From the heart

It’s a start, a work of art

To revolutionize make a change nothing’s strange

People, people we are the same.

Public Enemy, “Fight the Power,” Fear of a Black Planet (1990)

When people first heard those lines from the unparalleled baritone of Chuck D., the frontman for the hip-hop group Public Enemy, it was in Do the Right Thing, the 1989 Spike Lee joint that focused on racism, racial tensions, and the resulting violence in 1980s Brooklyn.

Even though hip-hop was born in New York and most, if not all, of the famous artists are American, it has become a transnational phenomenon. Musical groups around the world have adopted elements of hip-hop, identifying with marginalized voices everywhere.

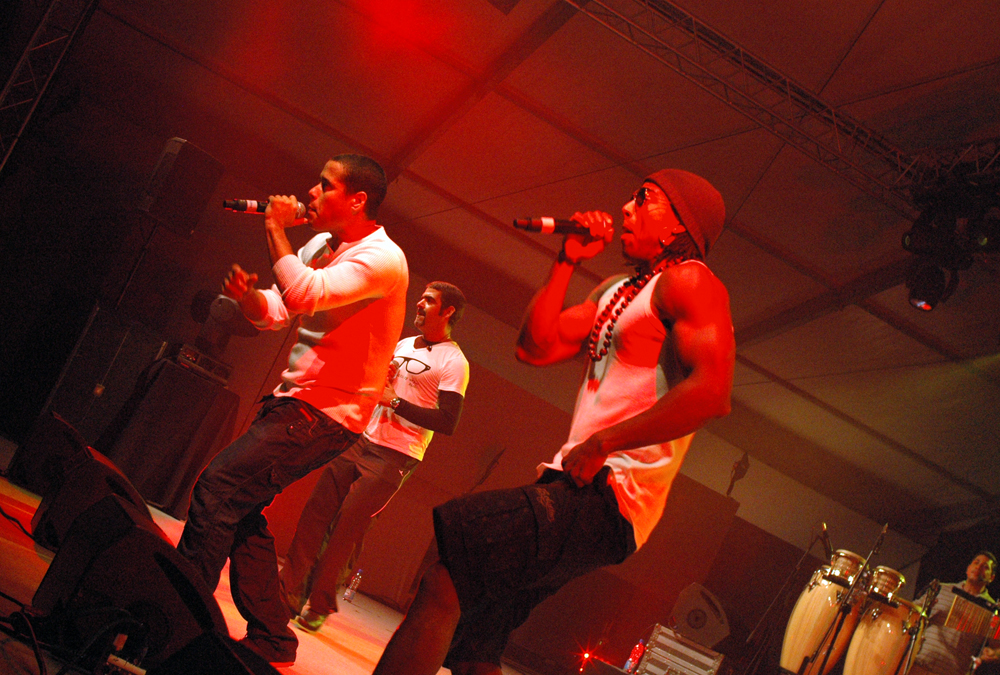

Public Enemy in concert. Left, Flava Flav, right, Chuck D. Hamburg, Germany.

Public Enemy is one of many hip-hop groups that used music as a cultural critique. Even if they wanted only to be artists, they became voices of the people—willingly or unwillingly—by elevating popular causes and voices through their music.

One of the most recognizable rap songs from that era was also one of the most incendiary: N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police.” It was a target of suppression from the FBI and local police on the grounds of “inciting violence,” and the FBI banned the group from performing the song during their first tour—a clear violation of the artists’ First Amendment rights. A letter written by the assistant director of the FBI Office of Public Affairs referenced police deaths in the line of duty, but failed to link N.W.A’s music to any fomentation of violence.

In Straight Outta Compton, the biographical drama about N.W.A, when asked why and how they could say such things about police officers, primary lyricist Ice Cube simply responded, “Our art is a reflection of our reality.” Growing up as young black men in Compton, California, they dealt not with a police force focused on community protection, but with a racist, corrupt, quasi-military organization that targeted black and brown minorities.

Fuck the police

Coming straight from the underground

A young n***a got it bad ’cause I’m brown

And not the other color so police think

They have the authority to kill a minority

Fuck that shit, ’cause I ain’t the one

For a punk motherfucker with a badge and a gun

To be beating on, and thrown in jail

We could go toe to toe in the middle of a cell

Fucking with me ’cause I’m a teenager

With a little bit of gold and a pager

Searching my car, looking for the product

Thinking every n***a is selling narcotics.

N.W.A, “Fuck tha Police,” Straight Outta Compton (1988)

Breaking down the allegations in the lyrics, a listener hears accusations of:

- Racial profiling: “A young n***a got it bad ’cause I’m brown”

- Police violence: “They have the authority to kill a minority”

- Profiling based on relative wealth and age: “Fucking with me ’cause I’m a teenager, with a little bit of gold and a pager”

- More racial profiling: “Thinking every n***a is selling narcotics”

Although N.W.A was protested by police across America and many other public interest groups, the group’s allegations have since been widely corroborated. Furthermore, some of these issues are only now being recognized on a greater scale. Today, Black Lives Matter is protesting the exact same phenomena: police violence and racism.

