As the year 2000 drew to a close, two presidential candidates fought vehemently to claim the most powerful position in the world. Democratic candidate Al Gore called for a manual recount in Florida, where Republican candidate George W. Bush led by 0.5% in the initial tally.[1] They battled over how the votes should be recounted, which ones should be recounted, and who should count them. Eventually, after an unprecedented intervention by the United States Supreme Court, Bush claimed the election over Gore by just 537 votes.[2]

And all of this took place a state representing just 5% of the U.S. population.

The Electoral College—the mechanism that prompted the fiasco—is an inheritance from founding statesmen wary of the popular will. It’s undemocratic, complicated, and outdated. It’s also fixable.

The Electoral College remains in spite of public opinion, which indicates that two-thirds of Americans support electing the president via popular vote.[3] A majority consensus has existed around the popular vote for some time; 55% even support amending the Constitution to achieve this goal.[4]

But this problem has an easier solution: the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC).[5]

The compact was first proposed in 2006.[6] In 2007, Maryland became the first state to sign on, and the compact gained at least one new signatory each year until 2014. The group pushing the legislation is National Popular Vote Inc., a non-profit corporation led by professors, lawyers, businessmen, politicians, and other political figures.[7]

When a state joins the NPVIC—that is, the state legislature passes it and governor signs it—they are pledging to cast the state’s electoral votes for the winner of the national popular vote. The compact takes effect when states representing a majority of the country’s electoral votes (at least 270) sign on. Once the minimum number of electoral votes is reached, it won’t matter whether the remaining states join; the popular vote winner will always have enough electoral votes to claim the presidency.

Article II, Section I of the Constitution empowers state legislatures to select their electors as they see fit.[8] Whether the NPVIC will be ruled unconstitutional as a violation of Article I, Section X’s prohibition of agreements and compacts between states—as some have argued—remains to be seen.[9][10] But it shouldn’t be.

In 1892’s McPherson v. Blacker, the Supreme Court ruled that state legislatures “have exclusive power to direct the manner in which the electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed” and that the Constitution does not mandate the electors be chosen in a particular way.[11] The following year, in 1893’s Virginia v. Tennessee, the Court noted that Congressional approval is required only when the interstate compact increases state power at the federal government’s expense.[12] Under the NPVIC, the states wouldn’t usurp federal power; the compact is state legislation that replaces state laws.

The compact can remedy many deficiencies in our presidential elections, beginning with the notion of basic fairness. California, the nation’s most populous state, has one elector for every 712,000 residents. Wyoming, the nation’s least populous state, has one elector for every 192,000 residents. California has 55 electoral votes; Wyoming has three.[13]

But this is true only because a state’s number of electoral votes is equal to its combined number of senators and representatives in Congress. Because each state is guaranteed two senators and one representative regardless of population, each state must have at least three electoral votes.

The upshot is that a Wyomingite’s vote is worth 3.7 times more than a Californian’s. For the citizens of these two states to have equal presidential voting power, California would have to have 65 electoral votes, not 55. Wyoming, instead of three, would have one.

Compare any large state with a small state and you’ll find similar power disparities. Considering registered voters as a percentage of each state’s population, as well as the percentage of registered voters that actually vote in a given election, does impact some of the comparisons. But the larger point stands: how much your vote matters depends on where you live.

