Widely known throughout the world as one of the 20th century’s most impactful examples of family planning policy, China’s One-Child Policy (OCP) has caused serious social and ethical problems that have resulted in enormous changes in family dynamics, gender roles and demographics with Chinese society. Referred to as “the most massive human rights violation on the world today” by United States Representative Chris Smith, the OCP has been a source of great international debate throughout the decades.[i] Actions by the Chinese government, including its willingness to apply repressive means in order to achieve desired goals of central family planning within the People’s Republic, has alienated many in the international community and contributed to the governments already shaky human-rights record.

Imposed for all first-born children in 1979 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the OCP imposed a strict one-child per family restriction that accomplishes many goals of a rapidly expanding China. The policy was not only adopted to reduce skyrocketing fertility rates, but also to limit demand for natural resources. Like Chinese Communist Party (CCP) founder and dictator Mao Zedong, Chinese policy makers have sought to reduce unemployment caused by a surplus of labor.[ii] However, the applicability of the policy is limited as it only directly affects the urban Han population and only marginally affects the geographically isolated and ethnically distinct rural families. The labor-intensive work of the countryside on farms permits rural couples to have a second child if their first suffers from physical disability, mental retardation, or mental illness.[iii] Although the consequences of the OCP are not experienced uniformly throughout all of China, they have already been felt and will only worsen as time reveals new implications.

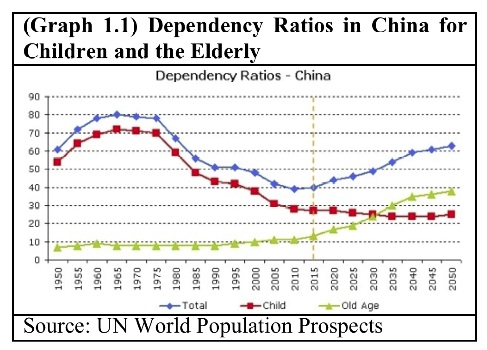

As a result of the OCP, each Chinese family faces new previously non-existent problems that need to be considered. Lifestyle and culture in China has, for thousands of years, revolved around Confucianism and its expectations for proper family behavior.iv Although many traditions remain, the OCP has posed new challenges to the way families interact and will continue to work together in the coming decades. The first such challenge, nicknamed the ‘little emperor syndrome’, reflects a growing phenomenon that has alarmed Chinese academics, media outlets, and foreign critics alike. The xiao huangdi, or ‘little emperors’ are only-children who are spoiled and pampered throughout their youth and therefore lack adaptive and self-disciplinary abilities as adults. As a result of the policy, China’s urban population is now earning greater per capita incomes, and children of the OCP era are receiving tremendous amounts of attention from their parents. After years of intensive focus on the maximizing of education and intellectual success, Chinese parents expect their children to show results in the classroom. It seems only natural to the Chinese that ‘little emperors’ should excel in essentially all aspects of life as pressure is placed on them to succeed and achieve in a competitive atmosphere during their childhood, rather than adolescence. Adults hope their extensive spoiling will pay off in the future, both for the success of their child and for themselves as they enter into their elder years.[iv] Another concern is what is known as the ‘4-2-1 Problem’. While historically, multiple children have shared the responsibility of caring for elderly family members, it is now up to a single individual to financially support his/her parents and grandparents. This inverted pyramid illustrates the name of the problem, with one individual balancing the financial burden of potentially six people upon his or her shoulders. With much larger, multi-children generations reaching their elderly dependent years, an inverse trend is occurring with the shrinking number of young adults in their prime working years.[v] According to the United Nations (UN) World Population Prospects, projections indicate the percentage of the Chinese population falling within the age range of 15-24 will drop from 18 in 1995 to just over 10 by 2040.[vi] This trend of fewer young dependents is illustrated in Graph 1.1.

