For Mike, every day is the same. Shivering nights mercifully give way to morning while he watches the people in his neighborhood get ready for school and work. Although Mike has no job, he has the same plan every morning, afternoon, and night: make money to score heroin. Tuesday is trash day, which means hundreds of recycling and trash bins are filled with used cans and bottles that Mike can collect and exchange at the local supermarket. When Mike can’t find enough money to pay for his habit, he resorts to more violent measures to satisfy his craving, and stave off the deleterious effects of withdrawal.

Mike is not alone in his addiction. The U.S. comprises just 5 percent of the world population, yet it consumes two-thirds of the world’s illicit drugs.[1] According to the U.S. Department of Health 2010 National Survey on Drug Use, an estimated 9 percent, or 23 million Americans, age 12 and older, were classified with substance dependence or substance abuse.[2] Of the estimated 7 million Americans classified with illicit drug dependence, roughly 10 percent received treatment for their addiction.[3] Instead of treatment, most drug addicts frequently experience social isolation, rejection and trouble with the law.

The current model in the United States for dealing with drug addiction is centered on law enforcement and incarceration as deterrent measures, part of a larger War on Drugs. This model has failed catastrophically — prisons are overcrowded at the expense of the American taxpayer. Imprisoned addicts are never rehabilitated; instead, their addiction is fueled by drug proliferation inside prison walls. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University found that 65 percent of U.S. inmates meet medical criteria for substance abuse addiction, but only 11 percent receive any treatment.[4]

Traditional drug policy goals of prevention, treatment, and enforcement are means to an end, not ends in themselves. It is time for the United States to formulate alternative drug policies that focus on harm reduction, promote recovery, and challenge the taboos around drug addiction. These directives are an essential reformation of drug strategy, framing drug addiction as a public health issue.

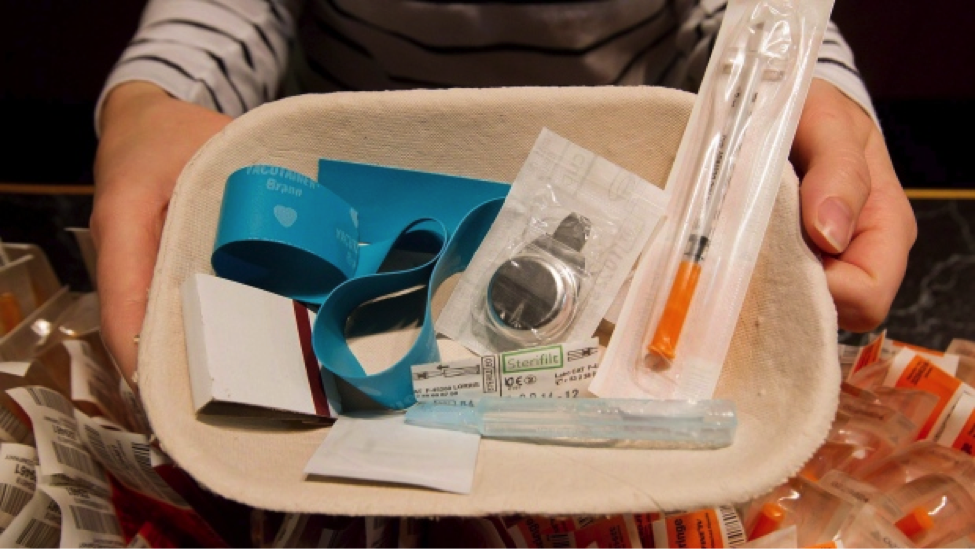

Harm reduction programs have a significant role in mitigating the risks and hazards associated with drug use. However, the U.S. does not need to create models for public health drug policy from scratch. Successful implementation of harm reduction programs has been well documented in other countries, specifically the InSite initiative in Vancouver, Canada. InSite provides users with a safe, sterile environment to self-administer IV drugs. InSite seeks to address essential problem areas, including overdosing, health services, and the costs for incarceration associated with the use of drugs by injection.[5] By partnering with rehabilitation centers and community recovery resources, InSite provides addicts with more than clean needles and a place to shoot up – it also provides opportunities for addicts to begin the recovery process.