While it originally may have seemed like these tracks and the genre would cater to demographics that experienced the same social reality as the artists, hip-hop quickly spread to white America. Indeed, “many suburban white youth embrace and embody elements of hip-hop culture in their daily talk, dress, and musical listening preferences.” This, according to critical race theory scholar Kafi Kumasi, “is indicative of the ubiquitous and powerful influence of urban youth culture” on youth culture and society in general.

Songs like Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message”—one of the original hip-hop songs—and Wu-Tang Clan’s top single “C.R.E.A.M.”—which stands for “cash rules everything around me”—illustrate the harsh life of growing up in the inner city.

Broken glass everywhere

People pissing on the stairs, you know they just don’t care

I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious 5, “The Message,” The Message (1982)

Cash rules everything around me . . .

I grew up on the crime side, the New York Times side

Stayin’ alive was no jive

Had secondhands, Mom’s bounced on old man

Wu-Tang Clan, “C.R.E.A.M.,” Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (1993)

These songs describing life in New York City—respectively, the South Bronx in the seventies and eighties and Staten Island in the eighties and nineties—are often the first prolonged experiences the broader American population had with this specific segment of society.

Tracks with great lyrics, rhythm, and beats are made every year, but what makes many of the greatest hip-hop songs great, what gives them staying power, is a lasting message, whether it’s about love, loss, or (a critique of) society that resonates with listeners. Even more so when it comes attached to a memorable line like “fight the power,” “fuck tha police,” or “cash rules everything around me.”

An association with urban America has created a perception that hip-hop is uniquely American, or, at a minimum, created an overly (or exclusively) domestic catalog. International artists are presenting listeners with all the elements that Americans love in their own hip-hop, but they are not receiving remotely the same notoriety. Other recent genres of popular music have not been so domestic. Rock and roll, another genre influenced by Black America, was hugely popular in the United Kingdom, among other countries. Pop, a nebulous genre, has many popular Latin influences, and a handful of non-English songs have topped the Billboard 100 list, including Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee’s “Despacito” and Los Lobos’ version of “La Bamba.”

Discounting Canadian rappers—who share significant cultural influences with their American counterparts—like Drake or Kardinal Offishall, most Americans can barely identify a single international hip-hop artist or group. The most famous, the Fugees, has two Haitian members, but the frontwoman and most famous member is Lauryn Hill of the decidedly uninternational East Orange, New Jersey.

As an art form, hip-hop’s capacity to support protest messages of younger generations is transnational. Thriving hip-hop cultures exist across the world, with beats and rhymes and a unique, personal message that can still resonate culturally in the United States. Hip-hop is performed by Native Americans, French and French Africans, Basques in Northern Spain, and in the slums of Brazil, among other places.

French hip-hop group Sexion d’Assaut.

Take Cuba, a country cut off from the United States and most of the world due to its clash with the West over communism. Despite government policing of art, Cuba still has a vibrant and active Afro-Cuban hip-hop community, which emerged within and beneath the Communist regime. The song “Havana Side Underground” takes its title from a term describing the other side of life in Cuba. For Afro-Cubans this means lived experiences of anti-black racism and few means of advancement, an issue largely ignored by the government.

“Tengo,” meaning “I have,” is one of the most popular tracks from the Cuban hip-hop group Hermanos de Causa (Brothers of the Cause). Adapted from the poetry of Nicolás Guillén, a famous Afro-Cuban poet, the song angrily discusses their struggles as black people living under communism:

“Tengo una raza oscura y discriminada . . .

Tengo una jornada que me exige y no da nada

Tengo tantas cosas que no puedo ni tocarlas

Tengo instalaciones que no puedo ni pisarlas

Tengo libertad entre un paréntesis de hierro

“I have a dark and discriminated race . . .

I have a day that demands me and gives nothing

I have so many things that I can’t even touch them

I have facilities that I cannot even step in

I have freedom in an iron bracket

The first line talks about racism. The next accuses the communist government of unfair compensation. The rest focus on rights that cannot be realized: freedom in an iron bracket, freedom by name only, constrained by the shackles of dictatorship. The Cuban government has tried to solve and hide the issue by supporting artistic expression to a degree, but has censored meaningful public discourse and initiatives. Overt criticism of the government, and of the racism embedded in society, is reminiscent of the rhymes of Public Enemy and N.W.A thirteen hundred miles north.

