This article is the first installment of a column dedicated to addressing the problems jury duty both faces and creates. Juries often go undiscussed; when they are, the central theme is that juries are essential despite the associated inconveniences. My column will question why we remain passive about such an extremely flawed institution, especially when its problems can be addressed. It’s time to take a closer look at jury duty.

When my mother became a U.S. citizen, she swore allegiance to her new country. She pledged to “support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic…[and] bear true faith and allegiance to the same.”

Some of these laws my mother committed to uphold prohibit certain actions. Do not speed. Do not steal. Do not kill. Other laws serve as requirements that citizens must fulfill. Pay your taxes. Educate your children. Attend jury duty.

It was the last rule my mother habitually avoided. When summoned for jury duty, she feigned incompetence in English to avoid having to attend. As a child, I was curious as to why she would lie to evade something she was legally required to do. Like the little annoying brat I was, I called her out, harassing her about how lying is immoral. As my mother set the phone down, she looked at me calmly, unfazed by my teasing. She explained that she was not lying maliciously, but because she could not afford to take days off of work. She acknowledged that lying is wrong, but noted that she had no choice because telling the truth would not help her case. She claimed that the courts would reject her claim of financial hardship because of her income, even though she was a single mother raising two children. She was right; even if she provided ample supporting documentation, financial hardship exemptions are given solely at the court’s discretion.

Jurisdictions that pay jurors a flat daily fee pay an average salary of $22 per day, while jurisdictions that increase wages the longer one serves pay an average of $32 per day. On federal minimum wage alone, a person makes $58 during an eight-hour work day, meaning they would lose $26-36 if they missed just one day of work for jury duty. My mother, a nurse practitioner, would be losing much more.

As Forbes writer Josh Barro put it, “for a lot of salaried professionals, jury duty means being at the courthouse from 8 to 4 and then going into the office to attend to a slew of matters that only…[they] are equipped to handle.” My mother was the only practitioner in her clinic certified to do Department of Transportation (DOT) physicals. Furthermore, as the clinic’s only practitioner with a teaching background, she was tasked with training recently graduated nurses. Nobody else could fill those roles.

If my mother had attended jury duty, she would have been in court for seven hours, then had to rush to administer DOT physicals, while also training new nurses—just to keep the clinic from shutting down for the day. My mother knew that if she took time off, she would be compromising her own salary, as well as the salaries of her fellow nurses. Worst of all, if she had attended jury duty without taking time off, she would have been working tirelessly to complete her civic and professional responsibilities without proper compensation.

Even though my mother’s situation shows the impracticality of jury duty, it was still possible for her to serve while losing only a fraction of her income. For others, serving can mean losing a lot more. Federal law does not require an employer to compensate an employee for jury duty. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that 39% of workers do not receive paid jury leave. Because there is “a strong correlation between socioeconomic status and minority status … jury-related financial hardship disproportionately affects minorities.” In August 2016, Terrell Marshall Law Group PLLC and the Law Office of Jeffrey L. Needle filed a class action lawsuit against King County, Washington, noting that the juror rate of $10 per day excludes people who do not receive paid jury leave from their employers, disproportionately affecting people of color. As of September 2018, the case is still pending.

In April 2018, the federal juror wage was raised from $40 to $50 a day. The raise, which came 28 years after the last wage hike, resulted from a single paragraph in a 2,232-page spending bill signed by President Trump to avoid a government shutdown. The raised wage still sits below federal minimum wage and has not kept up with inflation. Outside of the federal system, a juror’s wage is completely dependent on the state and even municipality they serve in, meaning reform can take significantly longer. In Texas, juror pay remained $6 a day for fifty years, increasing to $40 in 2006.

