Language is one of the most distinguishable founding elements of humanity. It is a basic principle of human development and existence, determining every interaction and relationship. A well known psychological theory championed by Sapir-Whorf states that language isn’t simply how we voice our thoughts; it shapes our ideas and perceptions of reality.[1] In accepting this, it becomes necessary to recognize that harsh and dangerous language, when deployed to describe human life, can perpetuate tangible violence and hatred, all the way from the interpersonal to national level. Several reports go so far as to indicate a direct correlation between the rise of hate speech and related violence, especially following the US 2016 presidential election.[2] Therefore it is imperative to examine the way language and rhetoric shapes a person’s perception of other human beings, both within and beyond debates concerning policy.

One group affected by negative rhetoric and subsequent policies is the immigrant population in America. Apart from the overt prejudices that they face, such as direct discrimination in the labor market, racial and/or ethnic insensitivity and general hostility, there are subtleties in the language used to describe immigrant lives and journeys that affect the common impression of immigrant life.[3] These linguistic nuances are then used to shape immigration policy, becoming institutionalized and ingrained in the collective subconscious that influences the integration, treatment, and possibility of deportation of these individuals.

Immigration in America has a long and storied past, and like most stories, it is best told with words. Yet, the vocabulary used to describe immigrants and immigration in the United States is quite perplexing. Considering it is a nation that was founded on, built by, and continues to depend on immigration, it is appalling that the words used to describe immigrants in America are often degrading to the point of dehumanization. It is this language that has historically advanced policies that scapegoat immigrants, in addition to creating a deep fracture between those who were born in America and those who were not.