As the first generation of only-children are now entering adulthood, the traditional practice of caring for the elderly is proving to be an enormous challenge. The future will see a rise in the number of dependent elderly community members and the test of the Chinese state-welfare and pension systems. The UN World Population Prospect studies from 2009 reveal a rise in the percentage of elderly dependent citizens as part of the entire population from roughly 10% between the 1980’s and 1990’s to about 60% in 2050.[vii] This data showing an aging dependent population is also shown in Graph 1.1.

An explosion in population growth in the latter half of the 20th century brought the issue of Chinese overpopulation to the forefront of international debates. In reaction to the growing concern that the abundance of Chinese people would eventually surpass the capacity and resources of their homeland to provide for them, the CCP was forced to react. In an economy not nearly as industrially advanced as today, the growing scarcity of resources were perceived as posing threats to the stability of the CCP regime. In response the Chinese government passed OCP which enacted strict regulations on family size. [viii]

National population control policies are not without precedent; many countries today experience population decline, therefore making concerns such as the ‘4-2-1 Problem’ a possible reality. Other countries throughout the world enact policies encouraging population growth that a very different from the OCP. These places do not witness such extreme population density and resource concern and as such encourage larger families. Significant monetary supplements are offered in Russia, equivalent to $9,200 in Rubles, for every woman with a second child.[ix] Similar incentives for larger families are currently being funded in Australia of $5,000 bonuses and full childcare coverage.[x] Singapore perhaps differs the most from its Asian counterpart China in offering $18,000 for every third and fourth child each.[xi] These countries are determined to not encounter a massive dependent elderly age group that asks more from their governments than they can offer.

Perhaps the most alarming result of the OCP has been the reinforcement of a historic male preference in Chinese society. The belief that males are better suited to financially support families originates in the country’s historic past when men dominated agricultural life. This stems from the Confucian belief in the primacy of male offspring, and manifests itself today in China’s drastically uneven sex ratio.[xii] In comparison to the natural baseline of the male to female gender ratio, about 103:100, China’s mainland reached an imbalance of 117:100 in the year 2000.[xiii] The Chinese State Population & Family Planning Commission has projected that by the year 2020 there will be at least 24 million more men than women if the current trends continue.[xiv] These disparities have far reaching implications for society as a whole including the increasing number of men unable to marry, rising kidnapping and trafficking rates, and a rise in the number of sex workers and associated spread of sexually transmitted diseases. However, it is not only the effects of this ratio disparity that reveals plenty of information about the negative effects of governmental population policy in China, but also the ways in which this disturbing tilt has come about. Although sex-selective abortion was officially banned in 1995, it is rarely enforced because of such a strong and pervasive desire for male children on the part of both society and the government. Such enormous importance is placed on the social necessity of male offspring that injustices occur daily with regard to the treatment of infant girls; abandonment, adoption, and neglect are common for newborn girls despite growing international concern and widespread criticism. Even infanticide and the intentionally less aggressive treatment of female infants in medical facilities occur on a regular basis. Largely out of fear, these processes arise from Chinese trepidation regarding the Population Control Officers (PCO) who operate under the control of the government and enforce the OCP. Harsh fines based on income levels, forced sterilizations, the use of intrauterine devices, dismissal from work, and the confiscation of belongings are consequences for violators of the OCP. In an attempt to conceal births from the PCO, those not officially sanctioned occur in private residences without trained personnel. [xv]

Even supranational bodies have had trouble ending the human rights violations that occur in China quite regularly. Though China is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), it has continually violated its provisions, with the most glaring example being the OCP.[xvi] This binding agreement, to which all UN members but Somalia and the US have agreed, is for a key tool in the global promotion of the rights of children. The UNCRC requires signatory states to act in the best interest of all children and outlines their natural rights, including the right to life.[xvii]

As analysts consider the current impact of the OCP in the 21st century world, much remains uncertain about the future. Zhao Bingli, vice minister of the State Family Planning Commission, claims that 300 million births have been prevented since the policy’s inception in 1979; though the accompanying drop in total fertility rates from 2.9 births per woman to 1.7 in the same time frame is considered a large achievement for the government.[xviii] However, international attention has been drawn to this so-called ‘achievement’ in a negative light with high-profile politicians such as former U.S. president George W. Bush accusing the policymakers of infringing upon human rights as specified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[xix]

