American prisons are founded on punishment over rehabilitation and profit over humanity. They maintain slavery under the guise of criminalization. And they have only worsened over time. Our prison practices exploit, neglect, and kill incarcerated people.

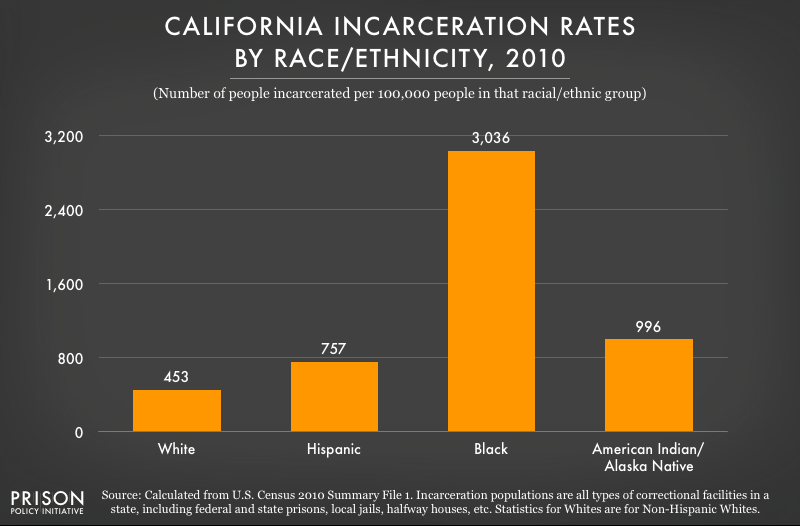

California’s incarceration rate alone is higher than the United Kingdom, Portugal, Canada, Belgium, and Italy combined. California’s prisons are severely overcrowded, at 137 percent capacity, with Black people, Native Americans, and Latinxs disproportionately incarcerated. In fact, Black people are incarcerated at a rate almost nine times higher than Whites in California.

These alarming numbers highlight the cruel, systemic racism the state continues to invest billions in. Inmates are stuffed into overcrowded dorm rooms and crammed into six-by-six-feet cells. They are treated as second-class citizens while prisons extract tremendous profits from their nearly free labor. If inmates are released, they receive no real support to help them successfully reintegrate back into our communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these cruel realities like never before, costing inmates their health and their lives. Thus far, California’s prison system has imposed limited, grossly inadequate measures. As of May 20, more than 3,200 inmates in California tested positive for COVID-19. If urgent action is not taken to improve policies and release more inmates, hundreds of thousands will remain at high risk for the virus.

During this pandemic, lawmakers and policy advocates have the opportunity to reform the discriminatory legislation that perpetuates such gross injustice. By examining how California’s prison system operated before and during the pandemic—specifically addressing overcrowding, labor exploitation, and the lack of release programs—we can offer policy proposals to reform and eventually dismantle it.

Overcrowding

Before COVID-19

Institutionalized racism in the criminal justice system predates the Civil War; however, the War on Drugs that began in the late 1960s significantly increased incarceration rates among minority populations and overcrowded our prisons.

President Reagan’s Anti-Drug Abuse Act established a hundred-to-one difference in the amount of crack cocaine versus powder cocaine needed to trigger a five-year federal mandatory minimum sentence. There were two main differences between these drugs. The first, a minute difference, was that crack cocaine consisted of powder cocaine and water or baking soda. The second, with severe implications, was the groups that used them. In Black neighborhoods, crack cocaine was more commonplace; in White ones, powder cocaine was. The law clearly targeted Black people, punishing them with harsher, longer sentences.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act is just one example of institutional racism in our criminal justice system. Currently, African American males make up 28.5 percent of California’s inmates, but only 5.6 percent of its adult male residents. Similarly, adult Latino males are imprisoned at roughly two-and-a-half times the rate of adult White males.

America’s overcrowded prisons fail to mirror the decline in violent crime rates seen over the past several decades, highlighting how grossly out of date sentencing policies are.

In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled that California’s overcrowded prisons and their conditions violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. However, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has balked in recent years at implementing a referendum, approved in 2016 by California voters, that would ease overcrowding by allowing nonviolent offenders to seek early parole.

Overcrowding seriously threatens inmates’ access to healthcare, food, and basic human needs. Where privacy is scarce, rates of self-harm, violence, and suicide increase. California’s inmate suicide rate is 80 percent higher than the national mean. One California inmate dies, on average, every six-to-seven days, because the CDCR unconstitutionally deprives inmates of adequate health care.

Fast forward to late January, when COVID-19 arrives in California. California’s prisons are 37 percent over capacity, just under the Supreme Court’s mandated limit. However, thirteen of the thirty-five state-owned facilities are over capacity; they hide it by housing over fifteen thousand inmates in camps or contracted facilities that the state does not own, where they are not counted. Thus, inmates have no chance of effectively implementing state-mandated physical distancing.