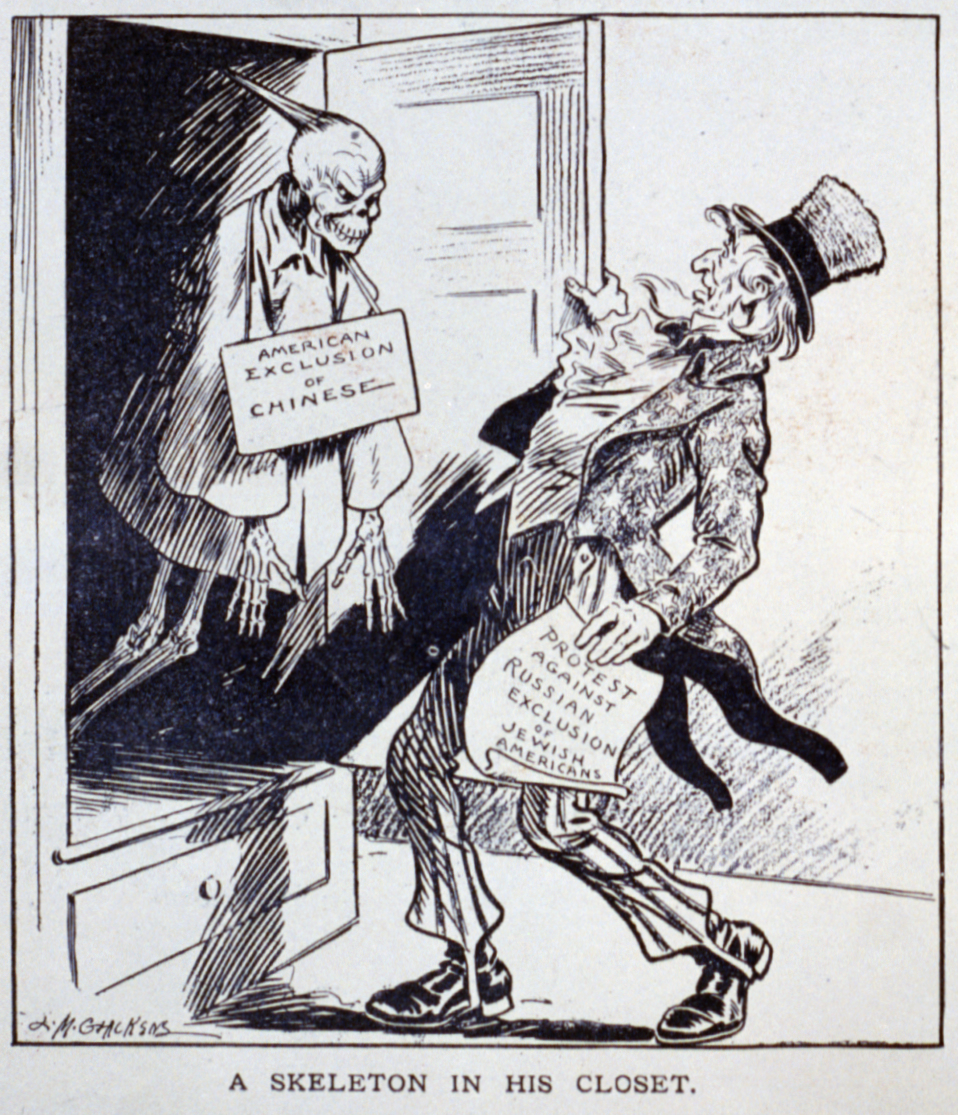

One of the first restrictions placed on immigrants in America was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which, among other things, “suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years” and “required every Chinese person traveling in or out of the country to carry a certificate identifying his or her status as a laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant.”[4] This policy was influenced by Yellow Peril, an inherently racist and popular ideology in the late 19th century that imparted that predominantly white and western civilizations were in danger of being invaded by East Asians.[5] Immediately, the act reduced a significant portion of the population to nothing more than their documentation, while concurrently accusing them of being a threat for simply existing in America. Unfortunately, the legacy of Yellow Peril did not end with the turn of the century; rather, it continues to echo throughout modern media.

Anti-Asian views in the United States were strongly circulated from that point forward, exemplified by the portrayal of Asian individuals in the media. These visuals often comprised a villainous, male occult or else a seductive dragon lady inspired female. Despite nearly two centuries of living in America, people of Asian descent were, and are, depicted as foreigners who speak broken English with a strong accent, preserve only their ‘old country traditions,’ and refuse to assimilate into American culture. [6]

Thus, the Yellow Peril stereotype has left a toxic impression of the “foreign other,” that continues to linger in the mindset of white Americans, and influences the way that Asian Americans are treated on a daily basis.

Another prominent example of discriminatory immigration restriction is the National Security Entry-Exit Registry System that was implemented in 2002, as part of the War on Terrorism, a year after the September 11 attacks occurred. This program mandated registration by all non-citizen visa holders, which promoted racial profiling and harsh treatment such as interrogation and detention.[7][8] The crux of the issue here lies in that most of the targeted nations were Muslim-Arab majority countries, leading to an ever increasing marginalization of this immigrant community. This played an influential role in normalizing the Eurocentric, unfounded, and hostile anti-Muslim sentiment which entails a contrived fear of the perceived threat the Muslim community brings to America.

15 years later, Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign promise of “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” led to Executive Order 13769 which concerns both immigration and refugees. While an Immigrant is an individual who leaves one’s country to settle in another, a refugee is a person who moves out of one’s country due to restriction or danger to their lives — meaning they do not come by choice. Trump’s policy proposal affected both. In addition to the entry-refusal of most people from Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen, the order also called for the discontinuation of the US refugee program for 120 days; reduction in the number of refugees admitted to the United States in 2017 from 110,000 to 50,000; halting of the resettlement of Syrian refugees indefinitely, and launching a screening mechanism for the entry of foreign nationals. [9][10] This discriminatory ban was deemed necessary by Trump in order to protect America from Islamic militants and their subsequent terrorism. Yet he refrained from placing the same restrictions on those commuting from the UAE, Egypt, Indonesia or Azerbaijan ― Muslim majority countries with which he has business ties.[11] This underpins the theory that Trump’s ban was less about the safety of American citizens and more about furthering bigotry. More than protect Americans, the proposed policy encouraged fervent nationalism. Part of that stance was manifested in extensive xenophobia, and can be numerically digested as hate crimes increased a staggering 45 percent against Muslim, South Asian, Sikh, Hindu, Arab and Middle Eastern communities in the US in 2017 alone.[12]

In a joint address to Congress delivered just a few weeks after his inauguration, Trump stated that “the vast majority of individuals convicted of terrorism and terrorism-related offenses since 9/11 came here from outside of our country.”[13]

On the contrary, none of the Muslim-identifying individuals who have committed large scale terror attacks in the US since 2003 have come from these banned countries. Moreover, the majority of America’s terror perpetrators are themselves, American. Take, for instance, the man from Baltimore who admitted to travelling to New York City with the express purpose of murdering black men; or the white neo-Nazi who killed a woman and injured several others during an anti-racism protest in Charlottesville last August; or the man who stabbed two men to death after they attempted to stop him from verbally assaulting Muslim teenagers on the train; or the gunman who murdered 17 people in the Parkland massacre just last month. [14][15][16][17]

Research has shown that between 2001 and 2015, more Americans were killed by right-wing extremists than by Islamist terrorists, and that the average likelihood of an American being killed in a terrorist attack in which an immigrant participated in any given year is one in 3.6 million — even including the 9/11 deaths [18]

Yet politicians, citizens and the media by and large circumvent referring to the large scale, violent acts of white men as terrorism. Instead, the word terrorism is fixed in the American psyche as inherently linked to those of Middle Eastern descent, and even more specifically those who are Muslim, despite the fact that they are not largely responsible for acts of terror in America.

