The idea of a “rule-breaking” fourth term for the incumbent leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has been floating around for some time. Under party rules, the leader “may only serve up to three consecutive terms (nine years).” Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will reach that limit in September 2021, fueling rumors as to who will succeed him. While Abe himself admitted that a fourth term would be unlikely, several factors may push him toward launching another re-election campaign.

Why It Could Happen

The strongest case to be made for a fourth term is that there is precedent. During a March 2017 party convention, party members voted to allow their leader to run for three, instead of two, consecutive terms. The move came before the 2018 in-party leadership election, permitting Abe to run for a third term and become the longest-serving leader in party history. Following this pattern, the possibility of another amendment this year—before the 2021 election—should not be ruled out.

The idea of continuity in policy may elevate Abe for re-election. In his annual policy speech to the Diet in January, Abe outlined his administration’s policies for the year, the most contentious of which was amending Article 9 (renunciation of war) of the Constitution. Thought to be Abe’s primary policy goal, amending the Constitution has been hotly debated for the last couple of years, but has yet to be introduced as legislation.

Abe’s original goal was to form a resolution within the party, send it for a vote in the Diet, and then to a national referendum before 2021. This has proven difficult, so Abe only mentioned the Constitution at the very end of his speech, saying that it is “the responsibility of elected officials to decide what the future of Japan looks like [by discussing amendments].” Considering the time constraint Abe faces with his term limit and the determination he has shown to achieve this goal, a fourth term would provide a lifeline to pursue a referendum. Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso echoed this thought in an interview, stating that “with only two years left, if the PM [Abe] wants to seriously pursue this, he must be prepared to run for a fourth term.”

Abe has nine years of experience (2006–2007 and 2012–present) running the party. Over those nine years, the LDP has won all five national elections, underscoring Abe’s leadership and ability to win. As is the case in many other countries, political parties tend to choose a leader who is most likely to deliver electoral victory. In that sense, there is no one better suited for that role.

Abe’s margins of victory have also been impressive. The LDP currently holds 58 percent of the seats in the Diet; since its inception in 1955, the party has held 40 to 65 percent of the seats.

The Role of Factions

In addition to his electoral record, Abe is a master party organizer. Since its inception, the LDP has been organized as a coalition of informal factions (habatsu). The LDP originates from the conservative political parties in post-war Japan and has seen a constant restructuring of party factions, typically along policy lines.

Japan’s spectrum of “left” and “right” is complex and different from American politics. In general terms, the conservative right values economic growth and supports constitutional amendments and traditional family structure (e.g. wife takes her husband’s last name). The liberal left takes the opposite position and works to reduce inequality. Unlike the US where the left–right divide is obvious, the conservative LDP has introduced legislation to increase the minimum wage and provide free early childhood education, something the left would usually propose. In that sense, there is general confusion as to who supports what policy even within the party. This is where factions come in.

A unique characteristic of such factions is their leaders’ immense power over group members. These leaders tend to be powerful figures in the party politicking to become—or compromise with—the party leader, who would become Prime Minister should the party gain a lower-house majority. As a result, the power of each faction (the number of members) is considered when appointing the nineteen cabinet officials. Factions also support candidates and incumbents during elections by providing financial assistance and manpower. This consensus-building support structure has long been a tradition and continues today.

