Every movement we’ve ever had has sprung from another.

I’m taking a freshman-level course in my final semester at Northeastern. Call it what you will, but I’ve found it’s extremely helpful in reevaluating my education and my perspective on more than just books. In week three, we spent the bulk of our time learning foundational literary theories that frame criticism and research today. We moved from close reading (the practice of sounding out, seeing images in, and questioning each letter on the page) to deconstructionism (thinking each text has a subversive true meaning that contradicts what it says, so basically everything is a lie) to feminist theory (ah, the male gaze) to queer theory and more. My professor said at one point, as we quickly ran through the more recent theoretical approaches, that they all stemmed from identity politics. The feminist theorists questioned why male literature was dominant and preferable to female literature; the African-American theorists pressed for a consideration of why white literature was in the canon but black writers were not; the postcolonial theorists asked how exactly writers of colonized countries could be writing about anything other than a postcolonial experience. All of these movements in literary criticism were pushed by groups who identified in support of some greater representation of people, to have their voices be added to the mix of world literature. They examined the existing field of literature, explained how their particular group deviated from the existing field, and then challenged the terms that existed to define literature so that their approach would be included. All because they were excluded in the first place on the basis of identity.

I wondered how this applied elsewhere, or if my study of English was both the dawn and end of identity politics enacting change. And that brought me to thinking of a place, area of study, or phenomenon that did not, in some way, evolve under the influence of identity politics. And I’m still trying to find the answer to that question. See, identity politics truly is inescapable as long as hierarchies exist that place people with certain identities on the lower rungs of the ladder. The question first asked is, “Why are we down here?” And then, “Well, since we should get up there, how do we do that?” And so we rally around our identity and the people who share that experience with us, rearranging the hierarchy and creating the social equity we deserve. All of this begins with identity politics.

Change comes in waves, and waves are initiated by a deep sense of individual alignment with community values. One of the fastest ways to gather together, as a community, is through identity. Most of the time, it just occurs naturally. I know that when I’m in a space with other Indian Americans I gravitate toward them because of a shared identity, shared history, and shared culture. I feel both safe and supported. And as we start talking about what we face together, I get ready to start moving with them, fighting with them, and what do you get? A movement.

If we think that ignoring identity politics is the answer, then we are wrong, plain and simple. Many, but most notably Mark Lilla of Columbia University, believe the election results reflected misused identity politics by the Democratic Party.[1] I won’t say that’s completely untrue. The Democratic Party has been built off of minority interest groups, while its policies only weakly reflect the interests of those identities. And yet, it has seriously taken an initial step to consider its constituents’ wants and needs. Though far from complete, it has considered identity politics to be an asset. Identity politics is not at the root of the Democrats’ loss, but they need to very seriously consider how they were using them and whether they were serving their constituents to the fullest extent.

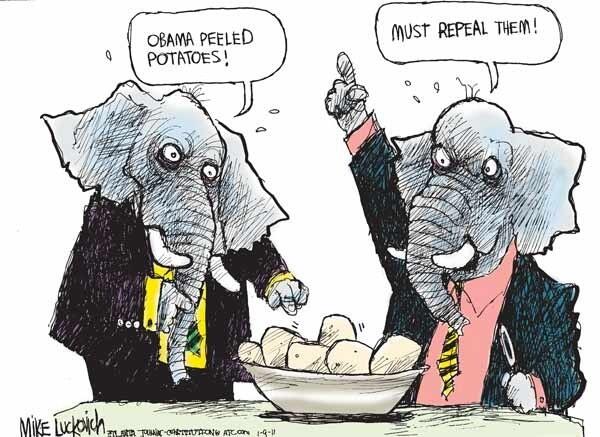

Conversely, the Republican win is also deeply rooted in the politics of identity. Of all the groups and constituencies that turned out to vote in the general election of 2016, one group wildly overperformed: the suburban and urban white male population. Many assume the white vote was singlehandedly necessary to secure a win, as it wildly favored Trump over Clinton.[2] But this is not because of a lack of identity politics – Trump appealed to their identities. Ignoring identity politics fails to recognize that the majority of Trump voters, primarily identifying with their white or male identities, acted based on their identity.

Michael Tesler of the University of California at Irvine explains the growing trend of white Republicans who vote based on racial resentment and its direct connection to Trump’s appeal to white conservative voters.[3] Furthering the trend, it became clear that “Trump has been willing to go where most Republican presidential candidates haven’t.” The explicit and implicit appeals to white voters, and against people of color and immigrants, became a focal point of Trump’s campaign. He painted a glorified image of an America that did not welcome immigrants purely because they were taking jobs he believed were reserved for white people. This rhetoric not only divided Americans into white and non-white, but also drew upon existing racial resentment, characterized by the racist notion that “race-based inequality is due to cultural deficiencies.” This belief has existed amongst white Republicans, according to 2008 and 2012 Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project data that Tesler cites, but it failed to significantly energize white voters with previous nominees John McCain and Mitt Romney. Trump was a much more popular candidate to this race-resenting white voting population of the Republican Party.