Another group that has been specifically targeted by Trump’s rhetoric and policies are Mexican immigrants. Phrases such as “alien,” “undocumented alien,” and “illegal alien,” have become fixed in American discussions about immigration, specifically around Mexican immigrants, and are immediately associated with a certain notion of life. They conjure an image of a person who is “un-American”; of someone who is lesser, who has come to the United States unlawfully to take the jobs of the more deserving, American-born citizens; of someone who does not contribute to American society, but rather takes away from it. These dehumanizing phrases all carry the potential to cause harm. In recent domestic politics, they have been used most commonly in debates about border security between the U.S. and Mexico. The phrase “illegal alien” was brought up multiple times after Trump launched his presidential campaign by disparaging Mexican immigrants, saying, “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”[19]

Alternately, the term “alien” draws on childhood memories of understanding the word as it pertains to movies and books, describing characters that are unsettling in their peculiarity. It is interesting to note how such a colloquial, childish, and prejudicial term has become rooted in the language used to reference someone who has relocated from another country. By normalizing this term once reserved for six-armed, green-bodied creatures who are determined to destroy planet Earth, a road has been paved for the way children see their classmates. With this language, they may deem immigrant children “aliens,” following which, their side glances or uncomfortable smiles are excused because these “aliens” are speaking or acting in a way that is foreign.

In recent months, protesters railing against Trump’s anti-immigration agenda have adopted the phrase “No human being is illegal,” in their disputation. This simple expression strikes the core of the debate on the validity of a human life. By referring to children, families, or working individuals as “illegal immigrants,” nationalists support the revocation of the non-American’s status as humans. They enforce the insinuation that a person who does not have papers is not a person at all, and that the United States sees those individuals primarily as immigrants and only secondarily as people. It is often forgotten that immigrants are first and foremost humans, because their identity has so frequently been replaced with legal jargon. In so doing, their stories, their families and their unique backgrounds have been replaced with callous and dismissive catch-all terms that fail to say anything meaningful about millions of people. “Illegal” no longer suggests their status as an immigrant. “Illegal” has in fact become synonymous with their lives.

In the best-case scenarios, immigrants transition from “aliens” to “naturalized” citizens. According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service, to become “naturalized” you must undergo a variety of tests, among other qualifications.[20] These tests consist of a speaking exam to gauge an immigrant’s English abilities (they must be able to read sentences aloud), as well as a civics test which consists of 10 questions out of a possible 100. While elements of the naturalization process may be troubling, the term “naturalization” is, in itself, alarming. Merriam-Webster has multiple definitions for “naturalization,” but the one that stands out most is “to bring into conformity with nature.”[21] This definition points a disturbing finger towards the presumed illegitimacy of an immigrant’s previous lived experience. It indicates an erasure of their past customs, language and much more by suggesting the United States is the natural choice; that becoming a citizen provides a sort of allegiance with the U.S. that allows you to be defended. These circumstances aren’t reserved for specific groups of immigrants. They extend to all visa and green card holders. Essentially, any immigrant who is not naturalized is unworthy of defense, placed into a different class of personhood. Until immigrants are naturalized they are seen as the other.

These are only a few among many ways the United States has allowed rhetoric to restrict, and ultimately mistreat, immigrants. These actions set the stage for the dysphemisms used to describe immigrants in addition to the microaggressions and disparaging policies that pose a constant challenge. This hurtful lexicon is exacerbated by president Trump’s repeated vision in which, “it’s going to be only America first, America first.”[22]

The unfortunate truth is that regardless of whether immigrants are categorized as asylum seeker, refugee, visa holder or illegal immigrant, they are coming to this country seeking a new life, a safe haven, and new opportunities. In the most serious of cases, critical time is wasted debating how to label these human beings. In the months and years that have been swallowed by this discussion, countless immigrants and refugees have suffered.[23][24] The fixation on the intricacies of who fits in what category has grown so intense that the actual lives of these people have been pushed aside. The importance of labelling has become such a central part of immigration in America that it has surpassed the humanity it represents. In continually using outdated and harmful rhetoric America has by and large dehumanized its immigrant population. This ultimately points to the failure in both the American government and its populace at large to provide that which it promises: justice for all. Until the stereotypes and injuries that this rhetoric perpetuates is confronted, America will continue to disappoint the communities by which it was founded.

SOURCES:

[1] “Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.” Linguistic Society of America. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/language-and-thought.

