanism is a 2018 memorandum designed to promote bilateral air and sea defense cooperation specifically regarding the islands. Both sides agreed to hold annual expert meetings and establish hotlines between the defense ministers. Although meetings occur more regularly than before, there is no binding agreement compelling both sides to meet when political tensions are high; such a provision would provide regular opportunities to defuse tensions. In addition, the lack of concrete policy emerging from these meetings is worrisome. To be truly effective, the two countries need to implement what they discuss.

The Three Roads Ahead

Considering all this, there are three options available. The easiest option would be to maintain the status quo. Although Japan faces budget constraints and could be overpowered by the CCG’s world-best tonnage and manpower, Tokyo could continue to rely on the JSDF and US support to defend the islands. Japan’s defense budget is roughly one-third of China’s, meaning even a massive increase would not match Beijing’s growth capabilities.

In this scenario, the double-edged sword Japan holds is the presence of the US. President Obama was the first president to state that the Japan–US Security Treaty applied to the islands. President Trump echoed Obama’s words in 2017 and assured that this would remain so. Article 5 of the treaty states that each party recognizes that an armed attack against either party in Japan’s territory would be met by proportional action. This is a powerful deterrent and a threat to China. The more the US asserts itself in the region around the Senkakus, the more it prevents China from engaging in a full-scale conflict; however, greater US involvement also provides China a reason to increase its presence and perhaps strike first.

The status quo is the result of incompatible positions hardening over time. Japan will continue to assert that no dispute exists, despite the ongoing violations by Chinese vessels that have become an eyesore and a threat. Under these circumstances, especially due to the higher chances of accidents, it becomes increasingly important for both sides to understand that the situation is unsustainable. While easy to maintain, the status quo is risky. Any number of factors could pull the three countries into a larger conflict.

A riskier move would entail Japan amending the Constitution and breaking with the tradition of spending less than one percent of their GDP on defense. In this scenario, Japan would risk a major conflict by giving China a reason to forcibly take the islands. While most of Abe’s conservative supporters want the constitutional reform, doing so would amount to political suicide at a time when cabinet approval ratings are dipping amid the pandemic. It would also break with the enormous restraint Abe has shown throughout the years, possibly endangering Japan’s tradition of preserving peace in the region. Nonetheless, it is an unlikely scenario considering the mixed support for amending the Constitution and the lower house election likely to be called before the four-year term expires in October 2021.

International arbitration could also cause China to escalate tensions in the region; after the Philippines took China to court over the Spratly Islands, Beijing responded with a series of naval exercises in the region. This could partially explain why Japan has never resorted to this option—along with arbitration’s ineffectiveness in deterring China, and Tokyo’s unwavering commitment to denying a dispute.

However, if China keeps violating territorial waters, Japan could take this option like the Philippines did in the South China Sea. One factor that is significantly different from the Philippines’ case would be the distrust towards China incited by the pandemic. Beijing may be forced to acknowledge a new ruling in order to prevent further embarrassment and a loss of partner countries for other projects. Nevertheless, retaliation remains likelier than acquiescence.

This leaves the last option: resolution. While continued coordination with allies may help Japan avert major crises with China, it is a temporary solution. For a permanent one, China must accept that Japan has a stronger legal claim to the islands. If Beijing wishes to continue contesting Japan’s claims, it should do so through arbitration.

China can only criticize what it sees as the western-led international system after properly engaging with international institutions. For now, it has become clear that using military force to try to extort concessions doesn’t exactly help that argument. With China vying for improved relations with Japan, it is ideal for Tokyo to push for a resolution.

The Senkaku disagreement could be used to show China’s commitment to peace and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific. Words mean little if actions don’t align. In 2015, the PLA’s deputy chief of staff claimed that China was “making positive contributions to peace and stability of the region.” It’s time for China to prove true to these words and take meaningful action.

A great starting point would be reviving the 1978 Sino-Japanese Peace and Friendship Treaty. In it, both sides agreed to settle all disputes by peaceful means and declared that neither would seek regional hegemony. Neither provision has been kept. Renewing this commitment and returning to it every year or so would help both sides understand the importance of coexistence in the region. Japan should also propose a new treaty which explicitly states that there will be no further disagreements over sovereignty. Japan should have greater latitude now than ever.

It would be in both countries’ interest to understand that compromise is necessary to coexist in a stable Asia-Pacific. Sovereignty is indivisible, but resources can be shared. While negotiating a treaty, both countries could strive for another agreement like the East China Sea Peace Initiative proposed by Taiwan in 2012. Although the inclusion of Taiwan would be politically challenging, Japan and China could create their own version and see if both sides can hold their end of the deal.

That said, the issue is likely to return to sovereignty. When the two countries sought to jointly develop the Shirakaba/Chunxiao oil and gas fields in 2008, the project failed due to disagreements over drilling boundaries. However, the success of Taiwan and Japan in signing a bilateral fisheries agreement in 2013 provides hope. As President Ma of Taiwan said at the time, it is vital to “replace confrontation with dialogue, shelve territorial disputes through negotiations . . . and engage in joint development of resources.”

In the past, anti-Japanese sentiment was so high in China that retreating from this issue would have constituted a weakness. However, a 2019 poll conducted in Japan and China shows that Chinese impressions of their Japanese counterparts are improving every year. Negative impressions, which were at their zenith immediately following the nationalization of three islands, are down from 93 percent to 53 percent. From this standpoint, it would be the most opportune moment for China to compromise.

This is a win-win deal that saves face for both sides. Compliance with a new agreement would prove Beijing’s trustworthiness, which has taken a hit in recent months. There is also one less issue to worry about, as China focuses on quelling domestic unrest, the controversial Hong Kong issue, and the possibility of another trade war with the US. For Japan, preventing the violation of territorial waters is a major win for Abe (or his successor) and would reinforce Japan’s status as an international broker of peace.

That said, China’s actions around the islands are difficult to legitimize and a new partnership will be a hard sell to Japanese citizens already doubtful of Beijing’s intentions. Japan must stay alert for any signs of escalation. The process is not straightforward and will be painstakingly difficult. There will be times when tensions rise so high that one side may contemplate suspending all diplomatic relations. Both sides must realize that it is beneficial to cooperate rather than remain at odds over historical disagreements. Each nation is a top trading partner to the other, and increasing economic cooperation through joint infrastructure projects could help defuse tensions and facilitate an environment of coexistence.

The relationship between the two countries is likely to change as a result of the pandemic. In an attempt to rely less on China, Japan is already moving to diversify its supply chain. This should not be taken as a political maneuver, though. It is an economic strategy aimed to ensure Japanese supply chains remain intact even in crisis. This, coupled with the indefinite postponement of Xi’s visit to Japan, could pressure China to concede more to remain on favorable terms with Tokyo.

The pandemic has provided an opportunity to create a new environment—both politically and economically—for both countries to coexist. The time is ripe for a breakthrough. Ultimately, it will come down to whether both countries can muster up enough political will and determination to see this through. As challenging as it sounds, it will be worth trying. The game of chicken must end before it’s too late.