On Sunday, May 6th, François Hollande of the French Socialist Party defeated his opponent, Nicholas Sarkozy, with 51.6% of the popular vote. Tough economic times and recent “terrorist” attacks in Toulouse were the foremost discussions during the 2012 electoral campaign. François Hollande, the first Socialist president in the nearly two decades since François Mitterrand, benefited from Nicholas Sarkozy’s unpopularity and unimpressive five-year mandate to achieve the French presidency.

As an 18 year resident of Bordeaux, France, Hollande’s victory displeased me and reinforced my concern for France’s future economic prosperity. France is the second-largest economy in the euro zone (after Germany), yet it has failed over the past several years to generate enough wealth to fund its expansive social services system, benefits, and protections. These safety nets account for 56% of French GDP.

If this economic failure is improperly addressed, the erosion of French competitiveness, its incredible deficit, and the imminent failure of its social system could place France at the epicenter of the next Eurozone shock.

If Francois Hollande were to implement his proposed 75% tax rate, it would strongly deter international businesses to consider expanding in French markets because it means that taxpayers earning over €1 million ($1.35 million) would be required to pay three-fourths to the state. François Baroin, Mr Sarkozy’s Finance Minister, accused Mr. Hollande of, “inventing a new tax every week without ever proposing the smallest saving.” Many other Union for a Popular Movement (or UMP) politicians, like Alain Juppé, have denounced the proposed tax bracket and categorized it as “fiscal confiscation” or a “childish anti-rich precipitation and improvisation that is quite worrying,” while Mr. Hollande would like to consider it a “symbolic measure.”

France’s mandatory 35-hour workweek has tarnished the country’s economic image for years, and this change would only worsen the situation. The idea, “You know you’ve made it when you can ear money and not work,” cannot truly apply in France. Additionally, Hollande’s overall tax policy would discourage aspiring entrepreneurs and encourage the wealthy to move somewhere else, such as the United Kingdom, where the top tax rate was reduced from fifty to forty-five percent.

The French are consistently the most skeptical of capitalism: only 31% of the French population agrees that the free-market economy is the best system available, according to a poll by Globescan. Given this, it is easy to understand why a candidate like Hollande, who focuses on tax increases (up to 75% for the wealthiest) as well as social services and the employment of social workers, would be favorable and appealing to the masses.

We, the French people, live in this profound contradiction: we enjoy the wealth and jobs that global companies have brought, but we denounce the system that created them. We would rather dream of an increasingly generous and idealistic system rather than face our real problems and implement unpopular reforms, as Germany has done.

Rather than confronting these attitudes and removing the French people from our comfort zone, both candidates spent the campaign focusing on petty differences and aggressively attacking each other. The final debate, which happened a day before the election, exemplified this chronic lack of substantive discourse. Within the first hour, Sarkozy called his opponent “irresponsible” and accused him of lying, while Hollande accused his of “protecting the privileged” and creating “injustice and inequalities.” Both candidates engaged in a disorganized and ruthless discussion, which barely addressed fundamental questions.

Most aspiring Socialist candidates such as Mr. Hollande have been criticized for being too inexperienced to face tough economic problems. According to the initial ratings, Dominique Strauss-Khan, former Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, was the most favorable candidate to lead the Socialist Party for the 2012 election due to extensive previous experience. However, his embarrassing involvement in a sex scandal in a Manhattan hotel ruined his credibility and subsequently his chance of winning the 2012 election. As the last of the qualified Socialist politicians, his downfall extinguished my diminishing faith in French Socialist representatives.

Mr. Sarkozy would probably not have been a better candidate, but at least he has experience and an economic background that could have equipped him to make more comprehensive decisions. He successfully handled the financial crisis in 2008 as chairman of the European Union, was elected Minister for the Budget and Prime Minister’s spokesman in 1993, and conducted the tough but necessary first intervention in Libya in 2011 by sending troops to fight brutal leader Muammar Gaddafi. However, his desire for fame and taste for luxury displeased the French people, their President’s lifestyle seemed out of touch. Quickly, an anti-Sarkozy movement swept across the country, and a “normal” citizen emerged in France’s top political post.

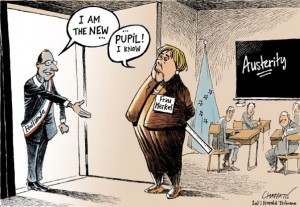

If François Hollande wants to successfully prove that he can rescue France’s economy, he will have to convince the French people of difficult truths and implement unpopular reforms, as Germany did. Hollande will also need to focus on both growth and austerity, and prove to the public that his inexperience will not prevent him from making tough decisions.

As Charles de Gaulle once said, “Les Français, ou qu’ils le cherchent, ont besoin de merveilleux” (The French, no matter where they seek, need the best) but I am afraid that this President will instead be a catastrophe if he pursues his theoretically wonderful but unrealistic and ultimately damaging reforms.

Pierre Bousquet

Business Administration 2014