Recent developments in China, including the blistering growth of its economy, have given the country a chance to radically transform itself however it sees fit. Politicians have adapted the ideologies of their 20th century leaders in order to better suit the China of today and the OCP has remained striking unchanged since first implemented. Without conforming to a changing society, the policy has furthered gender gaps that go far beyond the healthy ratios in place throughout most of the Western world, has created future dependency problems for urban families that fight to survive each day, and has led to disturbing human rights trends. Though the National Population and family Planning Commission officials have claimed that changes to the OCP to increase freedom will be considered in 2015, the future of the OCP remains masked behind a lack of transparency in the CCP.[xx]

[i] “UN must condemn China ‘one child’ policy: lawmaker.”dawn.com, Last modified March 8, 2011. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://www.dawn.com/2011/03/08/un-must-condemn-china-%E2%80%98one-child%E2%80%99-policy-lawmaker.html.

[ii] Huiting, Hu. “Family Planning Law and China’s Birth Control Situation.” china.org.cn, Last modified October 18, 2002. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://www.china.org.cn/english/2002/Oct/46138.htm.

[iii] “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years.” nejm.org, Last modified September 15, 2005. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMhpr051833.

iv Riegal, Jeffrey. “Confucius.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2011 Edition), Last modified July 3, 2002. Accessed September 29, 2011. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/confucius/.

[iv] Xueqin, Jiang. “Little Emperor Syndrome.” The Diplomat, Last modified July 9, 2011. Accessed September 30, 2011. http://the-diplomat.com/china-power/2011/07/09/little-emperor-syndrome/.

[v] “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years.” Last modified September 15, 2005.

[vi] “World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision.” un.org, Last modified February 24, 2005. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WPP2004/WPP2004_Volume3.htm.

[vii] “All Uphill From Here.” United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2009 Revision, February 24, 2010.

[viii] “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years.” Last modified September 15, 2005.

[ix] Gross, Daniel. “Children for Sale.” Slate, Last modified May 24, 2006. Accessed September 29, 2011. http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2006/05/children_for_sale.html

[x] Sayce, Chris. “Australia and its Population Control.” Money Morning Australia, Last modified April 6, 2010. Accessed September 29, 2011. http://www.moneymorning.com.au/20100406/australia-and-its-population-control.html.

[xi] Chivers, C. “Putin Urges Plan to Reverse Slide in the Birth Rate.” Money Morning Australia, Last modified May 11, 2006. Accessed September 29, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/11/world/europe/11russia.html.

[xii] Riegal, “Confucius”, Last modified July 3, 2002.

[xiii] “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years.” Last modified September 15, 2005.

[xiv] “China Faces 24M Bride Shortage by 2020.” CNN, Last modified January 11, 2010. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://articles.cnn.com/2010-01-11/world/china.bride.shortage_1_one-child-policy-female-fetuses-preference-for-male-heirs?_s=PM:WORLD.

[xv] “The Effect of China’s One-Child Family Policy after 25 Years.” Last modified September 15, 2005.

[xvi] “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” crin.org, Last modified November 20, 1989. Accessed September 25, 2011. http://www.crin.org/docs/resources/treaties/uncrc.asp

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Huiting, “Family Planning Law and China’s Birth Control Situation.” Last modified October 18, 2002.

[xix] Ertelt, Steven. “Biden Backtrack on China’s One-Child Policy Insufficient.”Life News, Last modified August 25, 2011. Accessed September 30, 2011. http://www.lifenews.com/2011/08/25/biden-backtrack-on-chinas-one-child-policy-insufficient/.

[xx] Huiting, “Family Planning Law and China’s Birth Control Situation.” Last modified October 18, 2002.