Although initially controversial, the program is supported entirely by proven medical evidence and well documented research conducted by third party analysts. The British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS found that overdoses in the Vancouver area decreased by 35 percent over three years, with over 1.8 million visits to the facility.[6] Additionally, no fatalities occurred on the site and admissions or referrals to detox and treatment programs were between 33-42 percent.[7]

Despite the monumental success of InSite and similar programs implemented in countries like Sweden, Germany, and Norway, no attempt has been made to create such a program in the U.S. A counter-argument to the development of such sites could be the financial cost, especially given the current state of the American economy. The Justice Policy Institute estimates the annual cost of incarcerating a drug offender to be between $20,000-$30,000, while the annual cost of treatment is $4,000.[8] Law enforcement interdiction and enforcement efforts will cost taxpayers $14.7 billion in fiscal year 2014,[9] and the DEA estimates less than 10 percent of illicit drugs are captured.[10] In contrast, $9.3 billion will be spent on treatment and recovery. Treatment is a more cost-effective option: every $1 spent on treatment outside prison for cocaine addiction yields $7.48 in societal benefits compared to $1.91 for treatment in prison.[11] The cost of treatment would not be an additional burden on taxpayers if existing funds were appropriated from enforcement and interdiction to treatment and recovery.

Another potential counterargument to harm reduction is the most simple and obvious: giving drug users the message that doing drugs is acceptable is not going to change behavior. Some opponents also believe that providing needle exchanges and other harm reduction services enables drug users. These claims, while valid, ignore the risk-taking propensity of drug users. Drug addicts, and even non-addicts, are going to do drugs regardless of how law enforcement interdiction efforts attempt to deter such behavior. The War on Drugs has produced no real outcomes besides trillions of dollars in expenditure, countless arrests, and a broken prison system where addicts emerge with new and more violent drug connections. Rather than continue to fight a fruitless war against addicts doing drugs, mitigating the negative effects of drugs such as overdoses and transmission of HIV or hepatitis through harm reduction policy presents an empirical alternative to current policy.

Ultimately, stimulating and promoting recovery from drug dependence will improve overall health in the population, but the responsibility cannot be placed only on harm reduction programs. In order to support more recovery-oriented policies, it is imperative that systems be built inside communities in order to provide support and resources for families of drug addicts. Treatment systems, mutual aid networks, and family service organizations can support a larger public health agenda, helping connect those who are addicted and their families with the help they need.

Perhaps the most crucial public policy reform is a reduction of the stigma surrounding drugs and their users. Public campaigns can be particularly effective in this area, but they must be spearheaded with a policy directive aimed at classifying drug use as a health, not a criminal, problem. Increased engagement of society surrounding drugs and drug use can only be achieved if the current model of fear is dropped in favor of an educated and resilient population.

For people like Mike, the transition to a functional member of society is nearly impossible. Prior to his addiction, aspirations like financial security and a family life were within reach. Now, hope and recovery are distant dreams, since the system is not built to support them. Harm reduction programs like InSite, combined with policy directives that promote recovery and stigma reduction, will have substantial effects on the nation’s drug addiction problems. U.S. policies on drugs need to undergo a significant ideological and political change if they are serious about addressing the monumental problem of drugs and drug addiction.

Josh Sternberg

International Affairs ‘15

[1] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.

[2] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.

[3] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.

[4] The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population. Columbia University. New York, NY. February 2010.

[5] The British Columbia Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Findings from the Evaluation of Vancouver’s Pilot Medically Supervised Safer Injection Facility – Insite (UHRI Report). Urban Health Research Initiative. British Columbia. January 2010.

[6] The British Columbia Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Findings from the Evaluation of Vancouver’s Pilot Medically Supervised Safer Injection Facility – Insite (UHRI Report). Urban Health Research Initiative. British Columbia. January 2010.

[7] The British Columbia Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Findings from the Evaluation of Vancouver’s Pilot Medically Supervised Safer Injection Facility – Insite (UHRI Report). Urban Health Research Initiative. British Columbia. January 2010.

[8] http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/04-01_rep_mdtreatmentorincarceration_ac-dp.pdf

[9] http://www.stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/paradox/htele.html

[10] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/fy_2014_drug_control_budget_highlights_3.pdf

[11] http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/04-01_rep_mdtreatmentorincarceration_ac-dp.pdf