[2] “Report: Rise in Hate Violence Tied to 2016 Presidential Election.” Southern Poverty Law Center. Accessed March 25, 2018. https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2018/03/01/report-rise-hate-violence-tied-2016-presidential-election.

[3] “2016 Hate Crime Statistics.” FBI. February 27, 2018. Accessed March 27, 2018. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2016-hate-crime-statistics.

[4] Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs. “Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigration.

[5] Yang, Tim. “The Malleable Yet Undying Nature of the Yellow Peril.” Dartmouth EDU, www.dartmouth.edu/~hist32/History/S22%20-The%20Malleable%20Yet%20Undying%20Nature%20of%20the%20Yellow%20Peril.htm.

[6] Deitch, Elizabeth A., Adam Barsky, Arthur P. Brief, Rebecca Butz, Suzanne Chan, and Jill C. Bradley. “Subtle Yet Significant: Everyday Racial Discrimination in the Workplace.” PsycEXTRA Dataset 56, no. 11 (November 01, 2003): 1299-324. doi:10.1037/e518712013-257

[7] Muaddi, Nadeem. “The Bush-era Muslim Registry Failed. Yet the US Could Be Trying It Again.” CNN. December 22, 2016. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://www.cnn.com/2016/11/18/politics/nseers-muslim-database-qa-trnd/.

[8] “DHS’s NSEERS Program, While Inactive, Continues to Discriminate.” Immigration Impact. August 31, 2015. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://immigrationimpact.com/2012/06/28/dhss-nseers-program-while-inactive-continues-to-discriminate/.

[9] CNBC. “US Court Says Trump Travel Ban Unlawfully Discriminates against Muslims.” CNBC. February 15, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/15/us-court-says-trump-travel-ban-unlawfully-discriminates-against-muslims.html.

[10] “President Trump’s Executive Orders on Immigration and Refugees.” The Center for Migration Studies of New York (CMS), 14 Feb. 2017, cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/.

[11] “FACT CHECK: Does President Donald Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban’ Exclude Countries Where He Has Businesses?” Snopes.com. January 31, 2017. Accessed March 25, 2018. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/trumps-muslim-ban-exclude-countries-businesses/.

[12] Yam, Kimberly. “Trump Invoked In 20 Percent Of Hate Crimes Against South Asians, Middle Easterners, Report Says.” The Huffington Post. February 23, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2018.

[13] “Remarks by President Trump in Joint Address to Congress.” The White House. Accessed March 27, 2018. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-joint-address-congress/.

[14]Southall, Ashley. “Suspect in Manhattan Killing Hated Black Men, Police Say.” The New York Times. March 22, 2017. Accessed March 29, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/22/nyregion/manhattan-nyc-james-harris-jackson-hate-crime.html.

[15] Rankin, Sarah. “Officials: White Nationalist Rally Linked to 3 Deaths.” AP News. August 13, 2017. Accessed March 29, 2018. https://apnews.com/b8560c3ebaac4deb9043bb695f2eb1db.

[16] Ryan, Jim. “2 Killed in Stabbing on MAX Train in Northeast Portland as Man Directs Slurs at Muslim Women, Police Say.” OregonLive.com. May 27, 2017. Accessed March 29, 2018. http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2017/05/police_responding_to_ne_portla.html.

[17] Anderson, Curt. “Parkland Shooting Suspect Cruz Appears in Court, Remains Silent When Asked about Plea.” PBS. March 14, 2018. Accessed March 29, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/parkland-shooting-suspect-cruz-appears-in-court-remains-silent-when-asked-about-plea.

[18] Nowrasteh, Alex. “Terrorism and Immigration: A Risk Analysis.” Policy Analysis, no. 798 (September 13, 2016).

[19] Staff, TIME. “Donald Trump’s Presidential Announcement Speech.” Time, Time, 16 June 2015, time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/.

[20] “How to Apply for Naturalization.” USCIS. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.uscis.gov/us-citizenship/citizenship-through-naturalization.

[21] “Naturalize.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/naturalize.

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/saalt-hate-crimes-report_us_5a7390fee4b01ce33eb12ae4.

[22] “Donald Trump: ‘America First, America First’.” BBC News. January 20, 2017. Accessed March 20, 2018. http://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-38698654/donald-trump-america-first-america-first.

[23] Alvarez, Priscilla. “What the Waiting List for Legal Residency Actually Looks Like.” The Atlantic. September 21, 2017. Accessed March 27, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/09/what-the-waiting-list-for-legal-residency-actually-looks-like/540408/.

[24] “Waiting List for Legal Immigrant Visas Keeps Growing.” CIS.org. Accessed March 27, 2018. https://cis.org/Vaughan/Waiting-List-Legal-Immigrant-Visas-Keeps-Growing.