On Monday, November 14th – six days after the presidential and congressional elections – I piled into an Enterprise rental car with a few friends, and we made the short trip up to Nahant, MA. Representative Seth Moulton was holding a town hall meeting at the public library there, and we hoped to speak to him or to one of his staffers about a bill related to U.S. funding for global health initiatives.

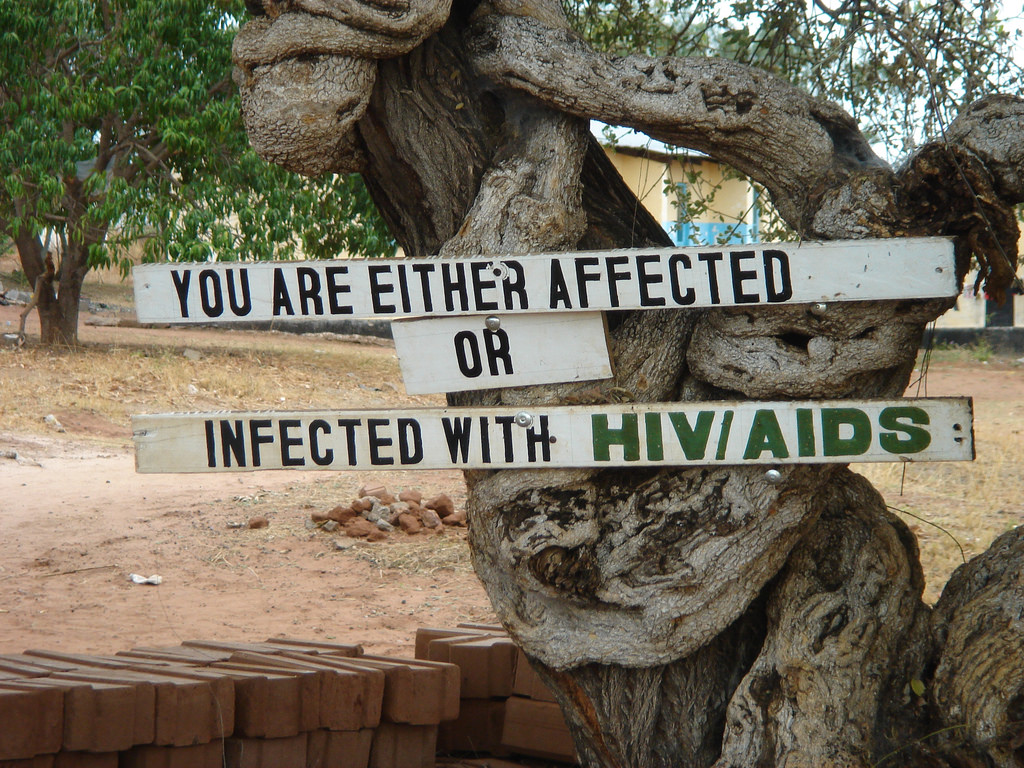

But let’s back up. You might not have realized that our government puts money toward improving the public health of developing nations. It does; in fact, we are “the largest funder and implementer of global health programs worldwide.” [1] In this realm, the U.S.’s most significant effort to date is PEPFAR, or the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The ongoing initiative, which President Bush put into action in 2003, has slashed the HIV-related mortality rate in the countries that it targets – from Angola to Zimbabwe and approximately 50 countries in between. Some evidence shows that PEPFAR has resulted in a 16 to 20% reduction of mortality from any cause in its African countries of interest.[2] Furthermore, the initiative continues to support life-saving drug treatment for 11.5 million men, women, and children around the world with HIV. [3] PEPFAR drastically altered the trajectory of an epidemic that once seemed unstoppable, and its success is a testament to what sustained bipartisan support of a global health program can achieve.

We do more than just PEPFAR, though. Via many different modalities, the U.S. budget includes health-related assistance to more than 60 low- and middle-income countries. Our government acts as a direct operator of global health programs, a partner with other governments/NGOs/the private sector, and a participant in international health organizations. In order to reach global socioeconomic benchmarks set by the UN for the year 2015 (known as the Millennium Development Goals), this funding has become more of a national priority over the last decade. In 2006, we spent $5.3 billion on global health. For 2017, our global health budget request reached an all-time high of $10.3 billion.[4] For someone like me, who considers himself a member of the right to health movement, this statistic is heartening. The protection of the right to health is not merely a domestic concern; it is a concept that crosses all borders. Yes, I do believe that the United States has the responsibility to guarantee access to health care to its own citizens. Yes, I do find it troubling that target 30 million Americans currently live without health insurance.[5] I also find it deeply troubling that, despite the failure of the American Health Care Act, a GOP-sponsored healthcare reform law that would substantially increase this number has a strong chance of passing at some point in 2017. Even so, I am infinitely more disturbed by the idea of widespread preventable death in developing countries. Let me say it another way: Millions of global citizens die every year from afflictions that have simple cures and that have not killed large numbers of Americans in over a century. Surely, if an American lacking affordable access to health care counts as a human rights violation, a Liberian or Cambodian lacking any access to health care – and often lacking clean water and adequate nutrition as well – constitutes something much more severe.