During COVID-19

During the outbreak, prisons across California have implemented new policies and physical distancing measures in hopes of controlling the spread of COVID-19. The new policies include eating in dorms and reducing the number of inmates during yard time. Some prisons are transferring inmates to vacant spaces, like gyms and houses, so they have more space. Sadly, overcrowding and limited testing make these measures ineffective.

These limited measures are nearly impossible to implement; inmates live in such close quarters, they share resources and rooms such as bathrooms and showers. Additionally, inmates face increased exposure risk from staff that contract the virus inside and outside the prison facilities. While prisons mandate that staff report any symptoms, this requirement is ineffective because many indicators of COVID-19 imitate the common cold. With limited testing, staff cannot ensure that they are negative before entering prisons.

Because of these inefficient policies, the number of inmates infected with COVID-19 increased sevenfold in just over a week; staff cases almost tripled. Furthermore, close to 5,600 of the 116,000 inmates in the CDRC are “65 or older, and 37 percent of the total prison population have at least one of the risk factors that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says put them at risk of severe illness from Covid-19.”

This is a significant proportion of vulnerable inmates. Yet staff do not have enough cleaning supplies to properly sanitize all prison surfaces and lack protective gear like masks or gloves. The measures, or lack thereof, are not protecting these inmates. Instead, these protocols and lackluster cleaning resources foster a breeding ground for COVID-19 and create a public health crisis for all inmates.

To make matters worse, prisons continue to deny the most vulnerable inmates their basic human rights. Inmates who have tested positive for COVID-19 are quarantined, but report not receiving enough food and water or adequate yard time; they are also unable to access doctors and basic medicine. Many inmates who show symptoms are quarantined in solitary confinement simply because there is nowhere else for prisons to put them.

In some prisons, inmates have been reprimanded for disinfecting areas with bleach and wearing face masks. Families of inmates have reported that they did not receive information from the prisons about COVID-19 measures. Prisons need to be held accountable; they need to stop treating inmates as second-class citizens, invest more in preventative measures, and operate with transparency.

Exploitative Practices in California Prisons

Before COVID-19

Overcrowding is not the only problem inmates face during this global pandemic. As many businesses and factories shut down indefinitely, private and public sector manufacturing turn to cheap prison labor to continue creating products.

As incarceration rates skyrocketed, so did the cost of running state prisons. To combat these expenses, California incorporated private businesses and created a profitable prison industry model: a prison–industrial complex. Under this model, states sign private prison contracts, green-lighting companies to use free or cheap labor in order to accrue vast profit margins.

After crime rates fell nationwide in the 1990s, California’s prison occupancy levels followed, impacting private profits. The leading private prison company’s stock dropped from roughly $150 a share to 19 cents a share, highlighting the connection between profits and prison populations.

Over four thousand companies have a financial stake in mass incarceration, and many rely on prison labor for their profits. Unicor, a government-owned corporation, implements prison labor programs across fifty factories. While touting goals of “reducing inmate idleness” and acquiring “marketable skills,” the corporation paid inmates between 23 cents and $1.15 per hour, significantly below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

This disregard for inmates’ financial security emphasizes retribution over rehabilitation and profit over humanity. Some prisons encourage inmates to work by offering reduced sentences to those that comply. This is modern slavery—the prison population is disproportionately made up of Black people who have fallen victim to a racially biased system still rooted in the discriminatory legislation of the War on Drugs.

The graph above shows the stark racial disparities in the demographic makeup of California’s prison system. Blacks are incarcerated at over four times the rate of Hispanices and over six times the rate of Whites.

In recent decades, the private sector has jumped at the opportunity to employ inmates, as these companies are not required to offer health insurance, minimum wage, or vacation or sick time to inmates. Prisons leverage their inmates to bring in revenue, partially because of how costly it is to keep these institutions operating—approximately $9.3 billion dollars annually.

The exorbitant expenditures have caused California and its local governments to shirk these responsibilities from one level of government to another. Initially, California was eager to establish prisons as a profitable enterprise based on prison labor. However, once profits evaporated and exposed the true cost of housing inmates, California funneled inmates to county jails to reduce costs. As California grapples with overcrowding, state and local prisons continue shifting prisoners back and forth to avoid costs.

One would think, due to these massive costs, the state government would support increasing release protocol. However, in the age of COVID-19, California’s release protocol is grossly underprepared to ensure the safety and health of inmates.

During COVID-19

Despite the pause on “non-essential” work to reduce the spread of COVID-19, some prisons continue to endanger and exploit their workforce during this pandemic. In New York, inmates are producing state-branded hand sanitizer, NYS Clean, for 60 to 75 cents an hour. Prisoners reported they were unable to punch their time cards to report their hours. In some cases, inmates “have worked double shifts, or have worked on the expectation of future pay.”