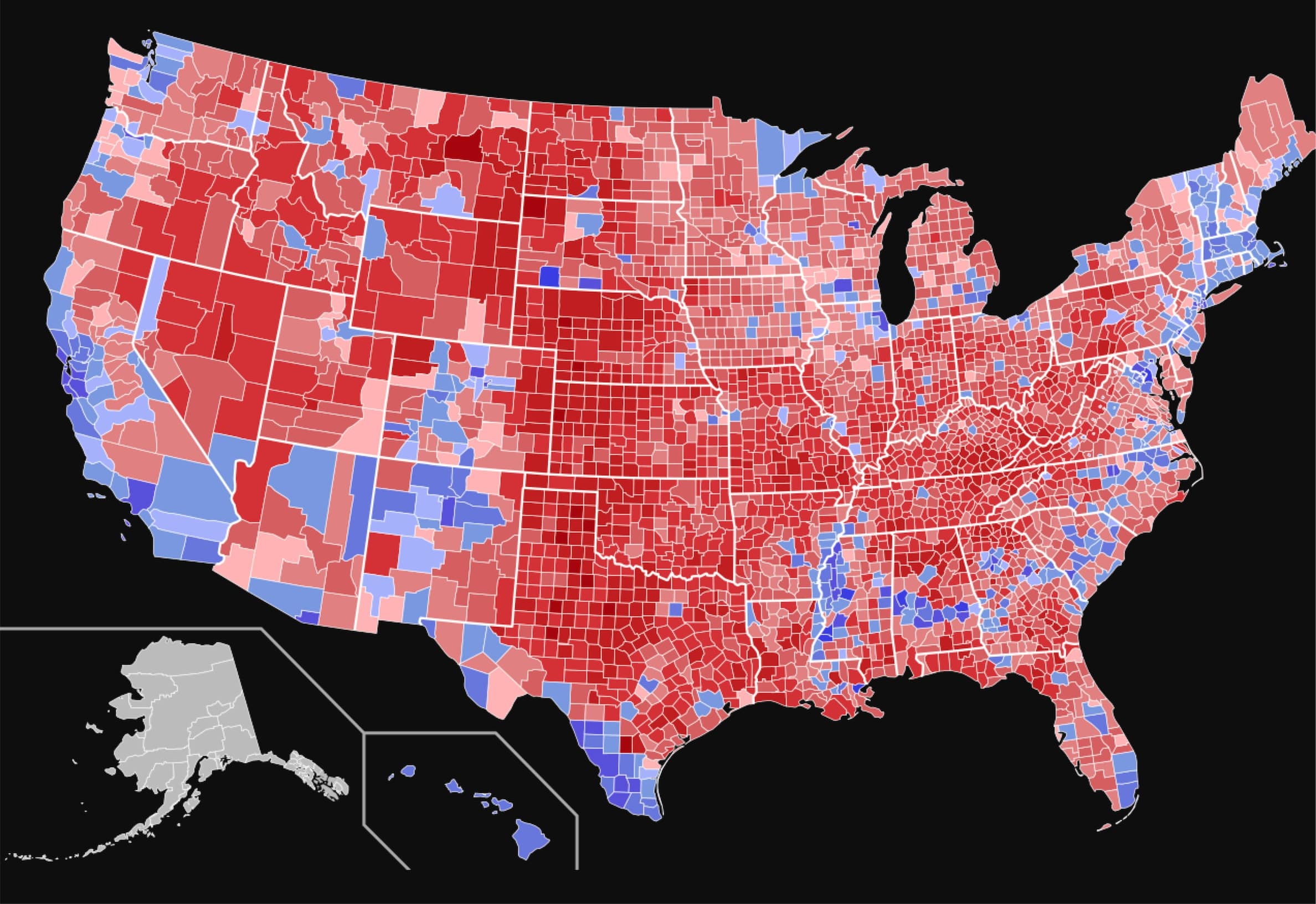

The Electoral College produces tens of millions of meaningless votes in each election. California and Texas, the country’s most populous states, wield a combined 93 electoral votes. We don’t have to wait until election night to know which way they’ll swing: California hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1988, while Texas hasn’t chosen a Democratic contender since 1976.[14][15]

Texas Democrats and California Republicans always garner some House representation, but for presidential elections they might as well not show up. In 2016, almost 3.9 million Texans voted for Hillary Clinton and almost 4.5 million Californians cast ballots for Donald Trump.[16] In these two states, and in 46 others, a vote cast for the candidate who loses the state is a vote that doesn’t count at all. (Nebraska and Maine use a congressional district method that allows candidates to split electoral votes, but even then it usually doesn’t happen).[17]

The United States’ 56% turnout for the 2016 presidential election was a slight increase from the 2012 election, but was lower than the turnout rate of most developed democracies.[18] There are many factors behind this, including perceptions of political corruption and the significance of a single vote. But research led by Reed Hundt, the former director of the Federal Election Commission and chairman of a pro-popular vote nonprofit, shows that a national popular vote would likely increase turnout by 20 to 80 million voters.[19]

This isn’t just about bringing those Texas Democrats and California Republicans to the polls. It’s about bringing the California Democrats and Texas Republicans who thought, rightly, that they didn’t need to vote because their preferred candidate would win anyway.