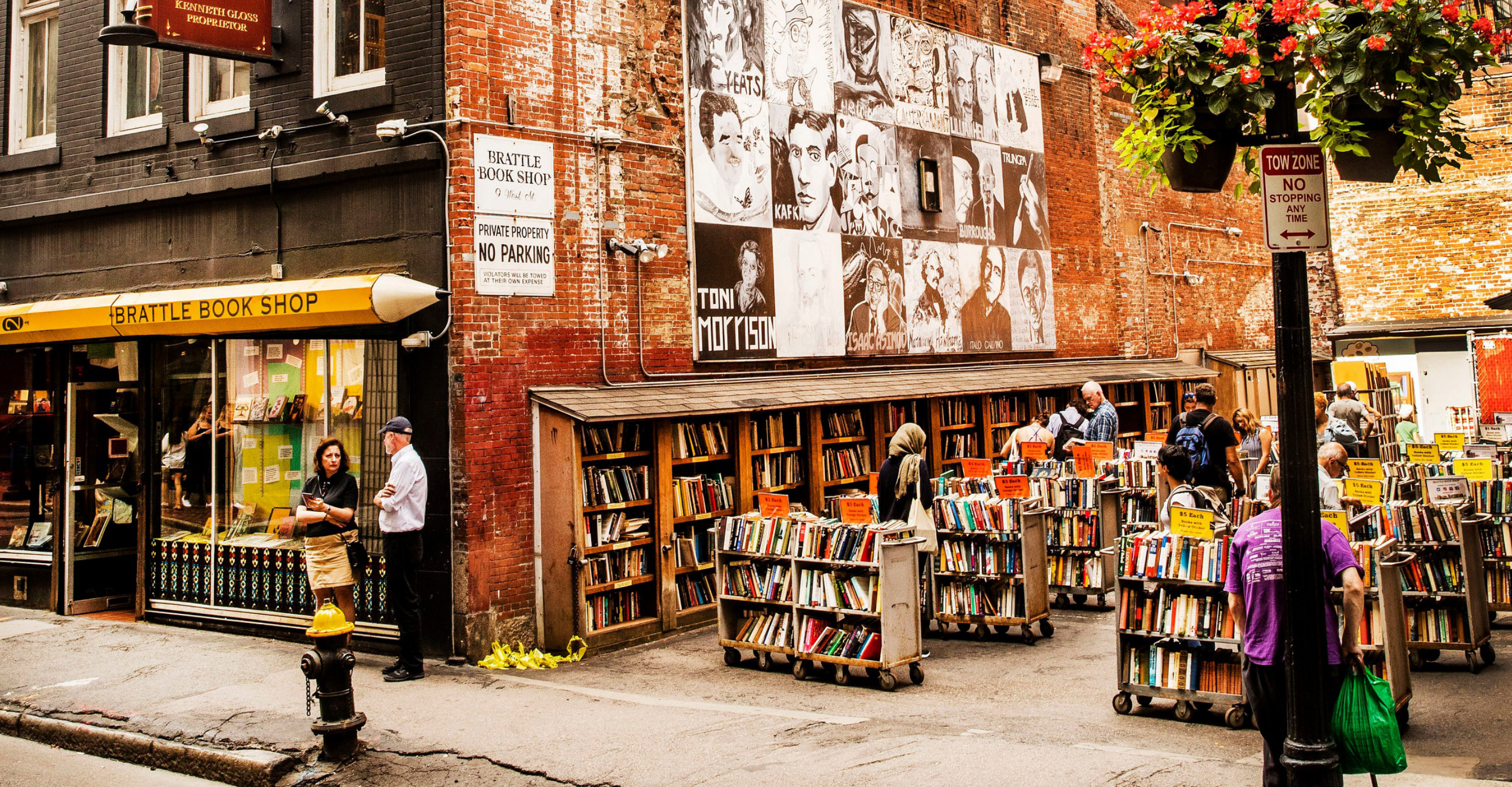

The federal government, as well as states and localities, should raise juror wages to their respective minimum wages. For employees who earn more than their state’s minimum wage, employers should pay the difference. Eight states–Alabama, Louisiana, Nebraska, Tennessee, Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York–require an employer to do just that. However, each state has limitations depending on the form of employment or length of duty. Alabama mandates employers must provide paid time off for full-time employees, but has no such requirement for part-time or temporary employees. Meanwhile, Massachusetts requires employees be paid for the first three days of jury service regardless of employment status. Of the eight states that require employers provide paid jury duty, four lean conservative. That typically pro-business conservatives have made steps to reform jury pay may be an indication of future bipartisan support.

