Humanity’s propensity for unbridled technological advancement has pushed us ever closer to the edge of a cliff. The industrial revolution riddled us with greenhouse gas emissions, and the Manhattan Project brought us to the brink of nuclear devastation more than once. Our powerful painkillers—once touted as a cure for debilitating chronic pain—are now one of the leading public health issues in America. As we debate solutions to these political, environmental and health problems, one crisis lurks beneath the surface: antibiotic resistance.

The twentieth century was a golden age of infection treatment. It began in 1928, with the discovery of penicillin, the first commercialized antibiotic. The start of the modern era of vaccination followed, with the introduction of a state-sponsored polio vaccine in 1960. Life expectancy exploded from 57 years in 1928 to 76.7 in 1998. The role of antibiotics in this trend cannot be overstated. We could treat diseases and avoid complications in operations that previously led to infections.

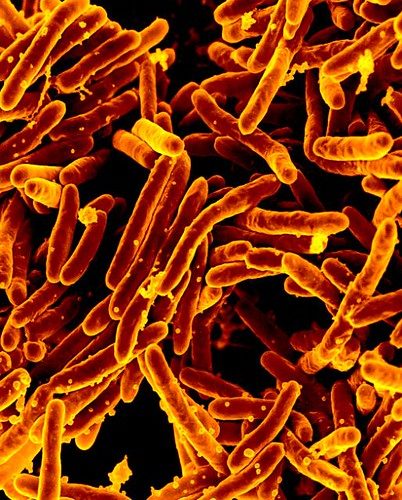

Unfortunately, this powerful medical landscape is slowly coming apart, and we are hearing almost nothing about it from our political leaders. There is the occasional headline or magazine cover with a menacing image of a bacterium, but this issue is still so underreported that these articles resonate only with those unfortunate enough to know someone affected by it.

Antibiotics are a class of compounds prescribed and administered to treat bacterial infections. They are typically prescribed in one of three circumstances. First, as a precautionary measure—surgical patients are often given antibiotics for potential infections. Second, as narrow-spectrum antibiotics—they are used as a specific treatment for a confirmed diagnosis, like strep throat or a sinus infection. Third, as broad-spectrum antibiotics—they are prescribed for infections of a basic or unknown kind in the hope that the infection is susceptible to one of those broad applications.

Antibiotic resistance refers to bacteria developing immunity to these drugs. In any infection, a bacterium may have a gene that makes it resistant or invulnerable to an antibiotic. When an antibiotic is administered, it kills all of the bacteria except the resistant one, which can then reproduce and become the dominant strain in the infection. In severe cases, when this gene has propagated, the infection is untreatable. Antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections are then treated with stronger and stronger antibiotics, and at each treatment along the way there is a risk of developing resistance.

There are two main concerns surrounding antibiotic resistance. The first is treatment-specific resistance. Tuberculosis (TB), for example, is a bacterial infection that requires a specific regimen of antibiotics. In certain parts of the world, TB has begun to develop a resistance to common treatments like rifampin. This new resistant strain—called “rifampin-resistant tuberculosis”—can no longer be treated with rifampin, leading physicians to prescribe a different series of medications to cure the infection.

This leads to the second concern: the development of a totally resistant bacteria, commonly known as a superbug. There are worries that such a strain of tuberculosis is propagating in India. The existence of this strain, and the use of the terminology, are still under review by the World Health Organization (WHO). In cases of totally resistant infections, physicians are left with no treatment options to cure a patient. With diseases as serious as TB, this is catastrophic.

As researchers begin to deal with this issue, the medical community appears to be its own worst enemy. While the senior community members, like experts at the WHO, appear to understand the gravity of this threat, medical professionals continue to overprescribe antibiotics in preventive and treatment approaches, mostly for respiratory conditions caused by viruses. According to the Centers for Disease Control, one in three antibiotics prescriptions are unnecessary. Physicians and other primary care providers (including physician’s assistants and nurses) must do more to ensure that prescriptions are necessary and patients are using them correctly. Forty-five percent of Americans do not take their full dose of antibiotics, often stopping when their symptoms subside.

It is no surprise that this issue is falling by the wayside. Drug resistance, like climate change, is abstract. While we are seeing some of its effects now, we won’t see its worst effects for years. Superbug infections killed 700,000 people last year. In 2050, the United Nations predicts that this number could be ten million, which—according to the WHO—will match the number of cancer deaths in 2018.