As a society, we are endangering inmates to produce essential sanitation products that will hopefully mitigate the spread of COVID-19 everywhere, except in the prisons where the product is mass-produced. These inmates are exploited, forced to work in dangerous conditions with extremely low salaries. Prisons are prioritizing profit over inmate health.

To make matters worse, prisons are like black boxes—there is little information regarding what goes on inside them. It is incredibly difficult to ascertain how prisons and their “essential workers” are operating in California during this pandemic, including whether they are facing the same problems as prisons and inmates in New York. The lack of information raises a serious issue, as prisons cannot be held accountable for labor exploitation if there is no public information about how they operate.

Release Systems in California Prisons

Before COVID-19

In most American prisons, released inmates are given “gate money,” funds intended to help them get back on their feet. However, California’s allowance, $200 per inmate, has not been updated since 1973, when $200 was worth roughly $1,200 in today’s money.

Furthermore, there is no other state-facilitated release infrastructure. Research indicates the first seventy-two hours after release are decisive in whether an inmate will recidivate. Ex-convicts are offered no assistance in acquiring housing or employment, two necessities for successful reintegration into the community.

The prison–industrial complex profits when there are more people behind bars, meaning it is profitable for a private or public prison contract’s bottom line if ex-convicts reoffend.

In fact, San Francisco Public Defender Mano Raju estimates that 20 to 30 percent of California’s jail population has nowhere to live outside of prison. Minority populations face higher rates of homelessness than Whites and make up a disproportionate share of our national homeless population. While African Americans make up 13 percent of the national population, they make up 40 percent of the homeless population. Hispanics are also overrepresented, making up 22 percent of the nation’s homeless despite only making up only 17 percent of the national population.

In order to reduce COVID-19 transmission, California’s residents must have a secure and safe space to shelter.

During COVID-19

In order to reduce overcrowding and COVID-19 contagion in prisons, California has implemented early release programs. Over the last few months, the state released 3,500 inmates. In order to be eligible for release, inmates must have sixty days or less on their sentence—those who were sentenced for violent or sex crimes are ineligible. As a result of these measures, the Los Angeles and Sacramento County jail populations decreased by 30 percent; Orange County’s jail population has decreased by almost 45 percent.

However, this early release plan is insufficient; it leaves approximately 115,000 inmates in danger, most housed in prisons operating over capacity. Many social justice advocates and lawyers have stressed the urgency to release more inmates in the wake of this pandemic. Michael Bien, a San Francisco attorney fighting to release more inmates, stated that “under these overcrowded situations, there’s simply no way to do social distancing, quarantining, isolation the way the rest of us are . . . ”

State lawyers argue that prisons have done enough to combat the COVID-19 crisis and do not need any more involvement from the state in private sector operations. This is an unacceptable response. We are in the midst of a major public health crisis; it is morally imperative that the California government steps in to ensure prisons protect inmates and workers’ lives. We must look beyond profit.

Many are worried that once inmates are released, they will have no place to go. In Los Angeles county, approximately 30 percent of former inmates are homeless, a common rate across the state. As a result, many ex-convicts will be forced to live on the street without access to hygiene products, making them as vulnerable—if not more so—to COVID-19 as they would be in prison.

In order to reduce homelessness among recently released inmates, nonprofits and faith-based organizations contract with county and sheriff departments to help inmates find housing and jobs. However, these organizations are under massive strain during this pandemic and lack enough funding to help ex-convicts.

The state is piloting a program to house the homeless and ex-convicts at risk of homelessness in hotels, granting them shelter and reducing their risk of contracting and spreading the virus. Although this is a step in the right direction, the program has made only a small dent in a massive problem. The state has only acquired 7,000 rooms to accomodate over 150,000 homeless people.

We are entering the worst economic crisis ever, with over 3.5 million Californians registering for unemployment due to the pandemic. Expediting the release of inmates will reduce prison overcrowding, but a long-term plan needs to be enacted immediately to ensure ex-convicts can properly reintegrate into society not only for their well-being, but also for the success of our communities. If California’s release protocols are not changed to comprehensively assist inmates in finding shelter and employment, ex-convicts will join another neglected community: the homeless.

Calls to Action

As states begin reopening, we must not sweep the problems of the prison system under the rug again. Instead, we must work with social justice organizations and governments across the country to ensure that human rights violations are swiftly eradicated.

The US prison system is rooted in racist policies and supports inmate recidivism in order to continue profiting off exploitative labor practices. It will be a long journey to create a criminal justice system that prioritizes rehabilitation and values human lives, particularly Black ones.

In order to protect the rights of convicts, reforms must be implemented with prison abolition as the long-term goal. Prisons can no longer act as opportunities for cheap labor and swallow countless nonviolent inmates in the name of justice. They create financial instability in local communities, break families apart, and keep countless citizens in poverty, all the while offering inmates and families no opportunity to heal. The policies listed below are the first steps towards prison abolition.