Candidates have little incentive to campaign in states where they’re so far ahead or behind that the result is a foregone conclusion, meaning they don’t have to prioritize issues important to those voters. They can focus their time, energy, and resources on perennial swing states.[20] In 2012, presidential candidates held general election campaign events in just 12 states. Ninety-six percent of those events were concentrated in only eight states, and two-thirds came in Ohio, Florida, Virginia, and Iowa.

Proponents of the current winner-take-all method used by 48 states frequently argue that a presidential popular vote would empower large states at the expense of smaller ones, that candidates would focus all of their energy on big-city interests, and that small-town, rural America would be ignored.[21]

But the popular vote doesn’t empower large states. By definition, it doesn’t empower any state. It makes everyone’s vote equal.

Rural America is right to feel ignored; its population is dwindling, its economic growth lags behind large urban areas, and public policy hasn’t always kept its interests in mind.[22] But all of that has happened with the Electoral College in place, so to credit the College with boosting rural priorities is to ignore the present imbalance. Rural America is largely ignored in presidential elections not because politicians don’t care about it, but because the battleground states the Electoral College creates aren’t rural.[23]

Besides, the country’s 100 biggest cities account for just one-sixth of its population.[24] The rural dwellers—people living outside metropolitan statistical areas—also account for one-sixth of the population. That, plus the fact that candidates pay roughly equal attention to urban and rural areas within battleground states, indicates that a national popular vote would increase the attention politicians give to rural voters and issues.

Concerns that the country’s largest states, cities, or counties could form an insurmountable voting bloc and decide elections by themselves aren’t founded, either. It assumes that the country’s largest states, cities, and counties vote overwhelmingly for one candidate over another; they don’t.[25] The geographical distribution of voters with certain ideologies renders that outcome virtually impossible.

As for the NPVIC, 12 states and the District of Columbia have signed on.[26]

- California—55 electoral votes

- New York—29

- Illinois—20

- New Jersey—14

- Washington—12

- Massachusetts—11

- Maryland—10

- Colorado—9

- Connecticut—7

- Hawaii—4

- Rhode Island—4

- District of Columbia—3

- Vermont—3

Together they total 181 of the necessary 270 electoral votes to trigger the compact’s terms. The New Mexico and Delaware legislatures have passed the bill; if their governors sign it, the total will jump to 189.[27]

From there the NPVIC’s path to 270 becomes trickier. The remaining states where the bill is most likely to pass are small, left-leaning states that won’t boost the vote total very much.[28] Larger swing states likely won’t forfeit their important role in presidential elections, while large Republican-leaning states will preserve the valuable electoral advantage the Electoral College gives them.

But that doesn’t mean we should stop trying. The president has a number of unilateral powers (see Trump’s national emergency, Barack Obama’s DACA, and Bush’s Middle East military maneuvers). A leader with this sort of unchecked power should be elected as directly as possible by the people, not by a group of largely unknown electors that can, legally, disregard the people’s vote and cast their ballots for whomever they choose.

The popular vote winner has lost the election five times. Three of those elections took place before 1890, then it didn’t happen for 110 years.[29] Now we’ve had two in the last two decades. Besides 2000 and 2016, it almost happened in 2004; had John Kerry received 60,000 more votes in Ohio, he would have claimed the White House despite losing the popular vote by three million. Clinton beat Trump by almost three million votes, but lost the Electoral College by 74.[30] According to Hundt, for the first time in U.S. history, one of every three non-landslide presidential elections will end with the popular vote winner watching their opponent sworn in on January 20.[31]

This anachronistic, inequitable election scheme has long overstayed its welcome. It’s time we championed simplicity by making the presidential election process easier for voters to understand. It’s time we made the presidency like every other elected office in the United States. It’s time we turned the presidential election into a popularity contest.

Because that’s what democracy should be.

[1] NCC Staff. “On this day, Bush v. Gore settles 2000 presidential race.” National Constitution Center. December 12, 2018. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-bush-v-gore-anniversary.