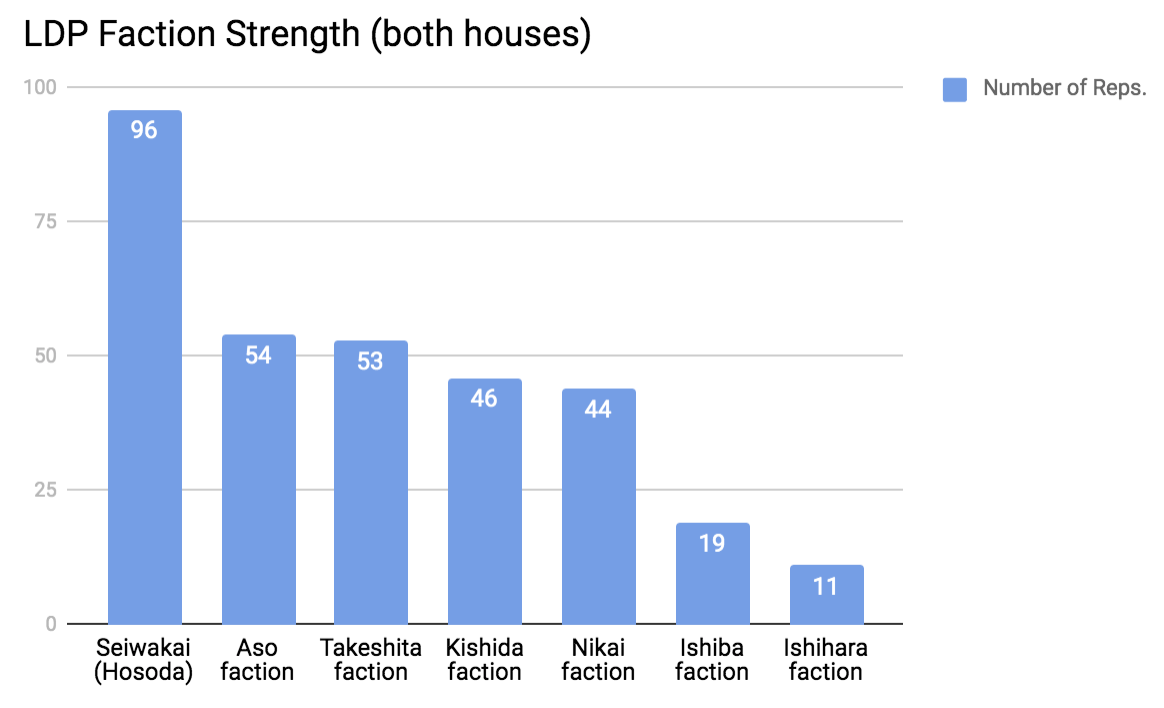

While there was a period (2001–2006) when then-leader Junichiro Koizumi attempted to purge such traditions to win over independent voters, Abe has since reverted to the traditional system of consensus-building. Currently, there are seven factions within the party; Abe’s (Seiwakai) has the most members (ninety-six as of 2019). The second-largest one has just fifty-four members.

Since the early 1980s, independents—those unaffiliated with any faction—have risen within the party. As of the most recent election in the summer of 2019, there are more than fifty unaffiliated politicians, making it the second largest “faction” in the party. The reason for such change has been twofold. First is the decline in funds available to each faction. In the early 1980s, each candidate received the equivalent of approximately ten million dollars to run an election campaign. Now they get just one million, making it unattractive to be restricted by factions both agenda-wise and financially.

Another reason is the change in electoral systems. In 1994, Japan adopted a single-member district (SMD) system with plurality voting and a party-list system with proportional representation. This was a significant transition from the single non-transferable vote system of multi-member districts. Under the new system, parties did not have to send multiple candidates into one district. One candidate could be selected per district, diminishing the need for support from strong factions. The party’s sole control over which candidates are recognized has severely damaged the control of factions over election outcomes.

Abe has used this consensus system to allocate top cabinet positions to each faction, including the independents, six of whom were named cabinet ministers in the latest reshuffle. This has kept many on board with Abe, preventing any revolt from fellow party members. Abe learned from his predecessors that alienating traditional blocs would only lead to trouble; former leader Koizumi had to send competing candidates to SMDs whose politicians openly opposed him. To move his agenda smoothly, Abe has elected to work with the factions, checking and managing the party’s historically complicated system.

Singular popularity within the party could persuade Abe to stay on for three more years. While Abe has remained publicly non-committal, faction leaders including former Prime Minister Taro Aso and Secretary General Toshihiro Nikai have both voiced their support for a fourth term. According to a December 2019 poll of LDP supporters, Abe had more than a 15 percent lead over other choices. Since Japan’s prime minister is the majority party’s leader, member voices matter.