Clouding the election in terms of appeal to the “working-class” or “blue-collar voters” deviates from the real crux of the issue: These voters largely identified with Trump through whiteness and the common ground of being male. Trump crucially attracted these voters through his support of their identities, promising that the threat of minority groups, primarily people of color, would dissipate through his presidency and return to them some of the wealth they thought had been stolen.[4] Consequently, the Democrats weren’t able to use his various calls against minorities to unite the Left in 2016. This war of identities did not begin with the 2016 election, but it was exacerbated. And it will continue to quintessentially be a part of our politics in elections to come.

On the other hand, where white voters overwhelmingly went for Trump, Clinton managed to underperform in the votes of people of color and minority groups, groups that typically carry a Democratic candidate through to the White House.[5] The Democratic Party has historically presented itself as the only party dynamically concerned about people of color, most notably in the election of President John F. Kennedy. As Matthew Delmont explains in The Atlantic article titled, “When Black Voters Exited Left,” Kennedy’s win heavily depended on black voters.[6] But upon Lyndon Johnson’s passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it became clear that “there is a gulf between what black Americans hoped the legislation would achieve and what Democratic politicians actually delivered.”

The notion that the Democratic Party will adopt and deliver on “progressive” policies time and time again for people of color is one that is ideologically flawed. The 2017 Democratic National Committee elections brought this to light, in many ways, through upholding the party’s archaic acceptance of donations from corporate political action committees.[7] This decision was not only unsurprising but also uninspiring for progressive voters, many of whom are people of color, who may already be doubtful of the party’s support for their interests. Furthermore, Tom Perez, newly elected DNC chair, has already mentioned strategy for upcoming elections. In response to a question regarding Republican strongholds over certain areas of the United States, Perez said, “We have allowed so many ZIP Codes to be ignored. Our message in rural America is just as powerful as it is in urban America. But because we haven’t been a physical presence there in any sustained way, we have a lot of voters there who no longer believe that the Democratic Party is still working for them… But we have to be out there everywhere talking about it.”[8] The DNC’s first stated priority is getting back those voters, predominantly white and rural, and getting the message out to them.

In the wake of an election lost due to underperformance, especially of the black vote, the Democratic Party needs to welcome identity politics into its platform holistically, rather than picking generalized moderate platform interests that support corporate donors and the white vote.[9] The failure to do so will result in the continued loss of its most powerful and existing base, which has been hesitant to trust that this party will deliver on its interests. Based on the Democratic rebuttal to Trump’s address to a joint session of Congress, the party currently appears to be uninterested in inspiring these voters again, as noted by its representation of a small Kentucky diner bringing together white voters (the constituency the party feels it lost the most) and one black voter (who truly represents the constituency that the Democrats will inevitably lose the most if they begin ignoring identity politics for their real base).[10][11]

Aptly noted, there simply is no other way to do politics than to do identity politics.[12] Calls to remove identity politics from party focus areas will ignore real concerns of voters who naturally view their status, as a group or community, through their identities. They hope to see that status reflected in politics so that they may participate in a government that understands their wants and needs. As identity politics course through every movement, every hierarchy, and even in the way we read books that pressure others to read from a different point of view, we find that it is irrevocably tied to politics. We call it “identity politics” for a reason, and its place in politics is as clear as politics is to its name.

SOURCES:

[1] Lilla, Mark. “The End of Identity Liberalism.” The New York Times. November 18, 2016.

[2] Fidel, Emma. “White People Elected Trump.” VICE News. November 9, 2016.

[3] Tesler, Michael. “Trump is the First Modern Republican to Win the Nomination Based on Racial Prejudice.” The Washington Post. August 1, 2016.

[4] Friedersdorf, Conor. “Donald Trump’s Threats Against Minorities Are Unifying Democrats.” The Atlantic. July 26, 2016.

[5] Luhby, Tami. “How Hillary Clinton Lost.” CNN Politics. November 9, 2016.

[6] Delmont, Matthew. “When Black Voters Exited Left.” The Atlantic. March 31, 2016.

[7] Scher, Bill. “The Resistance Will Be… Underwritten By Corporations.” Politico Magazine. March 8, 2017.

[8] Finnegan, Michael. “Democrats Abandoned Rural America: Won’t Happen Again, Says New DNC Leader.” The Los Angeles Times. March 21, 2017.

[9] Peters, Jeremy W., Richard Fausset and Michael Wines. “Black Turnout Soft in Early Voting, Boding Ill for Hillary Clinton.” The New York Times. November 1, 2016.

[10] “Democratic Response to Trump’s Address to Congress, Annotated.” NPR Politics. February 28, 2017.

[11] Rappeport, Alan, Matt Flegenheimer and Peter Baker. “Trump Addressed Joint Session of Congress For the First Time.” The New York Times. February 28, 2017.

[12] Yglesias, Matthew. “Democrats Neither Can Nor Should Ditch ‘Identity Politics.’” Vox. November 23, 2016.