Reducing Overcrowding:

Overcrowding is not simply an issue of intake, although that is the largest contributor. It is also influenced by release eligibility. The following proposals, if enacted, would reduce prison populations.

To reduce jail and prison intake:

- Classify misdemeanor offenses that pose no public safety threat as non-jailable offenses.

-

- Since Black people are 2.8 to 5.5 times more likely than White people to be arrested on drug-related charges (despite using drugs at the same rate), reclassification of these offenses would decrease minority incarceration rates.

-

- Institute citations instead of arrest protocols for low-level crimes.

- Redirect those eligible in custody to mental health and substance abuse treatment programs and reallocate funds to psychiatric treatment centers in order to house sick inmates.

-

- California lacks sufficient beds and facilities to house the inmates in need of treatment. Nearly a third of inmates have a documented serious mental illness; the lack of available treatment centers has forced inmates to seek treatment behind bars to no avail.

-

- Abolish parole and probation revocations for technical violations.

-

- In 2016, sixty thousand people nationwide went back to state prison for violating the technical rules of their probation or parole, not for new offenses.

-

- Vacate bench warrants or unpaid court fines and fees for failure to appear in court.

-

- This is especially relevant during the pandemic, since it would allow indebted people to seek medical care without fearing arrest.

-

- Redirect state profits from mass incarceration to restorative justice programs that provide an alternative to serving jail time.

-

- Restorative justice aims to mend relationships through community support and inclusion. It focuses on healing and rehabilitation while taking into account race and class in mass incarceration.

-

To reduce overcrowding by reforming release protocol:

- Expand categories for release eligibility, specifically for non-violent offenses, thereby shortening their sentences.

- Expedite parole by instating partial clemency for soon-to-be-paroled inmates.

Reducing Labor Exploitation

Inmates are exploited by the state and private institutions that extract billions in profits from their labor, furthering the practice of punishment and profit over rehabilitation.

To protect inmates from labor exploitation:

- Abolish labor incentives linked to reducing and increasing sentences; implement protocols that ensure all inmate work is 100 percent voluntary.

- Require that contracts between state-owned prisons and state and private companies be performance-based, ensuring their practices reduce recidivism and promote rehabilitation.

-

- Performance-based contracts grant private prisons bonuses (some up to $2 billion annually by the state) if they reduce recidivism by predetermined quotas.

- These contracts also incentivize private companies to fund social justice programs in prisons—the company gets paid only if the program meets certain quotas. The lower the recidivism rate, the more interest a private company can accrue.

-

- Amend the Fair Labor Standards Act so it applies to inmates. This would increase wages for inmates to at least the state minimum wage and offer employer-paid health insurance, vacation, and sick time.

Increasing Release Eligibility and Support

Release protocols need to be reformed to reduce overcrowding and allow inmates to reintegrate into society. Even after inmates are released, there is minimal support to ensure their successful transition.

To increase support and services for ex-convicts:

- Amend policies so parolees are eligible for all government programs.

- Increase gate money, linking it to the Consumer Price Index to account for inflation.

- Redirect state profits from mass incarceration to nonprofits that support recently released inmates through reintegration programs, as well as to communities of color that have been disproportionately targeted by discriminatory legislation.

- Abolish voting eligibility requirements that prohibit parolees from voting.

-

- Giving parolees—a disproportionate number of whom are minorities—the right to vote gives them a say in how they’re treated.

-

Moving Forward

Amid the uncertainty and fear during this pandemic, we have been granted a unique opportunity. The impact of COVID-19 has shed a light on the stark disparities in our communities. It has exacerbated an already inhumane prison system that is designed to target and incarcerate people of color while extracting billions in profits.

California’s lack of urgency in releasing more inmates to reduce overcrowding and slow the spread of the virus in prisons shows how inmates’ health needs are not prioritized and that they are treated as second-class citizens. This pandemic has underscored how cruel and immoral our prison system truly is; it desperately needs to be dismantled so prisons can no longer prioritize profit and punishment over rehabilitation. The policies listed above are just the first steps towards transforming the prison system until new systems built on rehabilitation and equity can take its place.

If we have learned anything during this pandemic, it is how connected we all are. We must seize this opportunity to work together to reform, and eventually dismantle, the prison system in California and across our country. It is imperative we take actions beyond reforming prisons to create positive change for inmates and our communities. Mass incarceration is linked to other systems of institutionalized racism—such as policing, housing, education, healthcare, and finance—that harm and kill minorities, especially Black people.

To create sustainable change, more policies must be adopted in order to change the discriminatory laws and practices in each of these sectors. These reforms will not only improve the lives of people of color, but also everyone in our communities. As a result, we will become a stronger, safer, and more unified country.