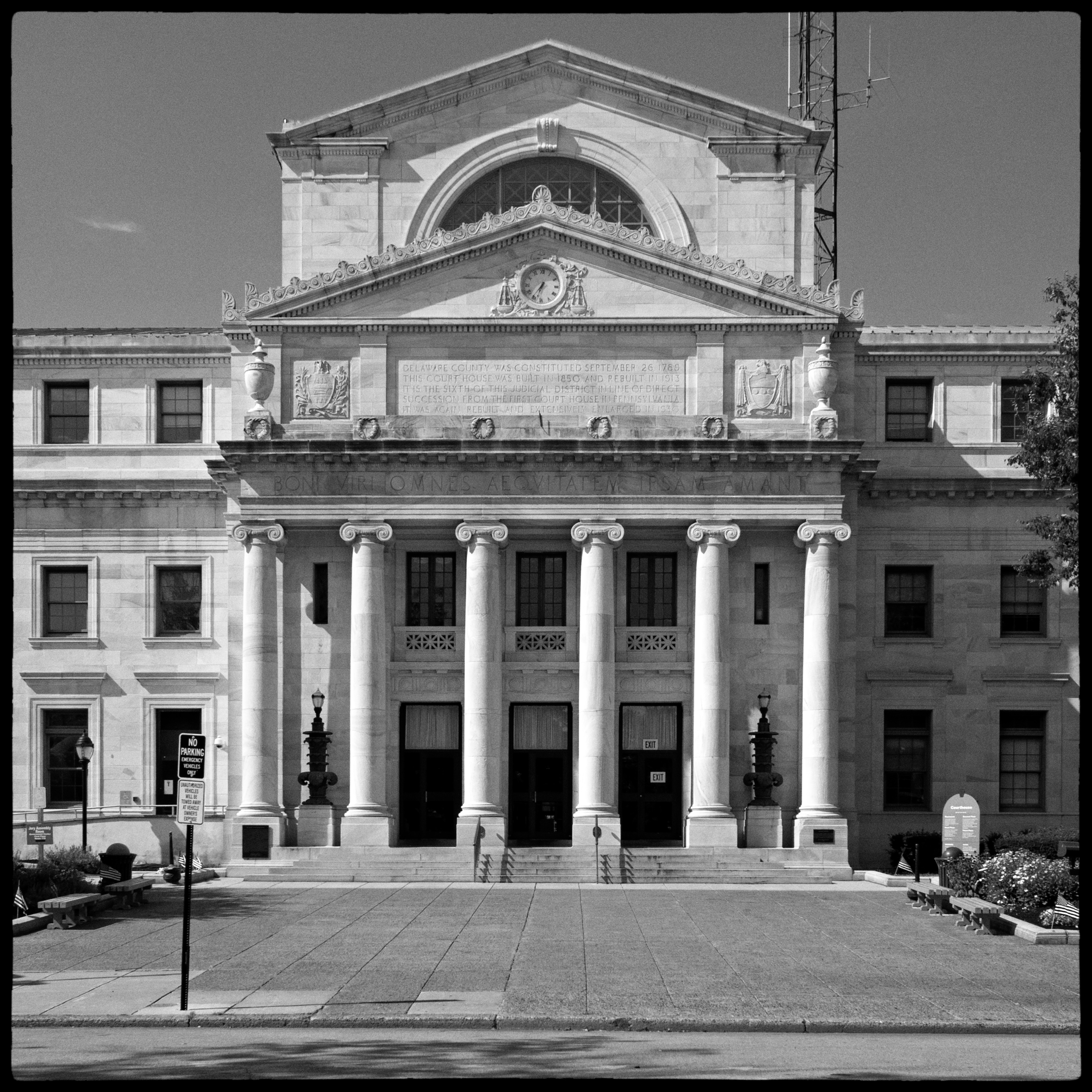

Democracy depends on citizen participation, and retaining jurors requires addressing the issues that often drive them away. Since minorities face higher levels of jury-related financial hardship, inadequate pay lowers jury diversity, making a fair trial less likely. Sometimes participation is inconvenient. But some inconveniences regarding participation can be solved.

It is our responsibility to stay informed and demand action when injustices prevent people from participating in the judicial process. If we stay passive about the issues that face our communities, our states, and our country, those issues will only persist.