On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) a pandemic. Since the outbreak began in December 2019 in China’s Wuhan city, the number of reported cases has increased daily, so it’s no wonder that people are bombarded with news about it every day. While recent news about COVID-19’s mortality rate and containment methods are critical, not all news coverage of the outbreak has been equal. A number of stories, especially early reports, have ranged from thoughtless at best to downright racist at worst. Misinformation about the virus continues to rapidly spread through various social media platforms. This combination of misinformation, fear, and racism has negatively affected East Asians around the world, regardless of their affiliation with China or the virus.

Media coverage sets the stage for public debate, and media companies determine what’s newsworthy, essentially telling people what to think about. The more a topic is covered in the news, the more importance people place on the issue. That’s why news companies must be diligent in considering how they cover COVID-19.

The United Kingdom’s Daily Mail and The Sun have published multiple articles expressing disgust toward eating bats and other animals, insinuating that Chinese people are to blame for the outbreak because of their eating habits and culture. Never mind that the widely circulated video of bat soup was taken out of context, and that bats are consumed in many parts of the world, including Africa and Oceania.

France’s Le Courrier Picard published articles with inflammatory headlines such as “New Yellow Peril?” and “Yellow Alert,” referring to the racist anti-Asian ideology that has plagued Western society since the nineteenth century. News sources, particularly tabloid newspapers, often use fear-inducing language such as “deadly disease” and “killer virus” that only exacerbates the problem.

Even more traditional sources such as The New York Times and CNN have published thoughtless articles. Most articles focus on the number of deaths in outbreaks, but fail to note the number of recoveries; skimming through news articles, one would think that COVID-19 was a death sentence instead of a recoverable illness. People are usually drawn to alarming stories, and more views means more profit. However, the focus on death instead of prevention and recovery means that most people are more fearful of coronavirus than they probably should be.

Most notably, when reports of COVID-19 first came out, many articles referred to it as the “Wuhan coronavirus.” Such a label is problematic. Although people in China refer to it as the “Wuhan coronavirus,” and that may be why Western media began doing so as well, that is no excuse for journalists to ignore the consequences of their choices. Referring to, and thus naming diseases after people, regions, or animals can harm communities by stigmatizing them and prompting racist treatment. In the case of COVID-19, it already has.

Spotted this on my way back to home#coronaravirus #كورونا #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus pic.twitter.com/85pSHyjQIQ

— protagoras (@Protagos01) January 29, 2020

People of East Asian descent around the world have reported verbal and physical harassment and racist treatment. Many businesses have put up signs banning Chinese customers. Hundreds of thousands in South Korea and Malaysia have signed petitions asking the government to ban Chinese people from entering their countries, and one petition from parents in the York Region of Ontario demanded that students remain home for at least seventeen days after returning from China. A woman in New York City was called a “diseased bitch” and physically assaulted because she was Asian and wearing a face mask. French Asians have experienced so much harassment that they’re using #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus (I am not a virus) on social media to complain of abuse. Even elite academic institutions have perpetuated the normalization of racism; the University of California, Berkeley recently removed a post—after much backlash—that claimed racism and xenophobia were “normal” reactions to the outbreak.

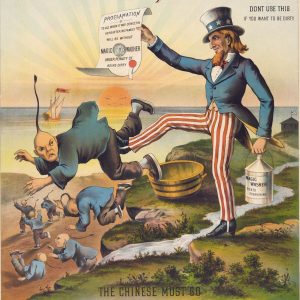

The outbreak has reawakened anti-Asian, specifically anti-Chinese, sentiment with deep roots in yellow peril ideology. The West has a history of viewing Chinese people and their customs as dangerous, dirty, and unwelcome. When Chinese laborers immigrated to the US during the California Gold Rush, white laborers felt that their jobs and opportunities were being taken away by immigrants. The idea that “immigrants are stealing jobs” persists today, evident from the ascendancy of Donald Trump, who commonly uses rhetoric such as, “They’re taking our jobs. They’re taking our manufacturing jobs. They’re taking our money. They’re killing us.”

Back then, white laborers and unions lobbied to keep Chinese laborers out of the US. Their biggest argument was that Chinese people carried “Chinese” forms of diseases, particularly sexually transmitted diseases, that were more virulent than “white” forms of diseases.

In particular, Chinese prostitutes were targeted. The Medico-Literary Journal of San Francisco ran an article in 1878 titled, “How the Chinese Women Are Infusing a Poison into the Anglo-Saxon Blood,” which stated: “If the future historian should ever be called upon to write the Conquest of America by the Chinese Government, his opening chapter will be an account of the first batch of Chinese courtesans and the stream of deadly disease that followed.” A member of the San Francisco Board of Health, Dr. Hugh H. Toland, believed that Chinese prostitutes had more virulent forms of STDs, particularly syphilis. People believed that leprosy was a “Chinese disease” resulting from generations of syphilis. They believed that “Chinese smallpox” was more contagious than “white smallpox.”

The editor of the Medico-Literary Journal was Mary P. Sawtelle, a suffragist and one of the first women on the West Coast to attend medical school. Dr. Toland founded a medical school that ultimately became the University of California, San Francisco. These were reputable people of their time.

Anti-Chinese sentiment was so strong that in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the US. Chinese food became a particularly specific form of American racism.

Ching chong Chinaman eat dead rats

Chew them up like gingersnaps!