[2] “Bush v. Gore.” Oyez. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.oyez.org/cases/2000/00-949.

[3] Vandermass-Peeler, Alex, Daniel Cox, Molly Fisch-Friedman, Rob Griffin, Robert P. Jones. “American Democracy in Crisis: The Challenges of Voter Knowledge, Participation, and Polarization.” Public Religion Research Institute. July 17, 2018. https://www.prri.org/research/american-democracy-in-crisis-voters-midterms-trump-election-2018/.

[4] “5. The Electoral College, Congress, and representation.” Pew Research Center. April 26, 2018. https://www.people-press.org/2018/04/26/5-the-electoral-college-congress-and-representation/.

[5] “Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote.” National Popular Vote. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/written-explanation.

[6] “News History.” National Popular Vote. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/news-history.

[7] “About.” National Popular Vote. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/about.

[8] “U.S. Electoral College: Who Are the Electors? How Do They Vote?” National Archives and and Records Administration: Electoral College. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/electoral-college/index.html.

[9] U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section X.

[10] Valencia, Patrick C. “Combination Among the States: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is an Unconstitutional Attempt to Reform the Electoral College.” Harvard Journal on Legislation. October 26, 2018. http://harvardjol.com/2018/10/26/combination-among-the-states-npvic-unconstitutional/.

[11] “McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U.S. 1 (1892).” U.S. Supreme Court. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/146/1/.

[12] “Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U.S. 503 (1893).” U.S. Supreme Court. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/148/503/.

[13] Lu, Denise. “The electoral college misrepresents every state, but not as much as you may think.” The Washington Post. December 06, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/how-fair-is-the-electoral-college/.

[14] “California Presidential Election Voting History.” 270 To Win. Accessed March 23, 2019. https://www.270towin.com/states/California.

[15] “Texas Presidential Election Voting History.” 270 To Win. Accessed March 23, 2019. https://www.270towin.com/states/Texas.

[16] “Presidential Election Results: Donald J. Trump Wins.” The New York Times. Updated August 09, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/elections/2016/results/president.

[17] “Split Electoral Votes in Maine and Nebraska.” 270 To Win. Accessed March 16, 2019. https://www.270towin.com/content/split-electoral-votes-maine-and-nebraska/.

[18] Desilver, Drew. “U.S. trails most developed countries in voter turnout.” Pew Research Center. May 21, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/21/u-s-voter-turnout-trails-most-developed-countries/.

[19] Paul, Deanna. “The popular vote could decide the 2020 presidential election, if these states get their way.” The Washington Post. February 26, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/02/26/popular-vote-could-decide-presidential-election-if-these-states-get-their-way/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.d9c906ad3355.

[20] National Popular Vote. “Introduction What It Is – Why It’s Needed.” February 26, 2016. Youtube Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q0rOKo9BWEU.

[21] Posner, Richard A. “In Defense of the Electoral College.” Slate. November 12, 2012. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2012/11/defending-the-electoral-college.html.

[22] Cramer, Katherine J. “The great American fallout: how small towns came to resent cities.” The Guardian. June 19, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jun/19/americas-great-fallout-rural-areas-resent-cities-republican-democrat.

[23] “Myths About Big Cities.” National Popular Vote. December 29, 2015. Youtube Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_gbwv5hf2Ps&t=2s&list=WL&index=3.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Myths About Big Cities and Big Countries.” National Popular Vote. February 06, 2016. Youtube Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kfm6O1Fm14w&index=4&list=WL.

[26] “Status.” National Popular Vote. Accessed March 23, 2019. https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/status.

[27] Fischler, Jacob. “Colorado joins effort to elect presidents by popular vote, go around Electoral College.” Roll Call. March 18, 2019. https://www.rollcall.com/news/campaigns/colorado-joins-effort-to-elect-presidents-by-popular-vote-skip-electoral-college.

[28] Paul, Deanna. “The popular vote could decide the 2020 presidential election, if these states get their way.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Presidential Election Results: Donald J. Trump Wins.”

[31] Paul, Deanna. “The popular vote could decide the 2020 presidential election, if these states get their way.”