The 2021 Leadership Election

The next party leadership election is slated for September 2021, where a total of 810 votes will be contested. The LDP’s system splits these 810 votes into two: 405 to LDP Diet members and 405 to the 1.04 million party members (i.e. the ‘local’ vote). Abe has a stronghold over Diet members through the consensus-building mechanism and relative popularity among party members. This was proven in the last party election in 2018, when Abe beat Shigeru Ishiba 553–254. Specifically, Abe had 82 percent of the Diet member votes and 55 percent of the local vote. This election exemplified Abe’s electoral strengths and widespread support among party members.

However, these numbers could overstate Abe’s strength. In a separate poll conducted last month, 20 percent of respondents cited the “lack of alternatives” as the deciding factor for their support towards the LDP. This is true both inside and outside the party. Within the LDP, no major opponent has threatened Abe as the face of the party. Building up to 2018, Shigeru Ishiba, the former secretary general of the party (runs the day-to-day operations) had formally challenged what he called “Abe dominance” in the party. Although he fell short, Ishiba used his status as former Minister for Overcoming Population Decline and Vitalizing Local Economy and almost surpassed Abe’s campaign in local votes.

This loss isolated Ishiba within the party, further alienating the Diet member vote he would need to defeat Abe in the future. Still, in a January poll, Ishiba was placed first, ahead of Abe by six percentage points, as the person voters wanted to see as the next prime minister.

Other notable candidates have suffered in national polls. Fumio Kishida, Abe’s “preferred successor” according to some media, polled at three percent in the same poll. Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s son and current environment minister Shinjiro Koizumi polled above Kishida, but at six percent. While Ishiba was placed first among all candidates, 24 percent of respondents chose nobody. This worrying lack of popular leadership choices could both help and hinder Abe’s chances at a fourth term. Due to the lack of quality candidates, other members of the party leadership (Aso, Nikai, etc.) may ask Abe to run again. However, if a charismatic candidate entered the race, things could change very quickly.

Outside the party, the numbers show a similar pattern. Party approval ratings in recent months show the LDP with a sizable lead over opposition parties. The LDP has consistently gained at least 20 percent of overall support, compared to 5.6 percent for the largest opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan. Again, more than 60 percent of respondents chose “no party.” This alarming number shows how the LDP continues to retain its majority status, as well as why this lead is not as solid as it seems. In the meantime, though, the LDP stronghold is unlikely to change.

The Downsides of Abe Seeking a Fourth Term

All signs seem to point toward a fourth term. However, not all is well for Abe and his administration. Approval ratings for the Abe cabinet in February show higher unfavorability (39.8 percent) than favorability (38.6 percent) for the first time in a year and a half. This was a direct result of the separate ministerial scandals involving the Minister of Justice and Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry, as well as the cherry blossom scandal involving the prime minister allegedly rewarding his supporters with invitations to a publicly funded event. Both cabinet ministers violated the Public Office Elections Act; one gave gifts to constituents in exchange for support while another gave gifts and paid campaign staffers more than what was permitted by law.

Yet scandals are nothing new. In 2016 and 2017, Abe was involved in a series of scandals involving favoritism toward a friend and to a school where his wife was scheduled to be named the honorary principal. In these cases, opposition parties called for Abe to resign, only for his favorability to rise. Part of the reason for the uptick was Abe’s base being riled up by the “unfair treatment” he received in the Diet, and the voters feeling time was wasted on the scandal rather than on other legislative issues.

Unlike in 2017, though, the number of scandals being uncovered simultaneously and the cabinet’s lackluster explanations—especially regarding documents from the cherry blossom event that were unlawfully shredded—have hurt favorability. In addition, the now-resigned ministers have refused to relinquish their positions in the Diet, further casting doubt on whether they regret their actions.

Without a serious challenger, the LDP has relaxed oversight over its politicians. The lack of clear explanations to the voters also shows that the cabinet feels no need to clear up anything with the public. This starts at the top with Abe, meaning a change in leadership may be necessary to provide transparency and clarity. While this has not immediately blown up the cabinet, boiling frustrations of the people may call into question the LDP reign.

Are the Tides Turning Against the LDP?