Beyond the similarities, new forms of hip-hop that evolved in geographically unique locations allow for new innovations in the genre. In their song “Kirino Con Su Tres,” another Guillén adaptation, the Afro-Cuban feminist hip-hop trio Instinto rap over salsa beats instead of drum beats, a refreshing, fast-paced style. “Kirino” is a man’s name. In the poem he is described as “nappy-haired,” along with other pejorative stereotypes. A “tres” is a three-course guitar-like instrument popular in Cuba.

Cuban hip-hop group Orishas performing live.

Instinto turns the poem on its head by focusing on Kirino’s mother, who Guillén mentions only in passing, making her the focus of the track. Instinto offers a black feminist perspective, the latter of which is often missing from the genre. Although slightly better now, hip-hop was generally ignorant and often misogynistic when the song was released in 2004.

Mexico’s hip-hop sound is vastly different from Cuba’s. Due to its proximity to California, Mexican rap has a lot of similarities with its Angeleno counterpart. Fans of the gangsta rap genre—which includes N.W.A, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, and Ice-T—will hear similarities when listening to many Mexican acts.

Some groups, such as Cypress Hill, blend the two languages, releasing tracks in English, Spanish, and a mezcla (mix) of the two. In the track “Armada Latina,” frontman B-Real—along with featured bilingual Latin American artists Pitbull and Marc Anthony—lead off with their roots and ties to the motherland: “Came out the other man, southern land.”

Emphasis on roots is a consistent feature of Mexican hip-hop, more specifically, the national symbols and ancient peoples of the country. Kinto Sol offer an example in “Hecho en Mexico” (Made in Mexico), the titular track from their 2003 album:

También soy bravo como el licor

Verde, blanco y rojo

Ese es mi color

No tengo dinero pero me sobra el valor

Por mucho que se encuentre siempre traigo el calor

No olvido mi raíz, soy hijo del maiz

Orgulloso yo me siento de este gran país . . .

I’m also brave/rough like liquor

Green, white and red

This is my color

I don’t have money but I have the courage

For whatever is found I will always bring the heat

I won’t forget my race, I am a child of maize

I feel pride for this great country . . .

This verse addresses the colors of the modern Mexican flag and pride in socioeconomic class and race. It then references corn, a national symbol and the base of historical and contemporary Mexican diets. Later in the song, they proclaim, “Soy Azteca, Chichimeca, Zapoteca, Indio, Yaqui, Tarasco y Maya,” referencing the seven indigenous Mexican nations from which nearly all modern Mexicans descend.

Rap in Mexico can take on an anti-neoliberalism approach, a protest of the way the traditional order has impacted Mexico and the condition of marginalized Mexicans, who live with elevated levels of poverty, unemployment, and crime. The negative circumstances created a reactionary idealized view of the past in which genetically modified American corn has not yet supplanted Mexican farmers and where indigenous cultures have not been marginalized by neoliberalism and societal stratification.

This phenomena includes the group Sociedad Café—which roughly translates to “society of people with coffee colored skin“—who rap about race and skin color:

Café es la sociedad que vengo y represento

Café es el color que llevo muy adentro

Somos herederos de cultura pura, sabia, envidiable and enviable

Raza criolla hecha de bronce, respetable

Piel morena con orgullo represento

a los cuatro vientos, expresando lo que llevo adentro

Brown is the society that I represent

Brown is the color that I carry deep inside

We are inheritants of a pure, wise, culture

Creole race made of bronze, respectable

I represent Dark skin with pride

To the four winds, expressing what I carry inside

Sociedad Café “Sociedad Café,” Emergiendo (1999)

Many lyrics contain an interesting juxtaposition—Mexican pride and societal critique, a constant tension for Mexican artists. Yet, this is truly a definition of protest: willingness to criticize to improve something you love and to embrace risk to improve life for your community.

Cuban and Mexican hip-hop offer a new avenue to experience and learn about the underground culture, wrapped in a new package that might be more appealing than older forms of media. Novels and poetry are important and have their audiences, but so does hip-hop, and important truths should reach as many minds as possible. Diversity of medium is important, and the material is increasingly accessible through the internet and the spread of the language. More and more American students are learning Spanish, and for those who cannot understand, translations are available.

Students of politics, history, and many other disciplines are instructed to investigate primary material, and music is one way to experience it. Hip-hop offers a societal critique from the youth beyond America. Tunisian rappers made their voices heard during the Arab Spring, as did Egyptians (who sampled the aforementioned Lauryn Hill), Libyans, and other protesters.

Across the world, people are using hip-hop as an outlet. As the largest consumers of the genre, Americans have a unique ability to elevate voices, and to learn about struggles and protests across the world—often referencing the United States’ own legacy of revolutionary struggle.

Listen. Listen because it’s good music, a genre that feels familiar, but with a new pace, and a new language. Listen to learn.