Perhaps you still haven’t been convinced that health is a fundamental human right, though. Even if you have been, perhaps you don’t think that our government has the obligation (or the authority, or the cultural competency) to protect the rights of non-Americans. I share your concern that these efforts can easily become misplaced and even detrimental; maybe a follow-up column that pits the white-savior industrial complex against the concept of accompaniment will be necessary.[6] [7] But above all, I believe that our global standing both allows and compels our nation to intercede at the sight of foreign injustice. Even if these interventions require increased conscientiousness or an adjustment to our national budget, we cannot ignore the call to minimize suffering, stop preventable deaths, and lessen abject poverty. I see the existence of these disparities as a moral imperative – something that demands us to act – but I understand that you might not. Thankfully, there are other reasons why any American should support our government’s commitment to global health. Let’s return to the November 14th town hall meeting where I heard Seth Moulton speak.

You need to know that Seth isn’t some career politician. He’s a 38-year-old former Marine who enlisted just a few months before the September 11th attacks and served four tours in Iraq. Moulton joined the House of Representatives in 2014, and as you might imagine, he has shown a particular interest in veterans’ issues. He also seems to have a higher-level understanding of how war works and how it fails; indeed, he served as a special assistant to General David Petraeus during two of his tours. With all of that experience in mind, I was rather taken by an idea that he supported in the library that morning. Moulton strongly emphasized his belief that an international war against terror will never succeed without international aid and diplomacy. He spoke of a downward spiral – a never-ending cycle of violence and upheaval in certain regions of the world that will continue unabatedly if all we do there is fight.

Plenty of research supports this claim; the links between food insecurity, poor health, political instability, and violent conflict are clear.[8] [9] Certainly, we need to dedicate significant resources to fighting terrorist groups when they are strong enough to commit atrocities, but maybe we can also try to prevent their rise in the first place. In other words, we could identify countries that experience dismal health outcomes and that are at high risk for instability – and then respond with meaningful investments in food, water, and care. Maybe violent unrest wouldn’t be so prominent in regions where bellies are filled and care is freely given. Maybe anti-Western ideology wouldn’t take root so easily where Americans are involved in that feeding and caring.

To be sure, we already do this type of targeted encouragement of stability, but we could make that strategy much more of a priority. Even though our government allocates more money to global health than ever before, our commitment to these programs has plateaued over the last few years ($10.2b in 2014, $10.1b in 2015, $10.2b in 2016, and $10.3b in 2017).[10] I believe that this figure should start to increase at a rapid rate once again – especially in contrast to the U.S. defense budget, which currently hovers just below $600 billion per year.[11] I am not necessarily disputing that peacekeeping through military presence is important in certain countries, but I am suggesting that the balance should continue to shift toward peacemaking through health-focused intervention.

If the United States started to see itself as the global health corps in addition to the global peacekeeping force, it might begin to snuff out violence and terror a bit more easily. That’s what Rep. Moulton thinks, at least. In any case, this approach (if responsibly executed) would likely improve the health of countless individuals – particularly in places where the right to health is so difficult to obtain. For both of these reasons, we as American citizens need to remind our neighbors and representatives that global health financing is vital. We cannot allow the new administration to act on its skepticism about such life-sustaining programs as PEPFAR.[12] (Relatedly, we cannot believe that building walls and instituting bans do anything but permit suffering and plant seeds for future violence.) In short, we cannot stand for ideas like “America First” that lack any nuance. The U.S. does not play a zero-sum game when it commits to global health; instead, everyone benefits. The human rights of global citizens receive protection, but so does our own country’s national security.

Sources

[1] “The U.S. Government and Global Health,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 19, 2016. http://kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-u-s-government-and-global-health/

[2] Richter, Ruthann, “740,000 lives saved: Study documents benefits of AIDS relief program,” Stanford Medicine, May 15, 2012. https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2012/05/740000-lives-saved-study-documents-benefits-of-aids-relief-program.html

[3] “PEPFAR Latest Global Results 2016,” U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, 2016. https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/264882.pdf

[4] “The U.S. Government and Global Health,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 19, 2016. http://kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-u-s-government-and-global-health/

[5] “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 29, 2016. http://kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

[6] Cole, Teju, “The White-Savior Industrial Complex,” The Atlantic, March 21, 2012. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

[7] “Paul Farmer: ‘Accompaniment’ as Policy,” Harvard Magazine, May 25, 2011. http://harvardmagazine.com/2011/05/paul-farmer-accompaniment-as-policy

[8] Maxwell, Daniel, “Food Security and its Implications for Political Stability: A Humanitarian Perspective,” Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, September 13-14, 2012. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cfs_high_level_forum/documents/FS-Implications-Political_Stability-Maxwell.pdf

[9] Brinkman, Henk-Jan, and Cullen S. Hendrix, “Food Insecurity and Violent Conflict: Causes, Consequences, and Addressing the Challenges,” World Food Programme, July 2011. http://www.wfp.org/content/occasional-paper-24-food-insecurity-and-violent-conflict-causes-consequences-and-addressing-

[10] “The U.S. Government and Global Health,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 19, 2016. http://kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-u-s-government-and-global-health/

[11] “Department of Defense (DoD) Releases Fiscal Year 2017 President’s Budget Proposal,” U.S. Department of Defense, February 9, 2016. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/652687/department-of-defense-dod-releases-fiscal-year-2017-presidents-budget-proposal

[12] Cooper, Helene, “Trump Team’s Queries about Africa Point to Skepticism about Aid,” New York Times, January 13, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/13/world/africa/africa-donald-trump.html