Evidence of such frustrations can be seen in the results of the 2019 upper house elections. Despite the LDP retaining simple majority control, the coalition supporting amendments to the Constitution did not reach the necessary two-thirds majority. Furthermore, the four main opposition parties—Constitutional Democrats, National Democrats, Social Democrats, Japanese Communist Party—continued to work together to defeat the LDP, supporting a single candidate in all of the thirty-two single-seat districts. The LDP retained twenty-two of the seats, but the opposition won some heavily contested districts, proving further cooperation could set up serious competition in the future.

Still, without an integration of policy, cooperation has its limits. A recent merger of the Constitutional Democratic Party and the National Democratic Party broke down due to the disparity in power the merger would produce. If the opposition cannot compromise on small things like the name of the new party (which was actually one of the reasons merger talks dissolved), how can they prove to voters that they are a viable alternative? They need to win a majority before bickering about policy differences.

In addition to the slow “rise” of the opposition, the LDP’s traditional voting base is slowly shrinking, which could further chip away at the LDP majority in the next election. In the past, the LDP has turned to farming, construction, and other industries that have always voted with them. Due to the shrinking rural population, among other reasons, these base groups have gradually declined in numbers, causing a real sense of crisis for future elections. This was partially why former PM Koizumi elected to reject their support and tried to attract the mostly urban independent vote. In the 2019 election, combined votes from the agriculture and construction interest groups, the two largest in the LDP, decreased by at least eighty thousand since the last election in 2016, and the trend is likely to continue.

Revitalizing the Party

Similar to the issue of accountability, trust in politicians is low, especially among younger generations. Chief among the reasons for this is the feeling that their voices are not heard by the politicians in the Diet. In several recent surveys, voters aged 18–34 tend to see politicians as working for their own profit. Younger voters tend to view their vote as worthless and unable to change results. This stems from periodic scandals and the general sense that one vote rarely impacts election outcomes.

Abe could step down to usher in a new age of younger politicians at the forefront of the party. Creating a new image could be crucial in winning over independent voters. Abe made a move in that direction in the last cabinet reshuffle by including the aforementioned Shinjiro Koizumi, a popular thirty-eight-year-old politician, as Minister of Environment. Koizumi became the third-youngest minister in the post-World War II era and is seen as a future prime minister. This, among other reforms, may improve the party’s standing with the people and win them new supporters.

If Abe does not seek reelection, he could step back into a vital role in the party and push forward with the creation of a party suitable to attract younger voters. For this to happen, the party should immediately find viable replacements for top officials—namely Aso (seventy-nine years old) and Nikai (eighty-one)—with officials who represent the younger generation. Also, to be more representative, all political parties should consider in-party rules restricting older politicians from seeking reelection after a certain age. In the 2019 election, the oldest candidate elected to office was a seventy-eight-year-old LDP candidate. Abe could think in a futuristic sense and give way to a younger leader while working behind the scenes to revitalize the party.

A holistic view of the process to determine the next leader of the LDP and the country produces several conclusions. First, it would be no surprise if Abe runs for another term to achieve policy goals, but also due to the lack of alternatives. Abe is a successful leader who wins elections and can manage the politicians in the party. The prime minister has the blessing of other top party politicians, fueling the rumors of a fourth term.

On the other hand, recent cabinet scandals may have begun a trend of anti-government sentiment. Another scandal or mishandling of responses to the media may increase support for opposition parties. The ongoing spread of coronavirus following the decision to allow people to leave the quarantined Princess Diamond ship could also cause problems. The latest poll conducted on February 22 and 23 showed that unfavorability ratings had spiked by 7.8 percent to 46.7 percent, while favorability fell below the average the LDP has maintained since 1955.

Furthermore, if the opposition unites in the next snap election, rumored to be after the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Abe may be forced to step down before considering a fourth term. In the long-term, Abe could also elect to cement his status by supporting his successor in restructuring the party.

Without a strong leader at the helm, Japan’s future is in doubt. As the majority party holding the highest office in the land, the LDP must continue the search for a successor even if Abe decides to run for a fourth term, while also working to rebuild trust with the people. At the same time, a strong opposition is necessary to keep the government in check. Keep a close eye on Japanese politics this year.