This popular schoolyard chant stuck around for decades and was even performed by Judy Garland in the 1944 musical Meet Me in St. Louis. It seems, then, that major events such as COVID-19 can revert—or perhaps reveal—people back to xenophobic tropes. The stereotype that Chinese people eat “filthy, strange meats” still haunts Chinese people today, and recent coverage of and reactions to the outbreak confirms just that.

Food is fundamentally culturally relative, and Western disgust toward “weird” Chinese food is eurocentric. Never mind that Americans are eating more pork than ever despite the swine flu outbreak in 2009. Those who shame Chinese people for their food and customs fail to realize the bigger issue: that the Chinese government has struggled to properly regulate the trade of wild animals thought to be the root cause of the virus.

Coverage of virus outbreaks has harmed minority groups before. When AIDS was first discovered in the US in the 1970s, the government and mainstream news outlets ignored it because its earliest manifestations predominantly affected injection drug users and gay men. In fact, Ronald Reagan’s press secretary laughed about the AIDS epidemic with a journalist, calling AIDS the “gay plague.” These incorrect assumptions increased homophobia in the US following the epidemic.

When Ebola broke out in Africa in 2014, it was immediately associated with black people, regardless of their affiliation with Africa. Once again, people blamed it on “strange, African” food and customs, as if Africa is homogeneous and those who were infected were to blame for their suffering. Navarro College in Texas sent out rejection letters to Nigerian students, telling the students that the college would not accept students from countries with “confirmed Ebola cases,” even though Nigeria had successfully contained Ebola cases and days later was declared Ebola-free by the WHO. At a Pennsylvania high school football game, the opposing team chanted “Ebola!” at a black football player. Newsweek published a magazine cover with a picture of a chimpanzee and the headline, “A Back Door for Ebola: Smuggled Bushmeat Could Spark a US Epidemic.”

The list goes on. Misinformation about COVID-19 seems to be more contagious than the virus itself: Coronavirus can be prevented by taking Vitamin C and avoiding spicy foods; it can be cured by drinking a bleach solution. It originated from Chinese people eating cooked bats. Chinese spies smuggled the virus out of Canada; it was lab-engineered as a bioweapon.

Tech companies have a responsibility to mitigate the damage spread on their platforms. Companies such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google have long struggled to reduce the amount of health misinformation circulating on such platforms. Anti-vaccine posts and videos thrive on Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram, while bogus health advice flourishes on Twitter during viral outbreaks. In the wake of the most recent outbreak, Google-owned YouTube has seen multiple videos containing dubious information on the origins and spread of COVID-19 despite YouTube’s claims that its algorithm prioritizes credible sources.

Regarding COVID-19, Facebook claimed that it has labeled inaccurate posts and “lowered their rank in users’ daily feeds,” though notably, it has not removed posts containing health misinformation. While Facebook’s third-party fact checkers have rated certain posts as false, it’s particularly hard to control closed, private Facebook groups. Twitter has stated that it will expand a feature that places “authoritative health info from the right sources up top” when people search for a hashtag. And yet, misinformation thrives because once it has spread, it is difficult to control. That’s why it’s so important that anyone who uses social media recognizes their responsibility to mitigate the spread as well.

When a health crisis happens, people immediately want to know the latest information—even if it’s inaccurate. Those on social media who claim to know remedies and causes of health scares get the most attention even if they’re wrong. The temptation of identifying an easy cause and solution is too much for people to ignore, and while bots and human “troll farms” originate most misinformation, ordinary people pass it to their friends and family. People might not believe a piece of information shared by a random social media account, but are more likely to believe it if someone they know and trust shares that information.

So what can people do about all this? For starters, recognize that just because information is new doesn’t mean it’s accurate. Refer to and share sources that have an established track record of accurate science and health reporting; sources such as the WHO or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are more reliable than unknown personal social media accounts. Peer-reviewed medical journals have better information than a random post on Facebook, though even such journals have published false information in the rush to get news out. Lastly, people can check to see that the source is actually what it claims to be, as bots and trolls can invent government agencies or organizations to spread disinformation.

The media can also help prevent misinformation and fear from spreading. The pressure for media companies to put out breaking news is high. But in times of crisis, companies should pause and ensure all the information they put out is accurate before articles are published. Media companies should also take note of the words used and the tone of the articles; fear can be a social emotion, so companies must be careful not to sound overly alarmist and unnecessarily spread panic.

Social media companies should also be mindful of what is promoted on their platforms. Companies such as Facebook have already employed fact-checkers, who have found multiple fake posts regarding COVID-19 and have labeled the inaccuracies as such. While employing fact-checkers is important and necessary, social media companies should also provide accurate information alongside content with fake information so that people are exposed to correct information.

It’s not just misinformation that people need to be aware of. People must also consider the roots of their prejudice and selective empathy. When someone sees a comment like “We should just ban all Chinese from America,” they need to stop and think: does that commenter actually want to do anything helpful about COVID-19 or does the commenter just want to spread hate and fear? When someone says “Chinese people eat weird food and that’s why we have a new plague,” is that coming from a place of science or bigotry? Are people conflating the Chinese government, whose actions they may or may not agree with, with Chinese people?

It is far too easy in times of crisis to shun the other, blame the perceived outsiders, and ignore the humanity of those suffering the most. But it is also during these times that people, more than ever, must show compassion for one another.