While this problem hides from most of our daily lives, physicians and nurses in hospital settings battle it constantly. Dr. Robert G. Sturgeon, a board certified doctor of internal medicine at the University of Utah Hospital, described the issue as one “that impacts patient care on a daily basis.” Hospitals, their ethics committees, and their infectious disease doctors have to decide whether a patient should be prescribed powerful antibiotics after weaker or broad-spectrum ones fail. Dr. Sturgeon has “seen infectious disease doctors refuse to approve the use of an antibiotic after physicians in the intensive care unit requested it.” In the end, the infectious disease doctor’s confidence in the diagnosis and the patient’s survival probability and potential quality of life can mean the difference between prescribing a powerful antibiotic or continuing to guard it from developing resistance. While still obscure in pediatric offices and walk-in clinics, the crisis exists in every hospital in the world.

The lack of antibiotic development—mainly propagated by market failure—is driving the crisis. Antibiotic drug development is difficult and expensive. After the discovery of penicillin, researchers kept finding organisms with antibacterial properties and developing them into drugs. Since then, it has become increasingly difficult for researchers to discover new organisms. Researchers have to either travel the world to find obscure organisms or synthesize new compounds in the lab. Even when a compound or organism is discovered, it can take hundreds of millions of dollars and up to ten years of research and development before the drug is eligible for approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

The other aspect of this market failure is that antibiotics are not profitable drugs. They are often short-term treatments, meaning that unless drug companies charge exorbitant prices they can’t make a serious profit. Because many of these prescriptions are for non-life-threatening infections, the companies can’t charge high rates; patients would just refuse the treatment. Antibiotics also have short lifetimes, as resistance begins to develop from the first clinical trial, so even if a company creates a profitable drug, it could become useless within years.

The future for antibiotics is complicated. For now, some companies will continue to develop new drugs or improve existing ones. In hospitals, infectious disease doctors are exploring the other side of infection treatment: the host. Some researchers believe host-focused care to be the best response to drug resistance. A vaccine is an example of host-focused medicine. Instead of introducing a compound to act on an infection, a vaccine arms the body with the tools to recognize and battle an infection on its own. Researchers are exploring the use of antibodies and lysins, which involve arming the host immune system with antibacterial tools. This approach could have much more staying power than an antibiotic, but the challenge will be how to effectively expand supportive care beyond vaccination.

Today, America’s health care conversation focuses almost entirely on coverage. This is an extremely important issue, but coverage will not matter if we run out of drugs to treat the most routine infections. Political candidates need to integrate this into their platforms in tandem with their health care bills or their labor reforms. Regulators need to either create incentives for pharmaceutical companies to develop these drugs or establish agencies dedicated to antibiotic drug discovery. Medical schools are already adjusting curriculums around opioid prescriptions, but now must ensure that antibiotic training is looked at just as critically. Hospital ethics committees must establish clear protocols and processes for the use of the most powerful antibiotic drugs, ensuring that we do not compromise patient care beyond what is necessary for our survival.

Federal and corporate institutions continue to fail to meet the demands of today’s issues, meaning that the role of the individual has never been greater. Many Americans can take a more active role in their health care, and much of this can be done in tandem with their health care professionals. Those who struggle with chronic illnesses or poverty should not have to bear this burden; Americans with broad access to health care must take action.

When you are prescribed antibiotics, ask your doctor to fully explain how to use them most effectively. Typically, this includes taking your entire prescription at consistent times. Patients can also try to confirm the necessity of an antibiotic prescription in the first place. This is something I began doing after I was on broad-spectrum antibiotics six times within eight months in 2017—at least two those instances now appear to have been unnecessary. Even things as simple as washing your hands more often will help fight drug resistance, as this will help prevent the development of diseases. If you use antibacterial soap, make sure these products primarily use alcohol or acid to kill the germs to further prevent bacterial resistance.

Americans are beginning to rise to the occasion on the world’s most important issues. Environmentalism, health care, and most other progressive political movements are growing. It is time that antibiotic resistance stepped into the spotlight, either on its own or tied to other health care or wellness platforms. If Democrats want to solidify themselves as the party of science, this is another issue to lead with. This could be one of the flagship issues of a 2020 presidential campaign. Hopefully, one of the candidates will take up that mantle.

This is the first installment in my column covering science, technology, and their connections to public policy. Problems like antibiotic resistance have the potential to destabilize societies, but are not given the necessary mainstream airtime. The column will focus on issues that are not widely discussed, or on specific, under-appreciated aspects of popular crises.